Housing experts say a proposed bill to turn tenants into building owners won’t work without funding to back it up.

The state bill would grant tenants the first opportunity to buy their building should it come up for sale. If they cannot come to terms with the owner on a price, it would be determined by an independent appraiser based on the market, according to those crafting the legislation.

But giving tenants the inside track to buy their buildings would not guarantee their capacity to do so unless a subsidy were to accompany the program, according to affordable housing developers and advocates for the business community.

Simply removing landlords from the equation would do little to provide affordable housing, they say. And landlords add that managing buildings is not an easy task.

“It’s a natural response to say, ‘If no one wants to own this, there has to be a way for tenants to own and maintain buildings,’” said Kathryn Wylde, president and CEO of the business group Partnership for New York City, referring rent-stabilized buildings’ profit potential being shrunk by last year’s rent law. “Unfortunately, without a financing program to go with it, it’s unrealistic.”

Read more

Affordable housing developers point out that the proposal would not make housing less expensive. Tenant advocates and proponents of nonprofit affordable housing development agree that without public subsidy, such a program would not help those without the financial means to purchase their buildings, and is not a panacea for the affordability crisis.

“It’s not an efficient way to give people affordable housing who need it,” said David Schwartz, principal of affordable housing firm Slate Property Group. “We have to figure out a way for progressives to have dialogue with everyone involved in affordable housing — and you can’t vilify people for having dialogue.”

Chris Athineos, who owns nine buildings with 150 apartments in Bay Ridge, is among the New York City property owners looking to shed at least some rent-regulated assets. Athineos, whose decades of building-management experience is not easy to come by, cautioned tenants who would dive into ownership without expertise or institutional support.

“If a tenant were to buy a building, it would be good to get experience by working for a building owner or management company,” Athineos said. “You have to know so much, not just about finance and underwriting, but about plumbing and electrical. It’s not just collecting rent.”

Citing one common but little-known hazard facing building owners, he said, “An oil truck might short you because he filled up his girlfriend’s oil tank on his way to your delivery. These are things you learn through experience.”

The most ambitious example of tenants attempting to buy their buildings was a $4.5 billion offer by Stuyvesant Town residents in 2006 to owner MetLife. They lost out to investors led by Tishman Speyer who ultimately paid $900 million more in an ill-fated strategy to turn over units and raise rents. The buyers defaulted on their loan and lost the property.

Dan Garodnick, a former New York City council member and longtime Stuyvesant Town resident who led tenants’ 2006 negotiations with MetLife, said a mandate to give tenants special consideration would have “added leverage to the tenants’ position … and created an actual obligation to work with the tenants.”

Had their offer been accepted, “there would have been a lot less turmoil,” Garodnick said. “People would not have been pursued by their new landlord, and it would have meant both stability and long-term affordability for the community.”

It is impossible to know how a tenant takeover of Stuyvesant Town would have turned out, but it would have meant $900 million less for Met Life. That is one reason the pending bill is likely to be opposed by landlords.

But the multifamily market has changed drastically since 2006, curtailing aggressive bidding like that of Tishman Speyer in 2006. Reforms passed last year eliminated nearly all of the rent-raising techniques that the company planned to use. As a result, prices have dropped and some landlords have indicated that they will halt renovations, keep units vacant or even flee the New York City market all together.

The bill, which is expected to be introduced soon by Sen. Zellnor Myrie, is being modeled on laws in a handful of other places. Those measures finance conversions to limited-equity co-ops with revenue from mortgage- and deed-recording taxes.

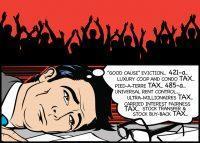

Myrie has also proposed legislation to eliminate the Affordable New York tax exemption for new apartment construction and has joined tenant advocacy groups to push for more taxes on the wealthy.