When protests in Los Angeles following George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police officers turned to vandalism, Koreatown was left untouched.

The lack of disruption during the weekend after Floyd’s death was notable. Koreatown has historically been a flashpoint for racial tension including during the 1992 L.A. riots when properties were set ablaze amid searing images of store owners waving guns.

The calm seemed another sign of Koreatown’s post-riot bloom, a recovery driven by Jamison Properties’ David Lee and other local real estate developers.

Koreatown is the most densely populated neighborhood in L.A., “A happy mix of flashing neon lights, nondescript office buildings that house innovative restaurants and dark nightclubs, and eclectic shops in old Art Deco buildings,” declared a Curbed LA story last year.

But Koreatown’s rise faces uncertainty. The coronavirus pandemic may decrease demand for vertical, urban living just as Koreatown fills up with cranes and scaffolds for high-rises.

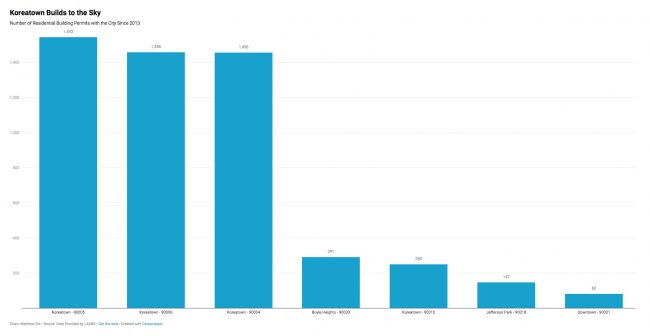

A data analysis by The Real Deal shows what the eye sees. In the 90005 Zip Code, a stretch that dips south and around Wilshire Boulevard in Koreatown, there is four times the number of apartment units that developers are constructing compared to the average L.A. County Zip Code.

Community activists fear Lee and other developers have built without regard to their mostly immigrant community. Real estate pros, meanwhile, fear the high-rises are no longer good business.

“Sure, there is a demand for housing, but the question is whether people can make the rents to cover the cost of building,” said Peter Tateishi, executive director, of California’s Association of General Contractors. “There is a concern, and we are not sure when this will catch up to us.”

Others say it is about to catch up.

“The current economic downturn is likely to be acutely felt in Koreatown,” said Eric Willett, a researcher at CBRE.

Jerry Brown, David Lee, and TOC

Koreatown is 2.9-square-miles with 118,000 people “sandwiched between downtown and Beverly Hills,” notes real estate attorney Doug Praw.

Korean immigrants entered the area in the late 1960s, and by 1980 Los Angeles County designated “Koreatown” as a neighborhood.

During the 1992 riots, some rioters did target Koreatown because Korean immigrants had clashed with Black residents. But the communities destroyed by the riots were in South L.A. like Compton and Watts. Koreatown was merely damaged.

“The property damage wasn’t as bad in Koreatown,” said Edward Chang, author of “Korean Americans: A Concise History” and ethnic studies professor at UC Riverside. “They were able to relatively quickly rebuild and recover.”

One post-riot fallout, Chang said, is Korean immigrants invested more in Koreatown itself. That included Lee, a physician, who opened Jamison Services in 1997.

The hard-charging Lee – who once at a community meeting threatened development foes that he would come back with an assault rifle – first developed office high-rises. But by the late 2000s recession Lee started moving away from just office buildings and poured money into multifamily properties.

Lee’s aggressiveness has stirred ambivalence among a Koreatown community composed of different generations of Korean immigrants, and also 50 percent Latinx.

“A lot of his projects don’t seem to be keeping equity and community at heart,” said Alexandra Suh, executive director at the Korean Immigrant Workers Alliance. “I think because it is a Korean-owned company, people seem to think, ‘Oh, it’s better to have one of our own.’”

Suh wonders if Lee, who came over to Los Angeles from Korea as a teenager, has contributed to making the neighborhood no longer affordable for first-generation immigrants.

The average Koreatown apartment building on the Multiple Listings Service is a two-bedroom leasing at $3,247 a month.

Grace Yoo, former president of the Korean American Coalition who is running for Herb Wesson’s soon to be vacated City Council seat, voiced a similar concern.

“At times it feels like Jamison Properties owns more than half the large buildings in Koreatown,” Yoo said. “As a major stakeholder in the area, I would hope that Jamison would be more attentive and receptive to the requests of the local residents.”

A Jamison spokesperson declined to make Lee or other company officials available for an interview, including any changes in the company’s strategy. Jamison’s latest move is a $31 million sale of the Maya, a 70,000-square-foot apartment building on Kingsley Avenue in the heart of Koreatown, to Omninet Capital.

Regardless of his community perception, Lee’s headfirst dive into apartments had, up to the pandemic, seemed like a smart business strategy.

It came as elected officials like former Gov. Jerry Brown began planning housing policy around public transportation. Koreatown, home to two public transit lines and the Wilshire Boulevard rapid transit bus, was seen as where L.A is headed – more walkable, and less greenhouse gas emissions.

The Wilshire Vermont apartments at 3183 Wilshire Boulevard

“Koreatown was a big part of L.A. moving away from all the single-family homes,” Suh said.

One change was construction starting on an $8.2 billion expansion of the Purple Line, which now goes from downtown to Koreatown, with expansion to put the line through Beverly Hills.

Another was the quiet passage of a 2016 state referendum (voted on during the election that Americans elected Donald Trump and Californians legalized marijuana) that greenlighted the Transit Oriented Communities program, or TOC.

“Pre-pandemic, there was a very intense focus on Transit Oriented Communities,” said Praw, a lawyer at Holland & Knight.

Under the program, developers who build within half-a-mile of a metro stop or rapid transit bus line enjoy a major relaxation on how much they can build.

How major? If a developer promises to set aside 20 percent of their units to individuals making less than $54,250 a year or a family of four making less than $77,500 a year – what the federal government and L.A. County presently define as low-income – they can build 50 percent more. Set aside 25 percent of units for low-income housing, and developers can build 80 percent more.

Towers, towers everywhere

At least one data point, apartments listed on the Multiple Listings Service, confirms an increasing number of Koreatown apartments are coming to market – three times more in the Koreatown-dominated zip codes of 90005, 90010 and 90020 compared to other residential neighborhoods like Baldwin Hills.

There are more complete facts on the amount of apartment units planned for construction, under construction, and built and ready to lease.

Approved city building permits from 2013 on, comparing Koreatown to zip codes with similar median income. (CLICK TO EXPAND)

The 90005 zip along Wilshire Boulevard has 4,791 units either being built, planned to be built, or put on the market in the zip code, according to mortgage broker Berkadia.

By comparison, the average L.A. County zip code has 1,375 apartment units in the pipeline.

The only zip with more units being built than 90005 is 90028, downtown’s South Park neighborhood where the biggest towers on the Pacific coast are being built, such as Greenland’s 1.679-unit Metropolis.

CBRE figures show another way of looking at the development boom: For every five apartment units in Koreatown there is one “under construction and likely to deliver in the next several years,” according to Willett of the commercial brokerage.

Willett noted a pandemic is not the best time for the “new developments to deliver.”

Many of the developing towers are Jamison’s, like a 510,000-square-feet complex by the Wilshire/Normandie Avenue Purple Line stop set to contain 428 residential units.

3545 Wilshire Boulevard and the proposed project for the space (Credit: Google Maps and BuzzBuzzHomes)

But other major league developers have started to get in on the action.

Hankey Capital is teaming with Jamison on a 25-story, 644-apartment building on Wilshire just east of the Wilshire and Vermont Avenue Purple Line.

Dallas development titan Trammell Crow is building office space and a new headquarters for the county’s Department of Mental Health one block north of Wilshire and Vermont avenues.

And Hollywood’s Harridge Development Group has planned a 35-story, 555-apartment tower a block east of Wilshire/Vermont.

Before coronavirus, Koreatown development was moving so fast that there were not enough construction workers, bragged David Lee’s son Garrett Lee in a Los Angeles Business Journal interview in September.

“There’s only so many construction workers, so many architects and engineers,” said Garrett Lee, the president of Jamison. “One of the challenges is being able to build a project on the schedule you want. We could build even more if there was a bigger labor pool out there.”

A New Residential Marketplace

Even before coronavirus hit California, there was one curious wrinkle in Koreatown’s success story.

Two planned hotel high-rises, including one by Jamison, were being changed at the 11th hour into apartments.

A third hotel by Century City developer Urban Commons is still planned the company says, but the company faces a slew of financial problems including a default on a Bank of America loan.

“Hotel development has pretty much come to a grinding halt,” admitted Alan Reay, president of hotel broker Atlas Hospitality Group. “Developers and operators are pivoting to apartments.”

The big question, of course, is how many apartments can sell and at what price.

A required number of units are set aside for affordable housing, but the vast majority of new units the last five to 10 years were priced to compete with higher-end neighborhoods like downtown and Hollywood, said Chang, the ethnic studies professor.

While Chang frets about where Koreatown is headed, industry representatives fear the coronavirus has disrupted the transition to wealthier renters.

L.A. Residential landlords like Neil Shekhter trumpet the coronavirus’s impact as helping the city long term, the idea being residents from New York and other dense cities will choose sprawl.

“The coronavirus created a whole new residential marketplace,” Shekhter said.

But that marketplace would benefit traditional single-family L.A. neighborhoods at Koreatown’s expense.

“Koreatown is a vertical neighborhood,” Praw said. “People are going into parking structures and traveling on an elevator, which is being second-guessed right now.”

One argument that Koreatown has not overbuilt is that whatever the neighborhood’s particulars there is still a region-wide housing shortage.

Don Favia, a Koreatown broker at Realty Investment Advisors, points to the state government’s Regional Housing Needs Assessment, which finds that, “Conservative estimates for Los Angeles alone run at 450,000 units of housing that need to be built by 2029.”

Community activists hope future projects include more affordable housing. But they voice a fear of oversaturation. One concern is parking. Despite proximity to public transportation, most residents and visitors of Koreatown drive.

“Parking is a topic of high emotions,” Suh, of the Worker’s Alliance said. “All the small malls and restaurants have gone to valet, and there’s no space to build more lots.”

Suh takes a long view of Koreatown’s identity as being a place of constant change, fluctuations that are extreme even by L.A. standards.

“Koreatown is one of the neighborhoods that has changed the most since the riots. It has not always been bad or good,” she said.

Where all sides agree – or at least want to agree upon – is that the pandemic will not throw the neighborhood’s next phase into too bad a direction.

“L.A. is still a net importer of people and Koreatown is a hot neighborhood,” Praw said. “Pandemic aside, I still believe in the Koreatown story.”