Sterling Bay executives presented their updated pitch Thursday night for the 53-acre Lincoln Yards super-development, previewing a pair of office buildings and a network of green spaces designed to win over neighbors pushing for more parkland.

The developer stuck with the same infrastructure guidelines it presented the last time it went public in July, proposing to extend Dominick Avenue as the area’s main thoroughfare and build three new bridges across the North Branch of the Chicago River.

An overlay diagram of the latest proposal for Lincoln Yards

But the company revealed Thursday it would kick off the $5 billion project at the far northern edge of the site with a cluster of streetscape makeovers and mid-rise buildings that would trace the river between Webster Avenue and Cortland Street.

The existing CH Robinson headquarters at 1515 West Webster Avenue would step up to two new modernist office buildings the developer is calling “21st Century Lofts,” which would include inset terraces and respectively measure 220 and 250 feet tall. An above-ground parking garage would be built immediately to the east to service the entire development.

The first phase would also create a tree-lined pedestrian “slipway” leading into the site from Southport Avenue and a partial extension of Kingsbury Street. Scott Duncan, a partner at lead architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, said Kingsbury would be a “shared street” like Argyle Street in Uptown, but a diagram of the road showed distinct sidewalks and unprotected bike lanes.

“It’s important to be able to create a destination on day one, and create a sense of neighborhood immediately by defining the streetscape,” Duncan said. “At this point, the site is so empty that putting a single building there wouldn’t really achieve that.”

Planners also shaved a combined 100 stories off the heights of buildings across the development since the previous version of the proposal, including lowering its tallest building from 800 feet to 650 feet. But principal Keating Crown said Thursday the site still would be built to accommodate up to 5,000 residents and 23,000 permanent jobs, the same benchmarks the company set in July.

Sarah Astheimer, a principal of the landscape architecture firm James Corner Field Operations, showed lush renderings of the seven publicly-accessible parks and plazas being proposed under the expanded 21-acre collection of open spaces.

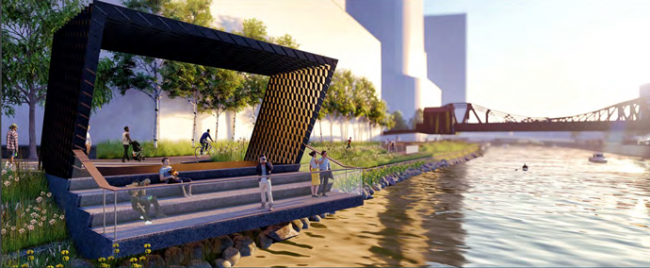

The north section of Lincoln Yards would include a “foundry playground” with tube slides that mimic the Finkl Steel foundry, a “furnace garden” with open firepits, a “great lawn” facing the river and three overlook decks allowing people to step down to the water.

Plans for the south section of the site include two soccer fields and a baseball field just north of the 20,000-seat stadium where a United Soccer League expansion team would play.

Sterling Bay and city officials have both pointed to a proposed “transitway” between Downtown and Lincoln Yards as a key to managing the heavy traffic that would accompany a professional sports venue. But few details have been released on the proposed route, including which agency would operate it.

“Overlook decks” over the North Branch of the Chicago River

Alderman Brian Hopkins (2nd), who earlier this year moved to block City Council discussion of the proposal until it earned his approval, said he was noncommittal on the newest version of Sterling Bay’s plan but said that “there seems to be something close to consensus for something like” it.

The alderman also rebuffed a resident’s request to hold his decision until next year’s mayoral election, saying he would not “intentionally slow it down for no good reason.”

Earlier this month, city planners proposed creating a new tax increment financing district they said could raise up to $800 million to help fund public infrastructure improvements around Lincoln Yards.

Erin Lavin Cabonargi, Sterling Bay’s former director of development who presented Sterling Bay’s plan during the July meeting, has since left the company to run her own development and consulting firms.