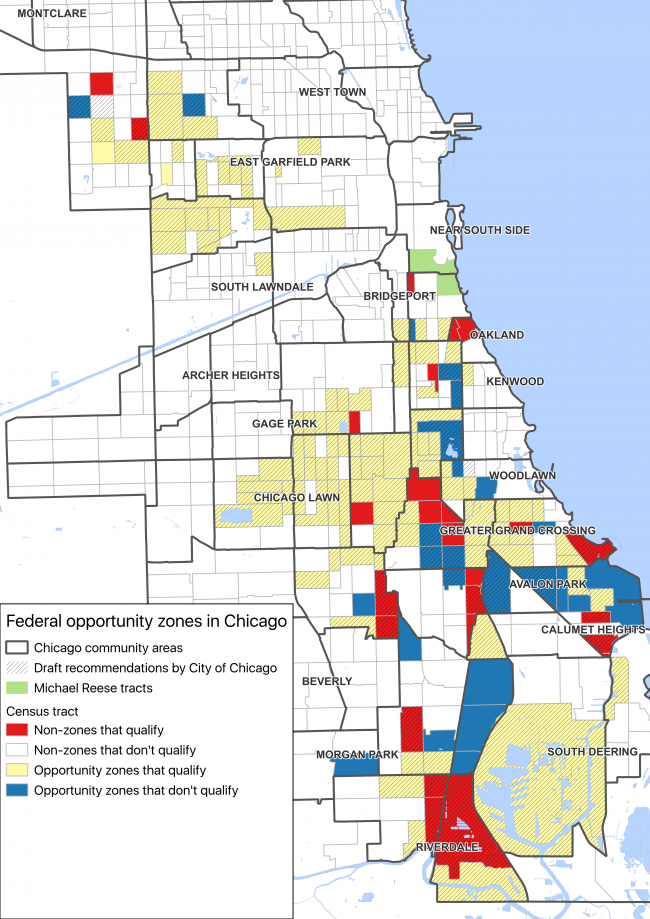

Updated May 1, 4:56 p.m.: Most of the 135 Opportunity Zone Census tracts in Chicago trace a familiar path through the city’s most economically distressed neighborhoods, highlighting sections of the South and West sides with dwindling populations and scant new construction on the horizon.

(Map by Haru Coryne)

But two of the zones, which wind along a more developed section of lakefront two miles from Downtown, don’t resemble the others. Crossing into both is the former Michael Reese Hospital complex the city bought 11 years ago. The 49-acre site would have been the Olympic Village in Chicago’s failed bid for the 2016 Summer Games, and more recently, Amazon’s second headquarters in that unsuccessful offering.

Just before the Opportunity Zones selection process got underway last year, Chicago officials chose a team of private developers to embark on a $2 billion megaproject on the Michael Reese site. The pending project was already in line to collect city funds for the construction of a new technology campus, but would now stand to gain significant federal tax incentives with the Opportunity Zone designation.

But when city officials drew up an initial list of proposed Opportunity Zones, it did not include the Reese site. The sprawling property did not meet the city’s original guidelines for neighborhoods in need of more investment. Despite that, state officials intervened in spring 2018 to personally add those two tracts, according to interviews with those involved and emails obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests.

That action highlights a nagging criticism leveled against the Opportunity Zones program. Skeptics contend the initiative, meant to lift up distressed neighborhoods, may instead serve to enhance gains on projects that developers already intended to build.

The 100-acre assemblage of public land that includes the Reese site is now split between two designated Opportunity Zones. That will likely help developers raise the $735 million in equity investments they outlined two years ago as part of their plan for the site, to be renamed the “Burnham Lakefront.” The potential is so great that the Reese site tracts could become the most lucrative of all the Opportunity Zones in the state.

The city’s chosen developers for the project include Farpoint Development. Led by Scott Goodman, Farpoint has teamed up with Clayco on the newly-formed Decennial Group Opportunity Fund — unveiled in early April — making the Reese site its centerpiece.

Goodman “did not have any conversations with any state or city officials concerning [Opportunity Zone] tract designation until well after the zones were designated,” he wrote in an email.

Criteria for selection

Most of Chicago’s Opportunity Zone tracts were chosen because they fall under a set of criteria used by the city as a benchmark for struggling neighborhoods: a combination of at least 20 percent unemployment, a 30 percent-plus poverty rate and median family incomes below $38,000.

Of the 135 tracts chosen in Chicago, 27 fail to meet at least one of these standards. Eight zones, including the northern Michael Reese tract, meet none of them. That tract’s median income is more than $83,000, Census data shows.

The inclusion of the Reese site stood out in part because of how closely city and state officials had otherwise stuck to the Opportunity Zone’s original mission of lifting up high-poverty neighborhoods, said Geoff Smith, director of the DePaul University Institute for Housing Studies.

In a report published earlier this year, the institute called attention to three of the 135 zones where property values had already been relatively high and rising rapidly before they were selected as Opportunity Zones. The northern Michael Reese census tract was one of them. The other two were on the Near West Side and in the Illinois Medical District.

“From what we found, the city basically did a good job of identifying tracts that were under-invested,” Smith said. “But there were a few exceptions that we flagged with rising prices and growing demand for housing, that could be potentially vulnerable to displacement.”

Created as part of the 2017 federal tax overhaul, Opportunity Zones open a range of tax incentives for developers and investors who can substantially raise the value of land in certain distressed areas and hold on to the properties for 10 years. In spring 2018, state governors were allowed to nominate tracts.

In Illinois, it fell to then-Gov. Bruce Rauner to decide which of the state’s 1,305 eligible Census tracts to designate as Opportunity Zones. On April 20, 2018, he submitted 327 tracts to the U.S. Treasury Department, with 135 in Chicago — including the two Reese tracts.

Chicago’s choices, mostly on the city’s South and West Sides, had been drafted by a trio of top city officials including Aarti Kotak, Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s chief of staff for neighborhood economic development. In an interview, Kotak said she compiled the list alongside city planning department Commissioner David Reifman and then-Deputy Mayor Robert Rivkin.

Email sent, change made

Kotak, Reifman and Rivkin acted on guidance from Emanuel to “make sure those communities most in need got the most benefit,” Kotak said.

She added that Chicago leaders sought to avoid the maps drawn for cities like San Francisco and New York, where part of Amazon’s now-abandoned Queens campus plan had been designated an Opportunity Zone.

The three officials drew their map based on the benchmark criteria for poverty, unemployment and average income. They then discarded 15 proposed zones after consulting with various aldermen who suggested other tracts where “we know there is momentum for development,” Kotak said.

On March 9, 2018, Kotak sent an email to senior Rauner administration officials Sean McCarthy and Lanae Clarke, with an attached list of 133 tracts. They did not include the two tracts comprising the Michael Reese site.

About 40 minutes later, records show, Kotak sent another email to McCarthy and Clarke — CC’ing Rivkin and Reifman — saying she had added the two Michael Reese tracts to the list “per my conversation with Sean.”

After state officials switched out about a dozen more tracts, the Reese tracts and 133 others were ultimately certified as Opportunity Zones.

Kotak denied any undue influence was exerted on the selection process. The two Reese zones were chosen because they are “challenged tracts,” she said, that city and state leaders all understood would be added to the Opportunity Zone site list. Though relatively wealthy and close to Downtown, the east edge of the tracts is “isolated” and bisected by Metra rail tacks, making them especially hard to build around, she said.

“The Michael Reese tracts are a priority for the city and the state,” Kotak added. She cited their proximity to McCormick Place and the “need to better compete for convention business, given the gateway it provides to the broader South Side, and the need to pull up that part of the city.”

The Reese site was among several tracts where the city appeared to prioritize accelerating existing proposals over jump-starting new ones.

“The city was trying to be strategic in attracting investment” in the Reese site and other high-value parts of the city, Smith said. The combination of Opportunity Zones and current market forces could “drive up values of areas where investments are already happening.”

Alderman Sophia King

City officials never consulted Alderman Sophia King, whose 4th Ward includes the entire Michael Reese site, about the Opportunity Zone designation, according to King chief of staff Prentice Butler. But Kotak contends the mayor’s office met with the alderman about the zones.

Butler said the alderman still “wants to better understand what happened in terms of the selection process and the conversations that may or may not have happened to get there.”

Developers at the table

The city has owned the massive lakefront site containing the Reese campus since 2008, when it bought the land for $86 million. In 2016, the city’s planning department issued a request for proposals for a private entity to redevelop it.

Eight months later, officials chose a proposal for a “commercial research and innovation district” from a venture including Farpoint, McLaurin Development and Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives.

The group is still negotiating a sale agreement with city officials, but the application they submitted in early 2017 included a $144.5 million offer to buy the entire property in phases.

Kotak said she did not personally consult members of the development team during the Opportunity Zone tract selection process in early 2018. She also downplayed the likelihood of the “innovation district” proposal becoming reality, saying that the “selection of a team doesn’t mean anything as far as the development getting done.”

Even with the selection of a developer, she said, “that site is still going to require environmental and infrastructure work in the tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars. So if Opportunity Zones help accelerate investment in a site that’s been dead for a decade, we were happy to include that as a tool.”

Clarke and Reifman both declined to comment on the decision. McCarthy, now a regional executive with Comcast, did not respond to requests for comment.

“In the mix”

On March 12, 2018, three days after Kotak sent the city’s amended list of recommended Opportunity Zone sites, Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives president David Doig emailed McCarthy and Clarke. Provided was a list of six Census tracts he asked to be designated as Opportunity Zones, including three surrounding the Reese site.

“There was a very short timeline from when the legislation was approved to when the governor had to designate them, so we just wanted to make sure we were in the mix,” said Doig, who was superintendent of the Chicago Park District from 1999 to 2004. The Reese sites made sense as Opportunity Zones, he added, because they include vacant land the city has “wanted to see developed for a long time.”

In February 2017, when the Farpoint-led coalition submitted its proposal to redevelop the Michael Reese site, the Opportunity Zones program was not on its radar. But its application did outline a patchwork of tax credits and other public financing levers it would seek to help jump-start the proposal. Those included tax increment financing, environmental cleanup grants, New Market Tax Credits and city and state transportation grants.

When the Opportunity Zones program rolled out, things changed. Without the benefits investors can enjoy from Opportunity Zones, “a platform like Decennial Group wouldn’t exist,” the venture said this month when the Treasury Department released its latest regulations regarding the program. And it added, the venture “wouldn’t have a pipeline of deals under consideration throughout America’s Heartland.”

This story was updated to clarify the guidelines used by the city as a benchmark for selecting Opportunity Zones.