As ever, Joseph Hoffman’s mind was on the details. The Bushburg founder was driving through southwestern Brooklyn when he noticed a masonry supply showroom, a roadside discovery about as exciting to most as a gray Toyota Camry.

But Hoffman began puzzling over the possibilities — thousands upon thousands of possibilities lining the walls of that brick emporium, and whether any of them might be the missing piece of the puzzle at Empire State Dairy, his most ambitious and complicated development yet.

The 370,000-square-foot project, developed in partnership with Moinian Group, will bring a charter school, a grocery store and 320 apartments — mostly luxury — to East New York, one of Brooklyn’s poorest neighborhoods. It’s a project in a league of its own, but its centerpiece, a century-old former dairy factory, has proven a difficult anchor to build around.

Hoffman called John Woelfling, the Dattner Architects principal who is overseeing design on the project, which had already provided plenty of hurdles. The building is a city landmark, meaning inspectors hover over every structural alteration like moths to a lightbulb, and the project site straddles two different zoning districts, each with its own restrictions.

Woelfling has plenty of details to sweat, but on that day, Hoffman had a simple request: Come look at some bricks.

“Our approach for the new building was to be very cost-efficient,” Woelfling said of his initial designs. “But Joseph was never quite satisfied with it.”

In addition to restoring the former dairy factory to house the project’s commercial space, Bushburg will construct a 14-story apartment building that needs to blend in with its surrounding historic structures. Like the factory — which is actually four buildings made of different types of masonry — the new structure will be made of brick. But which color, which cut, which manufacturer? Light mortar or dark?

“What you’d think is a very limited set of choices, you start to come up with a complexity and variety of options that can be overwhelming,” Woelfling said.

Dattner and Bushburg spent months searching for a way to make their five-building Frankenstein win a beauty pageant. Eventually, Hoffman found just the shade of lipstick to make it work: a hand-cut brick somewhere in between the varied colors of the existing buildings’ century-old masonry. Hoffman also suggested carrying the old buildings’ quirky ornamentations over to the new structure.

Brick by brick, Bushburg has built itself to a fork in the road. After two decades of developing luxury residential and commercial projects in Brooklyn’s gentrifying neighborhoods — the name Bushburg is a portmanteau of Bushwick and Williamsburg — it could easily keep doing more of the same. But Bushburg isn’t content to just keep building out Brooklyn.

At a time of uncertainty for New York’s multifamily developers, Bushburg is hitting the gas so hard it might push straight through the chassis. It’s planning projects in Jersey City, Florida and beyond that will more than triple the number of apartments in its current portfolio. All that ambition comes at a cost.

If Bushburg wants to finance such megaprojects as its four-tower, 3,000 unit development in Jersey City, its relatively low profile could impede its fundraising. Now it’s ready to stick its head out from behind the bricks.

The development factory

East New York is one of Brooklyn’s most likely targets of gentrification, according to the city’s displacement risk index, which takes into account a neighborhood’s racial demographics, affluence and housing conditions. But it doesn’t behave like a gentrifying market.

According to the same city dataset, local rents have risen at a rate roughly on par with the rest of the city, but there’s no relative influx of higher earners.

The Empire State Dairy construction site in May 2022

So what’s Bushburg doing putting up luxury apartments — 75 percent of the units will rent at market rates — in a neighborhood where less than a quarter of households earn six figures? It’s the type of gamble the company is used to taking.

Bushburg was born out of another off-the-beaten-path opportunity. In 2005, the firm acquired an old pillow factory for $5.7 million — in a part of Bushwick largely devoid of foot traffic — and converted it into Shops at the Loom, a handicraft-heavy mini-mall that the press almost immediately counted out.

In a 2009 review that read more like a war dispatch than a look at an up-and-coming retail district, the New York Times reported “few signs of life” in the area, “except for the incessant rumble of heavy trucks and a muffled roar from inside a factory building.”

It seems that every time a new Bushburg project pops up, observers ask the same question: How will this development just beyond the hipster frontier work out?

“I respect the entrepreneurial spirit,” one local told the Times in a 2010 follow-up, “but I think it’s kind of insane.”

A founder, a Ranger and a showman

The C train was almost empty by the time it reached Van Siclen Avenue, where it deposited me a 10-minute walk from the Empire State Dairy site on Atlantic Avenue. Two- and three-story buildings lined the six-lane avenue in front of the former factory. The surrounding neighborhood seemed to be home to more mechanic’s garages and churches than shops and restaurants.

I met Jordan Franklin, Bushburg’s COO, near a parking lot. With his excellent posture, broad grin and Patagonia fleece, he looked as much like a tech founder as a real estate executive. The impression wasn’t wrong. Before joining Bushburg, Franklin co-founded Doorkee, a peer-to-peer rental platform that raised nearly $6 million in seed funding after the start of the pandemic. Bushburg was one of its investors.

In the past year and a half, as Bushburg has plotted its expansion, it’s hired executives from big competitors and the startup world to provide both hustle and institutional know-how. We were joined by Ford Sypher, Bushburg’s VP of leasing and operations, who came to the firm last year from Hudson Yards developer Related Companies.

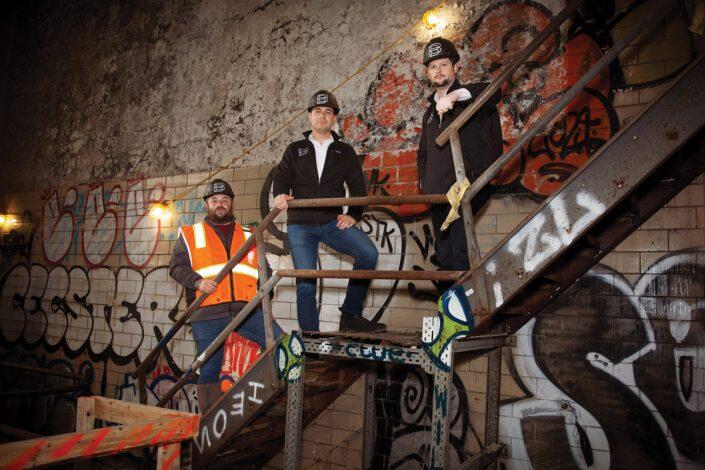

Sam Goldstein, who manages construction at the project, donned a tangerine safety vest and matte black hard hat with Bushburg’s new logo, a pair of thin, interlocking Bs. Sypher stood off to the side, quietly attentive; Goldstein, gregarious and broad-shouldered, led the way to the construction site.

We walked past an excavator toward the former factory, easily the largest building in the surrounding area. As we trudged through the soft dirt, it gave way around our feet like quicksand — terrible for my white sneakers but terrific for drilling foundations. All around us, metal shafts cut deep into the earth, making way for columns.

“It’s a beautiful soil,” Goldstein said. “We don’t hit rock, we don’t hit water.”

“It saves a lot of time,” Franklin added. “And expense.”

The old factory buildings, due to their landmark status, will save neither time nor expense. The facade will be entirely preserved, Goldstein explained, and it will be buttressed with a gigantic steel cage on all sides. But according to Franklin, the landmark also gives the project an edge in branding.

“We’re bringing a new asset class to East New York,” Franklin said. “It’s easy to look at a market where other people are building. If you look at Bushburg’s historic success, they are the first to plant a flag.”

Bushburg’s Sam Goldstein, Jordan Franklin and Ford Sypher

Goldstein was evidently obsessed with construction — his eyes lit up talking about silt quality and site safety routines. Franklin was similarly focused on efficiency and logistics. But after about half an hour, I still struggled to get a read on Sypher.

An Army Ranger who served three tours in Iraq and two in Afghanistan, Sypher came back to the States and worked for Team Rubicon, an NGO that sends veterans to help in disaster zones. What could someone who the Daily Beast once called a “danger junkie” possibly find exciting about leasing and operations?

“Operations is everything that happens or fails to happen,” Sypher said. “You can consider us the glue. You can consider us the people you call before you call 911. We’re here to ensure that when you turn that key and enter your apartment, you feel like you’re at home.”

I told him that was quite a poetic way to describe building operations.

Sypher considered for a second. “Well, it’s a lot more than clogged toilets.”

“Give ‘em a clock!”

In New York, large-scale luxury development requires as much finesse in the political arena as it does with a shovel. In the past, builders appeased hostile neighbors with such perks as public spaces or job creation. Lately, the name of the game is community appropriateness.

For evidence of that shift, one need only look at the demise of One45, a 51 percent income-restricted development in Harlem that local Council member Kristin Richardson Jordan rejected as insufficiently affordable for her community.

Bushburg has mastered the art of building those types of bridges. At PLG, a 26-story rental project in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Bushburg and its partner Moinian Group leased all 45,000 square feet of retail space to a charter school. What community would complain about getting a new elementary school?

When Bushburg purchased the Empire State Dairy property for $22 million in 2018, East New York was fresh off of a major rezoning. The change opened up roughly 190 blocks for higher-density development, with just one building selected for landmark designation: the factory. It was the type of expensive, timeline-stretching plot twist developers fear.

At the same time, there was a growing movement within East New York to preserve historic buildings. Zulmilena Then, a lifelong neighborhood resident and founder of Preserving East New York, began proposing landmarks at community meetings in 2015 to try to prevent the destruction of iconic buildings she had observed in other upzoned areas.

“These neighborhoods all have something in common: They have been forgotten by city planning initiatives for years,” she said.

Preservation groups honed in on the dairy factory’s camel-colored smokestack. Some were concerned that the project would obstruct views of it or cantilever too far over the historic buildings.

In a decision perhaps as pragmatic as it was altruistic, Bushburg decided to preserve the smokestack and extend the new building slightly over the factory roof. Then is still not pleased.

“East New York is family oriented,” she said. “When the project was proposed, they spoke about being a community-oriented project, but the number of units that they have available for studios and one-bedrooms is concerning. It’s just gonna be a transient development for the most part.”

Still, the project will preserve pieces of the historic structures, including the multicolored mosaics of cows and farmers adorning the Atlantic Avenue facade. The developer is even adding a new one: Early factory designs showed plans for a clock above the mosaics, but it was never built. As part of the negotiations, Bushburg decided to add it.

“Our instinct was, ‘No, we’re not going to provide a clock,’” Dattner’s Woelfling recalled. “But at one point, Joseph or Sholom [Laine, another Bushburg executive] said, ‘You know what, give ‘em a clock! We’ll get the approval and we’ll all be better off for it.”

Jersey boys

As it caps off Empire State Dairy, Bushburg is preparing to break out of Brooklyn. After two decades of building just past the crest of luxury development, that wave is pushing outside of the city itself. And as Bushburg’s reach grows, so does its ambition.

The most striking project in the firm’s pipeline is its Jersey City megadevelopment, dubbed Westview. If it’s approved, what’s now nine acres of “very well-located dirt,” as Franklin puts it, would host roughly 3,000 luxury apartments across four towers.

The size of the project bears repeating. Currently, across its entire portfolio, Bushburg controls about 1,500 apartments. Westview alone will double that.

The project would rise on the far west side of Jersey City, an area not known for its easy commute to Manhattan. But the city plans to extend its light rail system west of Route 440, cutting straight through the middle of Bushburg’s land.

“This is the next area to be built in Jersey City,” said Michael Campbell, CEO of the Carlton Group, which plans two multifamily developments of its own in the area. With a more favorable political environment for builders, Jersey City will soon boast additional transit options into Manhattan that rival those of the outer boroughs.

The race for community engagement has already begun. While the project isn’t expected to break ground until early next year, Franklin says he’s spoken with elected officials, New Jersey City University and a local nonprofit looking for internship opportunities.

“I take every single call, because that’s what it takes to be successful, but we also believe it’s the right thing to do,” Franklin said.