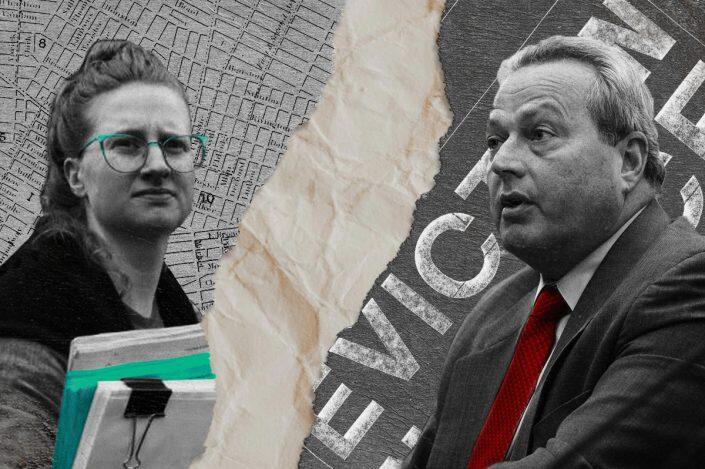

Housing Justice for All’s Cea Weaver and Rent Stabilization Association’s Joseph Strasburg (Illustration by Ilya Hourie for The Real Deal)

As the push for “good cause eviction” comes to a head in New York’s state legislature, the bill starts with one big advantage: a great name. Everyone agrees that people should not be evicted without good cause.

Try to define good cause, though, and things get a lot more complicated.

Like many laws, good cause would fix some problems and cause others. Will every politician carefully examine all of its ramifications before taking a position? It’s more likely that tenant activist Cea Weaver and landlord defender Joe Strasburg exchanged holiday gifts.

But, we’re here to help — examine the ramifications, that is, not get Weaver and Strasburg on the same page. That’s hopeless.

Let’s begin with a scenario:

An entrepreneur scrapes together money from relatives for a down payment on a run-down rental building in a struggling neighborhood. Putting his life’s savings and family’s future on the line, he gets a loan to buy and fix up the property. He lets tenants’ leases expire (evicting those who refuse to leave) and renovates the units with quartz countertops, stainless steel appliances and new flooring. He replaces the balky boiler and leaky roof, clears out the rats and roaches and adds some landscaping for curb appeal.

Would “good cause” allow this? No. The bill bans the evictions that would be necessary to transform the units.

What if the owner avoided evictions by temporarily relocating tenants to upgrade their apartments? First, he would have to get their consent. Then he would have to raise their rent enough to pay for the work. Those are huge obstacles; tenants don’t like to move, and good cause presumes that any increase of more than 3 percent or 1.5 times than the regional inflation rate, whichever is higher, is “unreasonable.”

The landlord would have to hire a lawyer and persuade a court that a greater increase is reasonable. The tenant, possibly with free legal services from the city or state, could argue that the upgrade was unreasonable because only modest repairs were needed to bring the unit up to code.

“I read the legislation as allowing landlords to increase rents for repairs and upgrades,” Weaver wrote in an email. “All the landlord needs to do is open their books to rebut the presumption if the tenant sought to challenge the increase.”

But a judge might rule upgrades unnecessary. Realistically, under good cause, no owner would pursue this approach. That is by design. In the real estate industry he is a “value-add investor,” but to good-cause backers, who have campaigned for the legislation as a way to eliminate this business model, he’s a “predatory landlord.”

Landlords might have an easier time persuading the court that a rent hike is needed to cover rising expenses such as heating, insurance and taxes. Still, that’s a hurdle. Owners whose annual costs rise 5 percent would probably cut back on maintenance rather than spend thousands of dollars on lawyers on a case that might not succeed.

That’s what happened during the pandemic when tenants became unevictable and some stopped paying rent.

Scant, contradictory data

The main benefit of good cause is that transience would decrease: People would stay in rentals longer and more would be spared the disruption and expense of moving, especially to shelters or dingy motels. Fewer at-risk kids would have to switch schools. Rent would be more predictable for tenants who remained in place.

Unfortunately, we don’t know how much the policy would reduce evictions. Few studies have been done, notes good cause backer Paul Willilams. He found one; it claimed that the eviction rates in four California cities through 2016 fell further (by 0.8 percentage points) after good cause was enacted than in similar cities without it.

The author of that study, Julietta Cuellar, calls the drop statistically significant, but does not give a clear context for it, and then contradicts her own claim:

“There is no significant drop in eviction rates … after the passage of the just cause eviction ordinance, except in the case of Glendale, nor do the trends among treatment and control cities change dramatically,” she writes.

Perhaps most surprising is that two of the four cities that passed good cause made less progress on evictions than similar cities that didn’t.

Specifically, her charts show that the eviction rate fell in East Palo Alto after good cause passed in 2010, but decreased further in similar cities that did not pass it. And in Glendale, the eviction rate actually went up after good cause passed in 2002, while it fell in similar cities without good cause. In Oakland and San Diego, the rate fell by more after good cause than in good-cause-lacking Long Beach and San Jose, respectively.

Read more

The upside of reducing evictions has been well documented, but good cause’s effects have not. Not only is data scarce and ambiguous, but New York’s bill differs from those passed elsewhere. Complicating matters, evictions across the U.S. are tracked only sporadically.

A probable downside is that fewer rental buildings would be built or improved and more would deteriorate. That means lower property values, less tax revenue and less work for plumbers, electricians, painters and other contractors. Again, we don’t know by how much, but it’s not nothing.

Paying attention, policymakers? Wait, there’s more.

The return of vacancy decontrol

Good cause is a form of rent control because it forces landlords to justify in court any substantial rent increase. Most landlords won’t risk paying legal fees for a case they might well lose. But it leaves a way for them to jack up rents without a judge’s approval: by getting tenants out without evicting them.

Good cause protects tenants, but unlike rent stabilization, it does not limit rents after they leave. When a unit becomes vacant, the owner can hike the asking rent by any amount.

Sound familiar? It does to New Yorkers. This policy, called vacancy decontrol, formerly applied to rent-stabilized housing.

Tenant activists hated it because it was an incentive for landlords to bully people out of their homes. It made rent-stabilized tenants enemies of landlords, rather than customers, and led to conflict and misery even as it funded property upgrades and empowered some tenants to negotiate five- and six-figure buyouts.

By publicizing the stories of construction harassment, ignored repairs and other abuses, groups including Weaver’s Housing Justice for All persuaded state legislators to kill vacancy decontrol for rent-stabilized units in June 2019. Ironically, these same advocates now want to impose it on all other rentals.

This has been overlooked, so it bears repeating: Good cause would bring vacancy decontrol to every rental unit in the state not covered by rent stabilization. It would give landlords an incentive to drive out tenants who don’t legally have to leave. That’s a recipe for strife.

Preventing abuses requires a level of enforcement that New York City failed for 25 years to achieve. There is no reason to believe it could be achieved across the entire state.

Weaver is not unaware of this, but offers a rationalization.

“While I am concerned about harassment and an incentive to displace, that exists already under the total lack of protections for unregulated apartments,” she said.

But landlords need not harass tenants to remove them from free-market units. They just let the lease expire.

In a free-market system, landlords want their rent-paying, law-abiding tenants to stay. New York’s version of good cause would reward owners who get them to leave. It would poison some relationships between landlords and tenants.

Good cause would also distort the rental market. Should a tenant leave, the landlord would raise the asking rent by more than 3 percent because it would be the only free chance to do so. Moreover, the policy would discourage the creation of rental housing, limiting its supply.

Those two factors would raise the price of available rentals. The higher cost would deter tenants from moving even when it is in their interest to do so, such as to escape a crime-ridden neighborhood, take a job in another city or enroll their kids in a better school. Housing stability is good, but policies to promote it can also trap people where they don’t want to be.

It is likely that if good cause became law, harassment of tenants would increase and Weaver’s army would pressure legislators to ban vacancy decontrol, as they did for rent stabilization. With rent hikes limited even for vacant units, upgrades of all rental housing would be stifled, as it has been for New York City’s more than 900,000 rent-stabilized apartments.

Let’s return to our hypothetical investor. Under good cause, he could still make money buying rentals. Restricting rent lowers a building’s value, which punishes the existing owner but makes it cheaper to purchase. A logical ownership strategy would be: do the bare minimum to keep the rentals habitable and incentivize tenants to leave.

New York lawmakers must weigh these outcomes against the potential benefits, and weigh the net result against the status quo. They must ask: Are lots of non-delinquent tenants really being evicted? And if so, would targeted programs such as one-shot deals and right to counsel be preferable to a sweeping one?

Longtime observers of state politics have no expectation that all 213 legislators will carefully consider these questions and not be influenced by rhetoric (such as comparisons to New Jersey’s good cause law, which forbids “unconscionable” rent hikes but lacks a numerical threshold) or political fallout (such as potentially being primaried by the Democratic Socialists of America).

But they did resist pleas to rush the bill through by Jan. 15, when the state’s eviction moratorium expired. Perhaps they balked at quickly enacting a permanent measure in response to a temporary situation — a predicted “eviction tsunami” that has yet to materialize in any state, and if it ever does, would largely affect non-paying tenants. Good cause doesn’t help them anyway.

The primary election and end of the legislative session are in late June. It’s going to be a fun five months.