On their way out the door, City Council members forever changed the future of Soho, Noho, and parts of many other neighborhoods.

In what was for many their final session, the lawmakers signed off on new zoning for the two Manhattan enclaves and several other contentious land use proposals. Because of term limits, most Council members are in their final month.

Here is a rundown of the major land use measures passed Wednesday.

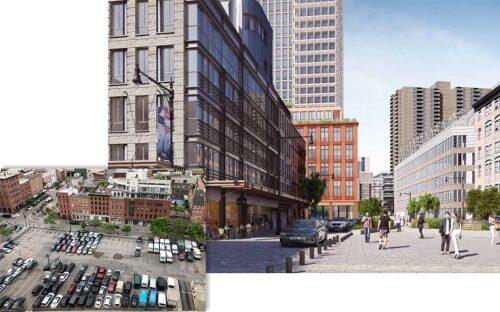

Soho and Noho rezoning

Mandatory Inclusionary Housing has long been criticized for exclusively targeting low-income neighborhoods. But when recounting Mayor Bill de Blasio’s affordable housing legacy, critics will likely point to the tail end of the administration as an exception.

The rezoning of Soho and Noho represents the second such initiative to focus on a predominantly white and affluent area, following the rezoning of Gowanus in Brooklyn. The change allows for residential and commercial uses in areas that had been zoned for manufacturing.

Despite its reputation as a retail hub, ground-floor retail was not permitted as-of-right in most of Soho. The zoning change lifts that restriction, but a special permit will still be needed for retail space larger than 10,000 square feet on narrow streets and 25,000 square feet on wide ones.

Opponents argued that the new zoning would endanger historic districts, displace rent-stabilized tenants and lead to outsized, mostly market-rate housing in the neighborhoods.

Last week the City Council reached a deal to reduce some of the commercial and residential density that had been proposed in some parts of the neighborhoods. It also eliminated “option 2” under the inclusionary program, in which 30 percent of apartments in new projects are set aside for residents making 80 percent or less than the area median income. The program’s other choices largely require deeper affordability.

Read more

Though there are no city-owned sites within the rezoning area, the mayor — whose final full day in office is Jan. 1 — did pledge to prioritize the construction of 100 affordable apartments on a city-owned parcel just outside the area, at 388 Hudson Street.

De Blasio also agreed to establish a SoHo/NoHo Arts Fund, which will be supported by payments made by owners who convert Joint Living Work Quarters for Artists into residential apartments. The City Council also passed a bill Wednesday that increases the fines for using such units for other purposes without formally converting them. The penalty for a first offense starts at $15,000 and is $25,000 for each subsequent one.

River Ring

(riverring.nyc)

Two Trees Development’s project flew through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure in just four months. The Jed Walentas–led firm began the process in August, and secured fast approvals from Community Board 1, Borough President Eric Adams and the City Planning Commission.

The pace of the review was a matter of survival for River Ring. Had it spilled into 2022, the developer would have had to deal with a new City Council member, Lincoln Restler, whose campaign platform implied he would have demanded even deeper affordability.

Instead, the project will include 1,050 apartments, of which 263 will be permanently affordable. Two Trees also agreed to pay for more than 150 new senior housing units within the community district and fund $1.7 million for neighborhood environmental improvements.

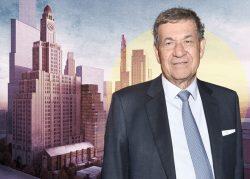

250 Water Street

(seaportvision.nyc)

After a long journey and a few haircuts, Howard Hughes’ project is moving forward. The apartment building, which will rise on a site that has been a parking lot for decades, will have 270 units, of which at least 70 will be affordable. The Texas-based developer has pledged to provide $40 million for 234,630 square feet of air rights from nearby Pier 17 and the Tin Building. The city will set aside that money and another $10 million of its own for the Seaport Museum.

Opponents have cited concerns over the prolonged construction and removal of mercury from the site, where a thermometer factory once stood.

FRESH expansion

In 2009, the city launched the Food Retail Expansion to Support Health Program, offering tax and zoning incentives to encourage developers to build supermarkets in so-called food deserts. The program has been underwhelming: Only 28 projects have been approved, and it is likely some would have happened even without the incentives.

The expansion will add 11 districts to the program’s current 19. The City Council also approved some limits on the residential increases permitted.

Hotel special permits

The City Council passed this text amendment at its Dec. 9 meeting, but the action was overshadowed by the Soho and Noho rezoning agreement.

New hotels, or expansions of existing ones by 20 percent or more, must first obtain a special permit. This policy has been rolled out in other areas of the city, including Midtown East, the Garment District and areas zoned for light manufacturing. In November 2020, City Hall abandoned its bid to apply a special permit requirement in Union Square, instead setting its sights on a citywide rule.

Critics of the plan, which included former and current City Planning officials, have argued that it unfairly targets one sector and lacks a land-use rationale. It also restricts new hotel development at a time when the hospitality industry is still reeling from the pandemic.

The administration has countered that the text amendment will support “more predictable development” and limit “the extent to which a hotel use may impair the future use or development of the surrounding area.”

Hotels that shelter homeless individuals, as well as those that were planned prior to the text amendment’s approval and are ready for occupancy within six years, are exempt from the permit mandate.

A lawsuit challenging the change calls the plan a giveaway to the Hotel Trades Council, saying it allowed the union to “exert political pressure to either block new limited-use hotels or require all new hotels to utilize a union workforce.” The measure was a high priority for the labor group.