Amid the new development boom surrounding the revitalized High Line, the northeast corner of 11th Avenue and 23rd Street boasts a prime location, facing Chelsea Piers with views of the Hudson River. So it’s not surprising that an ambitious Israeli investor scooped up the site back in August 2012.

But seven years down the line, the site remains derelict. Passersby looking through the windows of the property can see the abandoned reception desk and lobby of a hostel that shut down in 2015. The building is still home to a handful of rent-stabilized tenants, paying an average rent of less than $300 a month.

Photos of the site at the corner of 11th Avenue and 23rd Street

“Our client is bleeding here, bleeding cash,” an attorney for the developer said in New York Supreme Court on August 1, before a judge agreed to extend proceedings one last time. “It’s five years in, millions of dollars spent and there’s still been nothing done as far as what’s the subject matter of this case.”

This five-year-old lawsuit is the latest in a long series of legal disputes surrounding the now defunct Chelsea Highline Hotel, as the would-be developer and the ex-FBI agent who owns the land underneath it have struggled to clean up a mess left behind by tenant-harassing strip club owners, and exacerbated by a group of savvy taxi drivers.

“A beautiful corner”

Photo of the Terminal Hotel in the early 2000s. (Credit: NYC Department of City Planning)

The four-story SRO building at 565 West 23rd Street (or 184 11th Avenue) has had a long, colorful history since it was built as the Terminal Hotel in 1860. It became a rent-stabilized hotel in the 1980s amid the city’s worsening homelessness crisis, and in addition to a rotating cast of bars and strip clubs on the ground floor, portions of the upper floors were once home to a S&M club and gay nightclub.

Things began to change in 2005 with the creation of the Special West Chelsea District, setting off a rush of new residential development in the area. Just north of the hotel, Annabelle Selldorf’s 200 11th Avenue began construction in 2007. To the east, West 23rd Street saw a flurry of projects pop up in anticipation of the High Line’s opening.

In 2007, MJG Holdings LLC picked up the ground lease on the hotel and the adjacent lot, with plans for another adult establishment on the premises — and much more besides.

“We’re gonna create a beautiful corner,” developer Jeffrey Wasserman told Curbed at a community board meeting in 2008, while applying for the property’s cabaret license. “This isn’t just a strip club. We want to put in a 15-story hotel, like Ian Schrager-style, with a beautiful view of Jersey.”

MJG subleased the adjacent lot to hotelier Richard Born, but the 15-story hotel encountered a legal obstacle. Because West Chelsea had been designated an “anti-harassment area,” and because the building was already subject to SRO law, the developers needed a Certificate of No Harassment (CONH) to proceed — and well, there had been a bit of harassment.

In 2009, an administrative law judge denied the developers’ CONH application due to “numerous acts of harassment,” including “verbal abuse and threats by management employees, posting of a humiliating sign, displays of violence, denying a tenant entry to his room, refusal to abate noise from hallway doors, and denying entry to a SRO tenant representative.”

Unable to proceed with their plans, the developers eventually transferred the leasehold to SkyBox/Chelsea LLC, a partnership led by Israeli financier Jonathan Leitersdorf. But the CONH decision would continue to haunt the property.

A very simple man

Jonathan Leitersdorf and a rendering of the SkyBox project (Credit: Getty Images and 6sqft)

Leitersdorf was no novice when it came to New York City real estate. In fact, he had co-founded development firm Savanna with managing partner Chris Schlank, whom he met at Columbia University in 1991.

“The first day of the program, I met the guy I started the business with, Jonathan Leitersdorf,” Schlank told TRD in 2014. “He had a lot of money and didn’t really want to work that hard. I had no money and wanted to work.”

And Leitersdorf really did have “a lot of money.” His grandfather Moshe Mayer was once Israel’s richest man, and built the country’s first skyscraper in Tel Aviv, the Shalom Meir Tower — whose top floors Leitersdorf later converted into a duplex penthouse for himself. Jonathan’s father, Thomas Leitersdorf, was the master planner for the country’s first major West Bank settlement at Maale Adumim.

In 1996, while still with Savanna, Leitersdorf began work on what would be his crowning achievement in New York City to date — the Dandy, a 10-story converted loft building at 704 Broadway, topped by a triplex penthouse and rooftop pool.

The penthouse, known as “Sky Studios,” served as Leitersdorf’s residence as well as a high-society party venue, hosting Jerry Seinfeld’s wedding and a birthday party for Chelsea Clinton. Leitersdorf sold the triplex to billionaire Ronald Burkle for $18 million in 2007.

Leitersdorf’s plans for SkyBox were even grander, with a five-story penthouse — again for his personal use — and an art museum and private gallery on the ground floor stocked with works by the likes of Picasso and Kandinsky.

Around the same time that these plans were revealed, Leitersdorf was the subject of a glowing profile by Wall Street Journal, detailing his luxury homes in New York, Geneva and Tel Aviv.

“I am a very simple man,” he told the Journal. “I fly commercially instead of on private planes and drive a Mercedes, not a Ferrari.”

Representatives for Leitersdorf and SkyBox did not respond to requests for comment.

“A self-styled crusader”

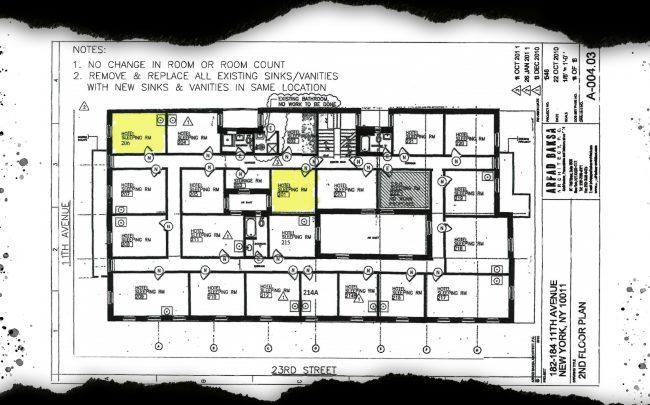

Floor plans included in the lawsuit show how new tenants (highlighted) would allegedly interfere with the project. (Click to enlarge)

Another key piece of the SkyBox project would be the renovation of the hotel into permanently affordable housing — a “Cure for Harassment” required to make up for the 2009 decision. But some tenants refused to play ball — and even brought new tenants in to complicate matters.

Joe Stevens, a taxi driver who had been living at the hotel since 1996, was one of the key witnesses in the harassment proceedings against the previous developers, and he didn’t seem to like Leitersdorf and partners any better.

“A self-styled crusader against the project,” Stevens “has made a name for himself by attracting individuals, new to this State (and sometimes the country) advising them to seek permanent residency at Chelsea Highline,” Skybox’s attorneys would later allege in a lawsuit.

Oltimdje Ouattara (Credit: Facebook)

Two of those individuals, Hamidou Guira and Oltimdje Ouattara, made headlines in 2015 when they checked into the Chelsea Highline — operated by Jazz Hostels at the time — and then used an obscure SRO law to become permanent tenants. Court documents show that two other individuals also became permanent tenants of the hostel in 2015, but received less publicity.

This is precisely when things took a turn for the bizarre. The hostel stopped operations on August 7 — just four days after Ouattara checked in — and Skybox sued Ouattara, the Division of Homes and Community Renewal, and the City a month later, arguing that the city’s rent-stabilization laws were unconstitutional.

“It is unfathomable that such an outcome was intended by the drafters of these various sections of the Code,” the lawsuit stated, adding that the application of these laws would “deprive Plaintiffs of the ability to cure the harassment issued against this property since 2009, and prevent Plaintiffs from complying with the zoning laws.”

SkyBox dropped the lawsuit two months later, but the project’s legal problems were far from over.

Representatives for Jazz Hostels did not respond to a request for comment. Oltimdje Ouattara declined to comment, and Joe Stevens could not be reached.

“My pride and joy”

Even before Stevens’ new friends began moving into the Chelsea Highline, SkyBox had already found itself on shaky ground — because of the ground underneath the hotel.

The property’s fee interest was owned by Gurdayal Kohly, an immigrant from the Punjab who had come to the United States as a student decades ago. Property records show that Kohly acquired the property in 1979, when land on the far West Side was still cheap.

“The Property is the only investment property I own and, as such (and as it is my main source of income), it is my pride and joy,” Kohly said in an affidavit. “Due to my limited means, net-leasing is the only viable option for me to be able to realize any profit from the Property.”

Kohly also noted that he had served as an FBI agent for nearly 30 years. “My proudest moments came after the September 11, 2001 attacks, when the FBI was able to utilize my South Asian background and language skills to bolster our nation’s security,” he said. He retired from the Bureau in 2006.

By early 2015, SkyBox’s relationship with Kohly had soured due to rent disputes and a backlog of uncleared building violations, many left behind by previous ground lessees. In June, SkyBox (via an entity named Audthan LLC, the actual lessee) sued the landlord, alleging that he was improperly trying to terminate the lease after having “second thoughts.”

New rent-stabilized tenants began moving in soon after, and things ground to a halt. Kohly’s lawyers seized on the new tenants as further proof of SkyBox’s mismanagement of the property, and argued that their presence would require a complete redesign of the project in order to satisfy the mandated affordable housing requirements.

“Owner is now faced with the likelihood that some portion of the low income cure space will have to be located in the market rent condominium unit that was to revert to Owner after execution of the Lease, which would not only be unfair to Owner but would necessitate a complete redesign of the Building layouts,” another affidavit states.

Kohly has refused to sign a “Cure Agreement” with HPD that would allow the project to move forward, and the court denied a motion from SkyBox to force him to do so, noting that “a delay in the project’s progress does not equate to its failure.” To date, no permits have been issued.

“While I am not the ‘major player’ that Mr. Leitersdorf is, I nevertheless am guaranteed certain legal and ownership rights with respect to the property, which rights I will continue to press to the fullest extent of the law,” Kohly said in an affidavit.

“The Property will be my main gift to my family after I pass, and I insist on doing business no other way.”

“It’s not about affordable housing”

Four years later, after further disputes involving 60,000 pages of discovery documents, mismanagement of security deposits, and a separate legal proceeding in New Jersey, the Chelsea Highline site has remained in limbo.

The Property will be my main gift to my family after I pass, and I insist on doing business no other way. – Gurdayal Kohly

But despite all of this back-and-forth over the technicalities of building violations and permanent tenants, the real heart of the dispute appears to be rather simple — it’s about money.

“Your client has a sweetheart deal. That’s the reason we’re in this litigation,” New York Supreme Court Justice Robert Reed told Skybox’s attorney in court on August 1, responding to a comment about the financial toll the lawsuit was taking on the developer.

“I’m not concerned about your client’s suffering. The reason we’re here is because the landlord believes that he has gotten snookered, all right? That’s why we’re here. So both sides bear responsibility for the financial state that they find themselves in.”

“It’s not about affordable housing, it’s about someone trying to make a good land deal on valuable land,” he added.

Bradley Silverbush of Rosenberg & Estis P.C., whom Kohly retained in July to replace his prior attorney, says his client executed the ground lease for a price that was far below market rates. “Quite frankly, he was taken advantage of,” he said.

As the court’s patience with this case has run thin, a breakthrough may finally be on the horizon. On August 1, Reed ordered that depositions of SkyBox’s principals be completed within 45 days, after which summary judgement is to be made within another 60 days.

“This case ultimately, is a case that needs to be resolved by some level of the commercial mediation. There’s a number that will satisfy the parties,” the judge said.

“Someone needs a ransom to be paid.”