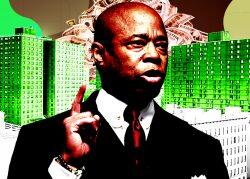

Current state of 201-207 7th Avenue and rendering of new property (Nisha

Shetty for The Real Deal, Amie Gross Architects, Getty)

A co-op in Chelsea for $2,500 seems like a castle in the air, especially when you compare the architect’s dreamy watercolor illustration of 201-207 7th Avenue to what’s there now.

But in 2024, life will imitate art. The property in Chelsea, which has been neglected for over four decades, was unveiled last week as the site for a most unusual affordable homeownership project.

The four distressed buildings along Seventh Avenue, which include 14 rental apartments, are to be razed and replaced by one nine-story building — designed by Amie Gross Architects — with 26 co-op apartments and ground floor retail.

Five tenants have been temporarily relocated and are attending co-op homeownership training. After the project is completed, they will purchase their new units for $2,500 (or $250 if their income is low) — an incredible bargain in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the city. The remaining 21 co-op units will be made available through the housing lottery to households earning 130 percent of the area median income.

“Our family is excited to come home as homeowners in our own community,” Keyla Espinal, one of the five original tenants of the Chelsea buildings, said in an Adams administration press release. “It’s a victory not only for the residents of the buildings, but also the whole neighborhood, which will see this corner of Chelsea transformed into something we can all take pride in for many years to come.”

Pamela Wolff, a preservationist, was also grateful, although she was one of first residents of the neighborhood to advocate for the renovation of the four buildings. “I’m praying for success for everybody involved,” she said at the groundbreaking.

The emotions were understandably high: The effort dates back 44 years. The previous landlord stopped paying property taxes — a common decision in the 1970s and 1980s when many buildings generated less revenue than they cost to run — and the city seized them.

Wolff blamed the long struggle largely on “inertia and bureaucracy.”

“The tenants couldn’t keep the deal going,” she told The Real Deal. “No one was willing to take charge of the situation.”

The solution was a co-op conversion, but it required a great deal of serendipity and many elements to come together.

The project is financed through a program of the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The Affordable Neighborhood Cooperative Program picks developers to renovate deteriorating, city-owned multifamily buildings to create affordable co-ops for low and moderate-income households.

The majority of current tenants need to support the conversion, have a financially viable plan, be willing to take on ownership and participate in the training.

Significant investment in financial and human capital is required over a number of years from various parties, which is a time-consuming process.

Banks need to be willing to make loans — with regulatory agreements and deed restrictions in place — and lenders have to be comfortable with the program model. Complicating matters is the banking and lending landscape has worsened since the pandemic. Recent changes to rent laws have also resulted in a harsher borrowing climate, along with worries about the inherited debt tied to any required renovations.

Getting financial partners on board also takes time and finesse. They need to be assured that their investment doesn’t come with major risks. They also need to be confident that tenants can manage the building over the long term.

And crucially, landlords need to be willing to sell the property at an affordable price. In this case, that was possible because the city owned the building — a rarity since the days decades ago when owners commonly abandoned their decrepit buildings rather than pay the back taxes.

“Successfully converting apartments into homeowner co-ops requires an enormous investment and years of dedication from the residents, the city, and partners,” a spokesperson for HPD said.

Neighborhood Restore is one such partner. It works with the agency by facilitating the transition of properties in physical and financial distress to qualified new ownership for stabilization.

Read more

Another is Asian Americans for Equality, the developer of the project. It has built or preserved over 1,200 units across the city. AAFE completed its first Affordable Neighborhood Cooperative Program project, at 244 Elizabeth Street in Manhattan, in 2017, creating 19 affordable co-op apartments. In addition to the Chelsea project, the organization is transforming three buildings in the East Village, creating 44 homeownership opportunities.

But what made this project especially complex was that it required demolition and ground-up construction, which entails a significant financial and staffing commitment over several years.

Thomas Yu, the executive director of the organization, said it involved “often acting as social workers” to communicate with and temporarily relocate tenants, paying architects and engineers, and serving as the financial guarantor for the project — “a big burden for any nonprofit.”

Financing the Chelsea project also required hefty subsidies. The development cost of $25.7 million includes HPD subsidies in excess of $16 million; a construction loan from a charity, Enterprise Community Partners, in collaboration with another mission-driven nonprofit, the Low Income Investment Fund, of about $8.2 million; a deferred developer fee of $1 million and a developer equity and reserves of about $414,000. Further funding will come from sales proceeds of the 21 vacant co-ops (but not much, given the low prices). The Manhattan borough president kicked in money, too.

The city provided the property for free. “It would not be feasible to create an affordable homeownership project, especially in neighborhoods like Chelsea where housing costs are especially high, if land acquisition were required,” Yu said.

Enterprise’s construction loan was fixed at a below-market 5.5 percent, and it has a 30-month term to coincide with the construction, according to Theresa Cassano, the senior loan officer at the organization.

Enterprise, a community development financial institution and a longtime partner of Asian Americans for Equality, has a lending volume of about $50 million annually in the city — which is not limited to affordable housing. That doesn’t go very far in New York City development, so it has to be selective in choosing projects and often to piece together its own resources with public and private sources. Enterprise is rarely the sole lender on a development.

“There’s a really limited pool of lenders for these types of deals,” Cassano told TRD. “They tend to have higher perceived risks, and they’re very complicated transactions. What got us comfortable here was having a really trusted community partner, and a lot of subsidy support for the project.”

At the closing of the construction loan last month, 201-207 7th Avenue was transferred to Restoring Communities HDFC construction. The final product will be owned and managed by the residents.

Demolition is set to begin this month. Construction is expected to start early next year and take two years.