Shareholders are sending Vector Group’s C-suite a message — and it’s aimed at their wallets.

On Thursday, the publicly traded parent of brokerage Douglas Elliman and new development firm New Valley asked its investors to bless the pay packages its top five executives received last year.

And for the second year in a row, shareholders balked.

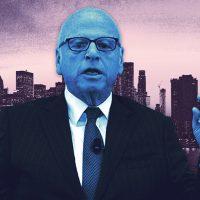

A majority at Vector’s annual stockholder meeting rejected executives’ 2019 compensation, including $11.7 million showered on Elliman chairman Howard Lorber, Vector’s president and CEO. Four other executives earned a total of $7.4 million.

By comparison, Steve Roth, whose Vornado Realty Trust has a market capitalization nearly four times that of Vector’s, received compensation of $11.1 million in 2019, while Brett White, CEO of Cushman & Wakefield, which is worth 29 percent more, had a $9.3 million package.

Ryan Schneider, Lorber’s counterpart at Realogy Holding, whose market cap is 60 percent less, collected $8.8 million.

Read more

Kenneth Steiner, a retail investor who has owned stock in Vector for a decade, calls Vector’s pay “excessive,” particularly Lorber’s. He could not recall in his 25 years as a corporate activist seeing a majority of investors oppose compensation packages in two consecutive years.

“It’s a strong rejection of the compensation packages and a strong rejection of the board of directors,” Steiner said.

Steiner noted that such advisory votes on pay typically receive 95 percent to 97 percent approval. A prolific filer of shareholder proposals, Steiner has waged hundreds of campaigns on PepsiCo, Oracle, Exxon Mobil and other companies.

Last year, 50 percent of Vector’s investors voted against its pay proposal, while 49 percent approved it and 1 percent abstained. This year’s vote breakdown has yet to be publicly recorded.

Of thousands of public companies that conduct these votes, less than 1 percent fail to get majority approval in any given year, noted Stewart Reifler, a lawyer specializing in executive pay.

“If a company cannot get an 85 percent or above approval vote on ‘say on pay,’ then that’s a strong indicator the company has a fever,” Reifler said. “If a company’s ‘say on pay’ vote is below 50 percent, then, to paraphrase the Music Man, ya got some serious trouble in River City.”

“Say on pay” became a hallmark of annual shareholder meetings as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. While non-binding, the vote can pressure a company into reducing its largesse to executives.

Reifler described the annual rite as “like taking the temperature” of investor sentiment.

“Typically, when things are going great at a company, ‘say on pay’ votes are never an issue,” he explained. “However, when the activists have the battering ram at the castle door and when the company is poorly performing, it is then when we see shareholder anger at executive compensation and a corresponding negative say-on-pay vote.”

In Vector’s first-quarter earnings, its real estate businesses reported a net loss of $54.4 million, which was six times the size of its first-quarter loss a year ago. Lorber attributed the result to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Vector’s overall performance last year was flat, though its results in the real estate market were erratic from quarter to quarter. Starting this year, the company halved its quarterly dividend and eliminated its annual dividend.

Steiner said he hopes shareholders’ vote on pay will prompt Vector’s board of directors to act. “This is a strong signal to them that they’re not doing their job properly,” he said.

The board is chaired by Bennett LeBow, a financier who previously controlled one of Vector’s tobacco businesses, Liggett Group. Other directors include Lorber; Paul Carlucci, former advertising executive and publisher of the New York Post; Barry Watkins of communication firm Clairvoyant Media Strategies and advisor to Madison Square Garden Company; and Stanley Arkin, founding partner of his eponymous law firm and a private intelligence agency. Vector declined to comment on Steiner’s statements.

Though Steiner is sounding the alarm loudest, the company’s big institutional investors seem to be making noise behind the scenes. They include asset manager BlackRock, Vector’s largest shareholder with 12 percent of its common stock; investment giant Vanguard Group; and hedge fund Renaissance Technologies.

Vector’s board has tried to respond to investor concern. Before last year’s annual meeting, Vector informed stockholders it had gathered feedback from institutional investors and would review its executive compensation program. The results were to be published ahead of the 2020 stockholder meeting and recommended changes to executive pay would be made that year.

The review is still ongoing, but preliminary results were reported in Vector’s 2020 proxy statement.

The company justified its compensation by noting the challenge for determining appropriate pay given Vector’s disparate holdings — tobacco companies as well as real estate.

Though Vector reported that no “specific changes” have been made, it requested conversations with every institution that owned more than 2 percent of its stock. Participating investors requested more transparency and supported Vector’s intent to link compensation to long-term performance.

Vector said it would “carefully consider” the feedback and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic as it firms up 2020 compensation. A spokesperson said it is in regular contact with institutional investors.

In response to the economic downturn, many real estate executives, including Vornado’s Roth and Cushman & Wakefield’s White, announced pay cuts, and some are taking zero salary. On average, most gave up about 20 percent of total compensation.

Reifler, the compensation attorney, noted that activist investors’ challenges to executive pay is not motivated by moral righteousness.

“The activists are there to make a buck, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” he said. “But let’s not be naïve and think they’re there for something else.”

Write to Erin Hudson at ekh@therealdeal.com