Jersey City is poised to expand its inclusionary housing program, but its success hinges on developer buy-in.

Later this month the city’s Division of Planning is expected to present a plan that would create affordable housing overlays in areas of the city zoned for residential use.

Under the proposals, developers could build more units on their sites if they set aside at least 10 percent or 15 percent of the apartments as affordable.

Sites within low-, moderate- and middle-income Census tracts (where residents make less than 120 percent of the area median income) must have a 10 percent set aside, while those in upper-income Census tracts must have 15 percent.

Under the proposal, project scale could be based on “building envelope,” rather than a maximum-unit-per-acre standard, though height, floor area ratio, setback and other zoning rules would still apply.

In other words, the projects could be denser. Developers could also build multifamily in areas where it is not permitted as a “principal use.”

The proposal builds on an inclusionary housing ordinance that city officials approved in December. That measure employed the same affordable housing set-aside requirements, but applied to new residential projects that require a variance or rezoning (specifically those that needed additional approvals to have five or more residential units or 5,000 or more square feet of residential space).

Read more

The proposed changes would mean fewer regulatory hurdles for developers looking to bulk up their projects. In a statement, City Planning Director Tanya Marione noted that developers would simply need to seek approval from her agency rather than go to the City Council for a variance or rezoning.

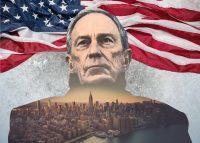

Jersey City’s inclusionary housing program hews more closely to the Bloomberg administration’s inclusionary housing program than to the system New York City adopted under Bill de Blasio.

The Jersey City and Bloomberg policies share a controversial quality: They are voluntary, offering density bonuses for affordable units.

The city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, on the other hand, requires a portion of apartments to be affordable if they benefit from a rezoning.

Critics have argued that the de Blasio-era policy largely targeted lower-income neighborhoods for rezonings and failed to provide enough deeply affordable housing. Previously, they complained that not enough developers were opting to include affordable units in their projects under the voluntary Bloomberg program.

Mandatory programs run a risk that the affordability requirements will undermine the economics of projects and prevent them from being built. Optional programs run a risk that projects will be built without affordable housing. Jersey City chose the latter, but set the affordability percentage at roughly half of New York City’s.