Neighbors, landlords and a developer on a Tribeca block have for four years been at war with each other over who can park in a private alleyway called Franklin Place.

And more than once, city agencies appear to have taken a side in their protracted legal battle.

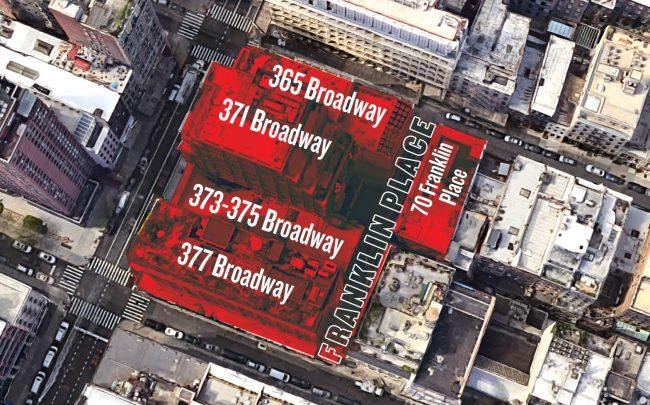

Five buildings — 365 Broadway, 371 Broadway, 373-75 Broadway, 377 Broadway and 70 Franklin Place — each own part of the alley. Cross-easements have for decades allowed the neighbors to cross each other’s sections of it.

The five buildings that own a part of Franklin Place (Credit: Google Maps)

It worked pretty well until 2016, when Isaac Tshuva’s Elad Group finished a condo project at 5 Franklin Place and its unit owners moved in. Apparently the traffic at their front steps, which faced the alleyway, was worse than they expected.

Coburn Packard

In court documents, the condo board — led by Coburn Packard, the co-head of real estate for Michael Dell’s family office MSD Capital — accused Elad Group of “egregious” fraud in how the alley was represented to buyers. Their property values were hurt by the traffic, they said; board member Shazma Alibhai said she and her children have nearly been hit by vehicles maneuvering around cars parked in the alley.

The condo residents also claimed emergency vehicles might not be able to pull up to their front doors.

But the board and Elad are now working in collaboration, sources say, as the board tries to get Franklin Place declared a public street with no parking allowed. It has hired lawyers and lobbyists to make that case to the attorney general’s office, the Department of Transportation and the Fire Department, among others.

“We have been working endlessly, and at significant cost to our building, to defend ourselves and persuade the city to prioritize safety over all else,” the board said in a statement. “The city can solve this problem if it chooses to.”

Robert Goldstein

Meanwhile, neighboring building owners, including Macbeth theater performance “Sleep No More” producer Arthur Karpati and Robert Goldstein, managing partner of law firm Borah Goldstein, argue that their property rights would be violated if parking were banned. They accuse the city agencies of unfairly intervening on behalf of the condo.

“Should the condo prevail, this will set a terrible precedent,” said Michael Contos, the attorney representing the owners of 373-75 Broadway. “It would say if you are a developer and you come in to develop a site, you could basically do whatever you want to your neighbors.”

The condo board hired lobbyist Capalino and Company and has spent nearly $160,000 in the past three years lobbying the city on the matter and the Elad Group has spent $480,000 over four years, according to lobbying records. Contos said the neighboring buildings are shelling out significant sums on legal fees.

The condo board’s effort seemed to pay off in November when the Fire Department sent a letter to the neighboring building owners saying it had made a “preliminary determination” that Franklin Place was a fire apparatus access road, which would ban parking in the alley.

However, to qualify, according to the Fire Code, the alley would have to support a load of at least 80,000 pounds and be 34 feet wide. Contos said Franklin Place is, at its widest, only 25 feet across.

5 Franklin Place

The FDNY’s letter acknowledged that there is a void under the street and asked the neighbors to allow an engineer hired by 5 Franklin Place to determine what weight it could support.

But Robert Moezinia, who owns 365 Broadway, one of the buildings beside the condo, had commissioned such a study in 2012 at the request of the Department of Buildings. It found the road would be safe for local deliveries and parking, but not necessarily for “heavy vehicles” or cranes.

Moezinia called the FDNY’s November correspondence a joke. The department did not respond to questions about its letter or involvement beyond commenting through a spokesman that “public safety is the primary concern.”

The department’s action was not the first time a city agency has appeared to go to bat for the condo project.

In June 2017, the Department of Transportation installed “no standing” signs in the privately owned alley. Correspondence obtained by The Real Deal shows the signs stemmed from a request by the condo developer — and that an agency official, Luis Sanchez, expected cooperation on unrelated bus-stop infrastructure in return.

“[Luis] Sanchez is very upset because he accommodated our request for signage on Franklin Place — and feels we haven’t moved on DOT’s concerns regarding the bus bulb on Broadway,” Omar Alvarellos of Kasirer, Elad’s lobbyist, wrote to the developer’s CEO, Yoel Shargian. A bus bulb is a curb extension that allows buses to pick up and drop off passengers without pulling over.

Yoel Shargian

“I am concerned that our other projects will be more carefully scrutinized by DOT (including 505 West 43 Street) unless we make progress on this issue,” added Alvarellos, who spent eight years as the Giuliani administration’s City Hall liaison to numerous agencies.

Later, Elad’s Shargian said in a statement that the bus bulb was a requirement for the condo project and was “completely unrelated to the alley access issue.” A DOT spokesperson declined to elaborate on the exchange but denied there was any agreement with the developer over the bus amenity.

In the summer of 2017 the condo board began pushing the DOT to designate the alley a public street. That fall, the neighbors sued the condo, developer and city over the no-standing signs. DOT removed the signage in January 2018 and was dismissed from the case, which is still pending.

“If we had not put up a big fight, those ‘no standing’ signs would still be there, I suspect,” Contos said.

But Moezinia, the building owner, said city agencies should steer clear of the alley fight.

“For the city to get involved in this, this is wrong,” he said. “It’s not the right way of doing things.”