UPDATED Tuesday August 3, 2021, 3:19 p.m.: Most teachers don’t spend their midsummer weekends on field trips, but Aicha Davis is no ordinary educator.

Based in Dallas, she is an elected member of the Texas State Board of Education, which monitors the activity of the state’s public school educators and oversees the Texas Permanent School Fund, a sovereign wealth fund with a nearly $50 billion endowment.

Last weekend, she traveled up to New York City — her first time visiting the Big Apple — to spend about three hours walking through Park Slope and meeting tenants in buildings owned by the fund’s controversial real estate investment partner, Greenbrook Partners, which has been emptying rental buildings throughout Park Slope to renovate them and lease the units at much higher prices.

It was a highly unusual move, so much so that Brad Lander, the local council member and soon-to-be comptroller who is trying to keep Greenbrook’s tenants in their homes, called it both a “moving” and “kind of crazy” development. He said Davis informed him two weeks ago that she was coming to the city and wanted to talk with the tenants, so he and his staff set up the visit.

Now, Davis says she’s on a mission to change Texas law regarding the strategies state-owned investment funds can pursue.

“My inspiration for coming was to see the truth about what was going on,” she said. “This is just not right.”

Last year, the Texas Permanent School Fund invested $100 million with London-based real estate investment firm NW1. At least $25 million was spent buying small, run-down multifamily properties in Brooklyn to fix and flip.

But NW1’s local partner, Greenbrook, which is handling the day-to-day execution of the strategy, has come under scrutiny for its conduct toward tenants during the pandemic. (Greenbrook’s Brooklyn portfolio is not exclusively funded by NW1 and the Permanent School Fund; Greenbrook has been buying up buildings in the borough since mid-2019.)

Greenbrook, which also operates under the name McNam Management, has refused to renew market-rate leases during the pandemic and gave residential tenants a 90-day window to vacate their homes — a tactic which, though legal, flies in the face of the recommended pandemic policy of at least one landlord advocacy group.

There are also allegations of illegal attempts to vacate the buildings. Tenants and Lander say Greenbrook has been sending notices refusing to renew leases to rent-stabilized tenants, and some tenants accuse the landlord of construction harassment and endangering their safety. The Department of Housing and Preservation Development has initiated two harassment cases against Greenbrook.

Some free-market tenants have also hired a lawyer to investigate whether their units are actually rent-stabilized, and at least one lawsuit alleging illegal deregulation has been filed against Greenbrook by five tenants at 70 Prospect Park West.

Since May, tenants and Lander’s office have described the situation in letters and emails to various board members, including Davis, and asked the Texas Permanent School Fund to divest from its partnership with NW1 and Greenbrook.

Though the campaign got board members’ attention and became a point of discussion in a June meeting, the fund’s board was told that its consultant StepStone Real Estate had investigated the tenants’ grievances and found no evidence of improper or illegal conduct.

“This strategy has been in effect in the NYC market for many decades,” StepStone partner Steve Novick told the board. “It’s not something new. It’s absolutely not a predatory strategy.”

But board members continued to express concern and asked about withdrawing the fund’s investment.

“You may not call it predatory but it certainly is not typical of the investments that I saw when I looked over the materials,” said board member Rebecca Bell-Metereau. “Why do we have to hold on to this investment?”

John Grubenman, the Permanent School Fund’s director of private markets, later told the five board members who sit on its finance committee that the fund had also done its own due diligence and would continue to monitor the situation.

“As long as I don’t end up in court,” said Pat Hardy, another board member, during the meeting.

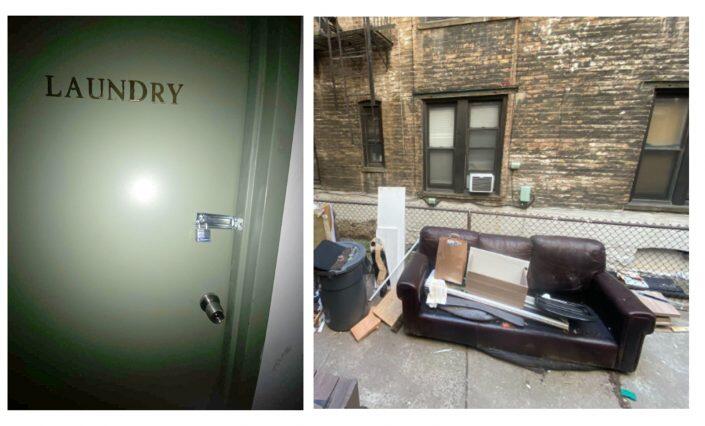

In response, a group of tenants wrote another letter to board members. This time, they included

Photos from a letter to Greenbrook’s board members

of a collapsed ceiling, a rat-infested couch and a padlocked laundry room. Davis said the dissonance between the tenants’ account and the fund’s description prompted her roadtrip.

“I really wanted to be able to see it for myself. And I’m glad I did because it wasn’t anything like what we were briefed on,” said Davis.

She had been expecting to find dilapidated buildings where a total makeover was warranted. Instead, she saw buildings in which tenants described having few issues until Greenbrook became their landlord. Tenants spoke of extensive dust, falling debris and sudden infestations of bed bugs, cockroaches and rats as Greenbrook began its renovations, prompting many former neighbors to pack up and leave. A few spoke about how they were fighting and negotiating to stay put.

Photos from a letter to Greenbrook’s board members

Greenbrook declined to comment.

“This has just been overwhelming,” said Davis, as she walked away from the final building on South Prospect Park. “There’s plenty of ways to make investments. We don’t have to put people out of their homes to fund Texas public schools.”

She said she plans to work with lawmakers back in Texas to introduce laws that would not only force the Texas Permanent School Fund to divest, but prevent it from investing in similar real estate strategies elsewhere.

How she will do that is anything but clear, but Davis also brought Casey Thomas, a Dallas city council member and former teacher, to join her on the tour. He said state pols would likely have to lead the way on any investment policies.

Davis said the State Board of Education’s chairman, Keven Ellis, was aware of her trip and had told her he didn’t support it. But she said she felt she was doing her duty. Ellis did not respond to a request for comment.

“Since I’ve been on that board I’ve been shaking things up and thinking outside the box and talking up for people who are disenfranchised and don’t really get a voice, so if there’s a consequence to that, then it is what it is,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said the Texas Permanent School Fund’s endowment was $23 billion, it is in fact nearly $50 billion.