If you want to get in touch with DBOX, don’t reach out on LinkedIn.

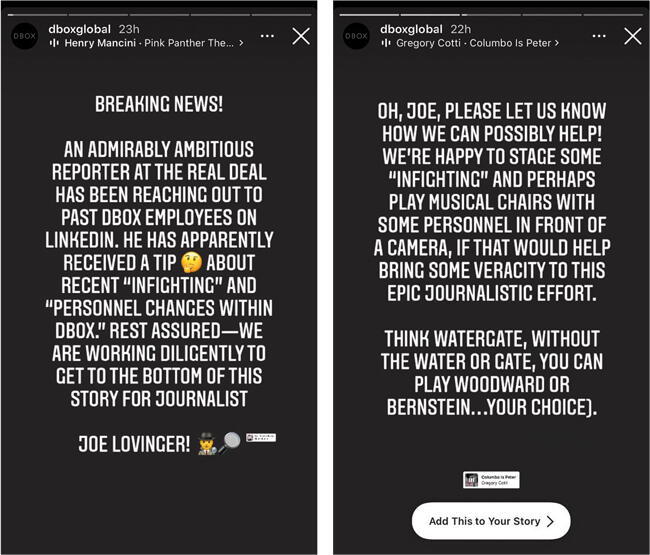

In July, The Real Deal messaged former employees of the real estate marketing company to discuss a tip about infighting at the firm — a tip that the reporting did not bear out. The following morning, DBOX co-founder Matthew Bannister wrote and tagged the reporter in a series of posts on the company’s Instagram account.

“Breaking news! An admirably ambitious reporter at TRD has been reaching out to past DBOX employees on LinkedIn,” one post read. “Oh, Joe, please let us know how we can possibly help? We’re happy to stage some ‘infighting’ and perhaps play musical chairs with some personnel in front of a camera, if that would help bring some veracity to this epic journalistic effort.”

“Think Watergate, without the water or the gate, you can play Woodward or Bernstein…your choice.”

The posts, set to music from “The Pink Panther” and “Columbo,” featured prominently on DBOX’s Instagram profile for weeks, just above a grid of images showcasing the company’s marketing work for 432 Park Avenue, Macklowe Properties’ Billionaires’ Row skyscraper.

“That was a way to get you to come and talk to me,” Bannister said in an interview. “You got your 15 minutes of fame.”

The response came as no surprise to several former DBOX staffers.

“It’s almost cultish how loyal they are to the brand,” said one. “They don’t question, they just accept.”

For a quarter century, DBOX has translated cocktail napkin sketches of luxury real estate developments into renderings, videos, brochures, sales galleries, books and websites. Its clients include Steve Ross, Larry Silverstein, Harry Macklowe and Steve Roth — developers who count their dollars and square feet by the millions — and its specialty is the details that turn browsers into buyers. It won an Emmy in 2012 for a documentary series, produced by Steven Spielberg, about rebuilding the World Trade Center.

Former employees describe Bannister as a talented artist with befuddling business instincts.

Bannister recently moved to Seattle, where DBOX doesn’t have an office. Other employees work from studios in New York, Miami, London, Budapest and Lviv in western Ukraine. As the company has spread out after the pandemic, Bannister says, he has delegated more control to those executives, choosing to focus on one or two projects at a time. In an interview, Bannister said he didn’t know how many employees DBOX has (73). Same for its estimated market share.

“I’ve got no idea, and it’s not something that would ever concern me,” he said, reiterating in a follow-up response that “‘market share’ can go jump in a lake.”

Asked about DBOX’s annual revenue, Bannister responded, “What’s your salary/income Keith and Joe…also how much do your partners make?”

Why should anyone care about DBOX? Well, how do you distinguish one glass pencil from another? A Robert A.M. Stern-designed mausoleum on 84th from one on 68th?

You tell the best story.

That’s why Harry Macklowe gave DBOX $1 million to shoot a four-minute promotional film for 432 Park Avenue. That’s why DBOX structured the website for Naftali Group’s 200 East 83rd in five “chapters” like an epic book rather than a sales tool. New York has no shortage of ultra-luxury condos, and developers turn to DBOX to sell their supremacy amid increasingly homogeneous products.

DBOX uses its renderings to lure clients into buying its full marketing suite, including video and web design. No picking and choosing allowed: The firm only works with those who buy the whole cow.

The technology used to create these mockups has grown more powerful, but also more accessible. Low-cost competitors in Europe and India produce renderings for a fraction of what DBOX charges.

Bannister isn’t concerned. Plenty of developers are still willing to pony up for primo marketing.

“DBOX is the most expensive by far, but they have a brand — they set the bar many, many years ago, and we were all followers,” said Gonzalo Navarro, founder of Miami-based creative agency ArX Solutions.

Instagram screenshots of posts by @dboxglobal after TRD contacted its ex-employees

Still, with some marketing budgets shrinking and a possible recession looming, DBOX’s hefty price tag is becoming harder to ignore. And as competition mounts, some former employees say DBOX underpays what its competitors offer for similar work.

“Just before the performance review, they’d be the first to say that there is no budget for salary raise,” one ex-designer recalled.

In an email, Bannister called the claims that his firm underpays employees “absolute twaddle,” reiterating that money has never been DBOX’s guiding light and copying a pair of finance and management employees on the email thread.

“Alex and Jon (who do our business management and finances) could shed some light into how I as a founder and CEO am considerably underpaid to ensure that all staff are paid as much as the company can afford,” Bannister wrote.

Alex Carter, a business and finance associate at DBOX, added that he has seen senior employees make sacrifices to increase compensation for junior ones. “That starts with Matthew and is true across senior management,” Carter said.

“We pay our staff as much as we possibly can without going into the red,” Bannister wrote. “End of story.”

“There was no business plan”

DBOX has always been a business in a very loose sense of the word. Bannister and his two co-founders, Charles d’Autremont and James Gibbs, started the firm in the mid-’90s while playing in a band called Release. They used the proceeds to buy bigger amps and better guitars.

“There was no business plan. We’ve never been that way. We just did what we did, and we’ve ended up where we’ve ended up,” Bannister said.

They started DBOX at a time of upheaval in real estate marketing. Computers were overtaking slide rules — the company name comes from “Dialog Box,” the title of a course the founders taught at Cornell about the then-revolutionary idea of using computers as interactive design tools. DBOX’s niche was the kind of high-tech visual work that was shifting from a novelty to a nonnegotiable.

Then came the condo boom of the 2010s. As Billionaires’ Row was rising, DBOX scored the marketing contract for 432 Park Avenue, the matchbox-like supertall developed by Harry Macklowe and CIM Group.

While Macklowe and DBOX executives now talk about each other like family, their collaboration started with some discomfort. In the pitch meeting at the developer’s offices, Bannister spread samples of DBOX’s past work across a conference table, forming a mosaic of marketing books and brochures. Each text was carefully placed, with the best hardcover volumes near the head of the table, where Bannister assumed Macklowe would sit.

But Macklowe didn’t go to the head of the table. He made a beeline toward the center of the spread and snatched up a floppy booklet made for a Midtown rental building — Bannister’s least favorite of the bunch, which he had hoped would hide in plain sight.

Macklowe stared, first at the book, then at Bannister.

“Why do you think you can get this project?” the developer asked.

Any initial discord soon wore off, and DBOX won the account.

“You can’t just go to someone else because they’re less expensive,” said Macklowe marketing director Richard Dubrow. “A Silverstein, a Macklowe, a Vornado, they need that quality to realize their project.”

A DBOX rendering of a bathroom at 432 Park (Courtesy of DBox)

Throughout the meetings, Macklowe referenced artistic and cultural touchpoints he thought his wealthy clients would associate with quality. Bannister and DBOX senior partner Keith Bomely incorporated them into the building’s marketing campaign, and even inspired some high art of their own: Leidy Churchman’s “Tallest Residential Tower in the Western Hemisphere,” an oil painting held by the Whitney Museum, was based on DBOX’s rendering of a bathtub overlooking Manhattan from its vantage point near the top of the skyscraper.

“They bring some kind of intangible to it that’s not just the computer program,” said Dubrow.

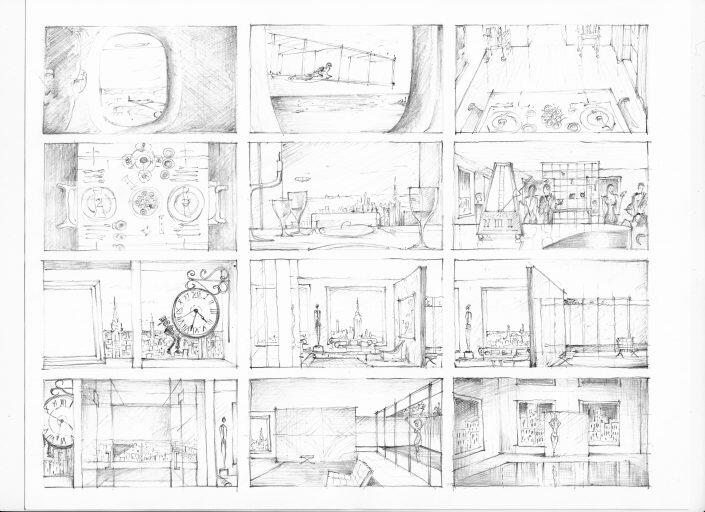

The campaign’s pièce de résistance — a $1 million film that runs just over four minutes — name-checks King Kong and Charlie Chaplin. French tightrope walker Philippe Petit, who famously traversed a wire between the World Trade Center’s Twin towers in the 1970s, tiptoes across the skyline to a party at 432 Park.

The film ends with a classic DBOX rendering: As cars bottleneck on the streets in a thicket of noise, the skyscraper stands serenely among the clouds.

While DBOX largely caters to skyline shapers, it branches out now and then. Bannister worked on a branding initiative for luxury residential brokers Oren and Tal Alexander. The work includes a black-and-white advertisement showing the brothers in tuxedos, like a pair of James Bonds hoping to sell you a $30 million mansion.

“He is probably one of the best architects I know that is not an actual architect,” Oren Alexander said of Bannister.

Bannister isn’t always the easiest to work with, a perception he doesn’t dispute.

“Is it my job to be easy to work with, or is it to produce great work that actually does what the client needs to sell?”

Digital debacle

Issues regarding personnel and business management boiled over in a dispute with a former contractor, Grant Powell.

In 2015, DBOX planned to spin off its digital and social media work as a separate company, DBOX Digital. DBOX’s principals hired Powell to lead the expansion and promised him a 44 percent stake in the new company.

Just two years later, DBOX was locked in a lawsuit against Powell. In Bannister’s account, Powell was “plainly lacking in relevant experience,” and clients were venting their frustrations weekly.

Powell promised to pull a marketing bigwig from Google to DBOX Digital, Bannister claimed, but refused to name him. A planned lunch fell through, and the Google guru never materialized.

“That was the first red flag,” Bannister told the court.

By the end of 2017, the DBOX Digital’s board decided to fire Powell, claiming it had that ability because there was no signed operating agreement. Bannister alleged that Powell drained the spinoff business’ bank account, pulled $135,000 into a separate account with just $8,000 left behind and locked employees out of their work emails.

Sketches by Matthew Bannister for 432 Park Avenue’s promotional film (Courtesy of DBOX) Click to enlarge

Powell had a very different recollection. After he arrived at DBOX Digital, he realized profits were not appearing on its books. The reason: No one had been invoicing clients, according to his affidavit.

DBOX Digital’s finances were in such bad shape that Powell said he had to loan the company about $50,000 from his personal savings so it could make payroll. But after establishing an invoicing system and bringing in new clients, DBOX Digital was turning a profit. By December 2017, it held cash and accounts receivable over $1.3 million, according to Powell’s affidavit.

“Bannister realized he had negotiated away a significant minority share of what now was a money-making operation, and wanted his piece of the DBXD pie,” Powell said in his affidavit.

Powell said he never took DBOX Digital’s funds or locked employees out of their accounts and that Bannister had agreed to an operating agreement, despite his claims to the contrary.

In 2018, the two sides settled and the suit was discontinued.

“Matthew Bannister has a certain way of doing business, which is a different way than the way I do business,” Powell told TRD. “This led to a disagreement which we settled and parted ways.”

Architectural visualization is a niche field, and DBOX focuses exclusively on the high end of that niche. But it still faces competition from firms like Hayes Davidson, which handled visualizations for JDS Development’s 111 West 57th Street, and Binyan, the Australian shop that worked on Related Companies’ 15 Hudson Yards and Lightstone Group’s 130 William Street.

Some developers outsource to low-cost international competitors, but “some months later they come back to you,” ArX’s Navarro said.

“If everything was price, they’d be out of the market tomorrow. But the service,” Navarro added, “they just give something else that nobody can give you.”

Still, some smaller, newer architectural visualizers have managed to score high-profile contracts. For its $2 billion Innovation QNS development, Silverstein and ODA Architecture tapped Netherlands-based VERO Digital for visualizations. Founded in 2016, VERO has also scored jobs from Zaha Hadid, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Kohn Pedersen Fox.

As smaller firms improve their capabilities, marketing budgets are getting tighter, even on the most luxurious projects. Part of that decline is because of the shift to digital offerings, which cost less than brochures and books. Particularly well-heeled marketing chiefs may get up to 3 percent of a building’s budget, but industry sources say it often falls closer to 1 percent, and has to cover everything from sales galleries to promotional films to parties for brokers.

Few doubt that DBOX does great work. Their books look like bestsellers. Their sales galleries emanate luxury. But the question is whether that work justifies the cost.

“Certain clients know exactly what my value is,” Bannister said. “Some of them treasure that, and some of them waste that. They waste my ability.”