Commercial evictions could be on hold until at least May if Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s 2022 state budget proposal is enacted as-is.

The governor first proposed the ban, which would go into effect through new legislation, as part of his State of the State addresses earlier this month. The current eviction ban, which has been repeatedly extended since it was enacted last March, is set to expire at the end of January.

Much like New York’s recently passed blanket moratorium on residential evictions, the legislation would require commercial tenants to attest that they have experienced financial hardship by completing a form that can be returned to either the landlord or the court. The current rules limiting commercial evictions do not require a hardship declaration.

Commercial tenants with pending eviction proceedings could also avail themselves of the protections by proving they have not received federal, state or local aid as a result of the pandemic.

The protections would apply only to evictions for non-payment, not those arising from things like a lease expiration or a violation of lease terms. The protections would also not cancel rent owed.

Read more

Some industry insiders aren’t thrilled with Cuomo’s proposed legislation, although his version of the eviction ban is less broad than a measure proposed by the New York State Senate last week. That bill, sponsored by Nassau County Sen. Anna Kaplan, would ban all evictions — not just those for non-payment of rent — for businesses with 50 employees or fewer.

In a statement, James Whelan, president of the Real Estate Board of New York, said that the organization’s members have worked hard to keep tenants in their spaces, but emphasized the importance of making sure the legislation does not protect tenants whose ability to pay rent was not impacted due to Covid-19.

“If property owners do not receive rent from tenants who can afford it, it will become more difficult for them to use increasingly limited resources to help impacted tenants weather this crisis,” said Whelan.

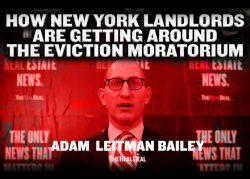

One point the two bills do have in common, according to Jeffrey Goldman, who heads the litigation department at Belkin Burden Goldman, is a disregard for the judiciary’s ability to determine whether tenants deserve protection. Hardship declarations do not have to be defended in court, and although lying on the form would amount to perjury, prosecuting commercial tenants for doing so is very unlikely, Goldman said.

“Taking away judicial discretion for the vast majority of cases in the city of New York tells you something about what the executive and legislative branches think of the judicial branch,” Goldman said. “It’s saying we can’t trust the judiciary to use discretion to determine whether or not there’s a hardship declaration.”

But others consider the new legislation to be a slight improvement for landlords. Alexander Tiktin, an attorney at Davidoff Hutcher & Citron, explained that the affidavits could be used as evidence in ongoing lawsuits seeking money judgments. For businesses that have gotten federal Covid relief funds, lying could be a dangerous gamble, since the Treasury Department discloses which companies have received $150,000 or more from the Paycheck Protection Program.

“New York is trying to balance the scales a bit and throw landlords a bone, without making it so obvious that they have a large reprisal from the tenant lobby,” said Tiktin.

The proposed budget may change before the Apr. 1 deadline as it is negotiated with the state legislature; the Senate, which has a veto-proof Democratic supermajority, may hold considerable sway over the final version. Both the Senate and Assembly will hold virtual hearings on the proposed budget, beginning next week.