Call it commercial real estate’s Craigslist moment.

Downtown office sublease inventories across the country are chock full of once-desirable spaces that their current tenants no longer want, and brokers are shopping their leases in hopes of finding a taker on a secondhand deal.

Rather than handing space directly back to landlords when they scaled down their office use to go remote or hybrid during the pandemic — a move that usually comes with a hefty early exit fee — many tenants gave subleasing a try. The process typically involves backfilling excess with a sublease to another firm, called a subtenant, that comes in and usually pays cheaper rent to the contracting tenant, called the sublandlord.

The sublandlord typically offers the subtenant a more flexible leasing arrangement than in a standard deal. And it allows the sublandlord to reserve the option to move back into its space in the future and resume paying the full rent to the building owner itself.

Few markets, if any, have as much of this secondary space on the market as downtown Chicago, where tenants are looking to shed a collective 8 million square feet, a record high for the city.

There’s different levers to pull when negotiating a deal in the sublease market, and the brokers are performing a bit of role reversal. Since tenants drive the sublease market, it’s their brokers who are marketing spaces on behalf of the companies cutting back on offices. That means it’s the tenants reps who are seeking out other potential tenants while trying to refill the space — a job that brokers who represent landlords normally do in a tighter market.

Instead of haggling with brokers whose clients are landlords, these days getting a lease done might mean working with a fellow tenant rep who is normally a competitor.

“It’s a completely different game. You have to be buddies with the other tenant rep brokers,” said CBRE’s Bill Sheehy, who represents the tenant Evolent that’s marketing 122,000 square feet for sublease at 300 South Riverside Plaza in the West Loop. “Even though we compete, you never know when you’re going to run into someone you want to do a deal with.”

Recovery rental rates — the amount of rent paid by the subtenant compared to the full rent the original tenant pays the building owner — vary widely. A recovery between 30 to 50 percent of the original rent can be achieved at the lower and middle sections of the scale, Sheehy said.

In better times for office owners, tenants claw back more on their sublease offers. Recoveries run as high as 60 percent to 70 percent of the original rent when there’s less vacant office space than today’s record-high amount in downtown Chicago, said Savills’ Eric Feinberg. He’s marketing an approximately 40,000-square-foot space that the American Bar Association is subleasing at 321 North Clark Street.

“When we tell some tenants it’s a 50 percent recovery, they don’t want to hear that,” Feinberg said. “They want to market it at something higher. The demand is a little weaker right now, but for certain circumstances, buyers still exist.”

Brokers often remind tenants that the amount of time a space spends on the secondary market without being leased again costs money as their rent for the building owner comes due each month. That can help ease the pain of cutting rental rates on a sublease.

Some spaces in older Loop buildings are dipping below $20 per square foot in gross rental costs on subleases, less than half of what they might be rented for in a deal directly with a landlord. They’re finding out there’s not a lot of takers, even with the discount, said Allen Rogoway with Cresa, a brokerage that, like Savills, represents commercial tenants exclusively.

“Our world has changed in a way that we are constantly thinking about which tenants are repositioning to what size of space, and that game of Tetris of putting two parties together,” Rogoway said. “Whereas it was tenant-landlord action, now it’s a lot of sort of occupier-occupier. If you can find the two corporate entities that you know match up, that’s where you need to play ball.”

Even tenants of brand new skyscrapers and the trendy Old Post Office are backing away from their spaces, and asking their brokers to help reduce real estate costs through a sublease deal.

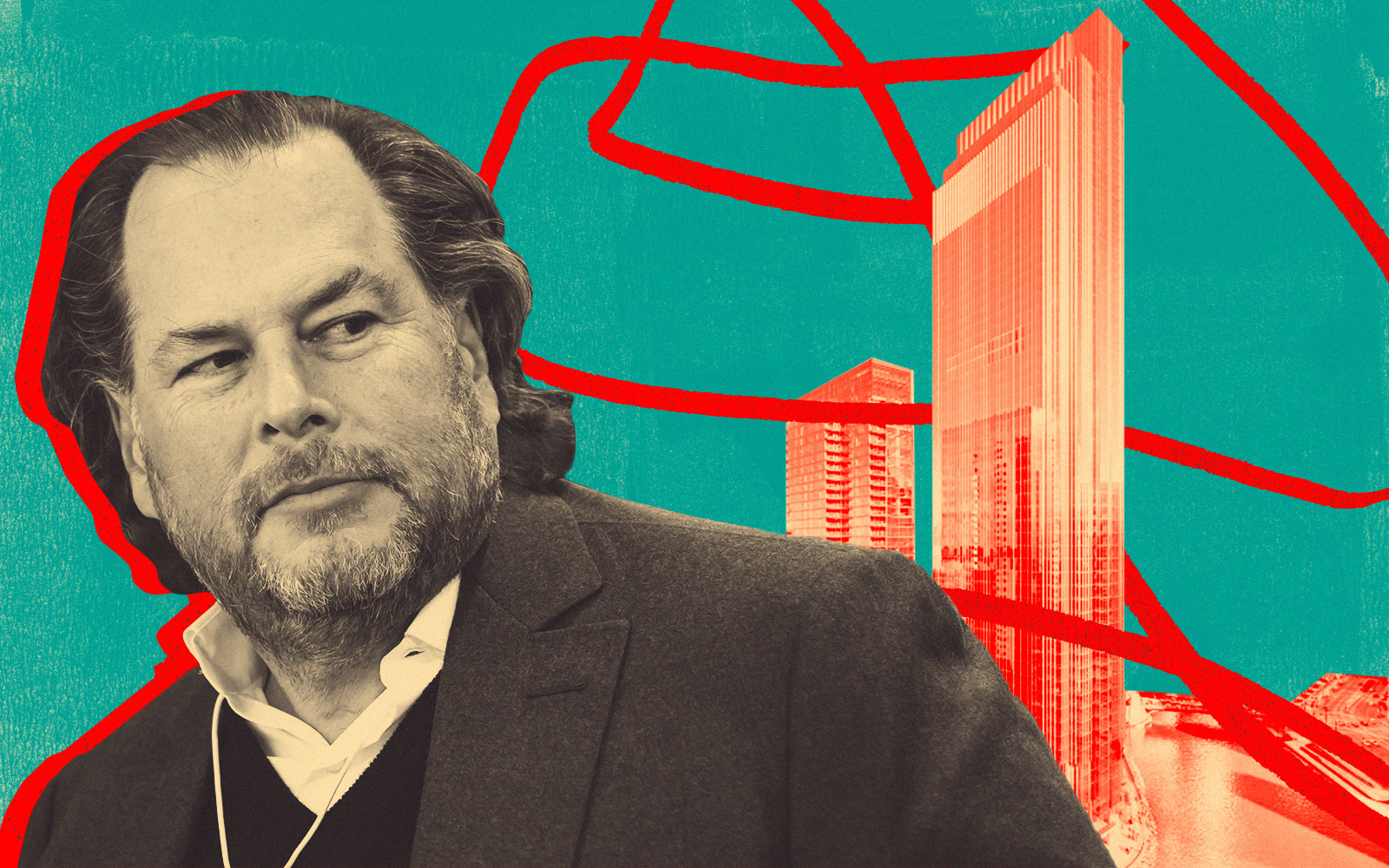

Salesforce is offering 100,000 square feet to tenants scouring the sublease market before the firm has even fully moved into the 500,000-square-foot lease it committed to Hines’ newly built Wolf Point tower. Meta is looking for a tenant to take 115,000 square feet off its hands at the John Buck Company-owned 151 North Franklin Street. And Publicis Groupe put up the city’s biggest space for sublease with a listing totaling 350,000 square feet at the Leo Burnett building on Wacker Drive, a 50-story asset bought last year by Opal Holdings and Katherine Cartagena for $415 million.

But the rental recovery rate from a sublease in a brand new building such as the Salesforce tower is likely to be much better for a sublandlord, even within shouting distance of 100 percent of the full rate paid by the original tenant to the building owner, brokers said.

“I can’t tell you it’s the most uplifting story when you keep hearing these large, large blocks of space are coming online,” Feinberg said. “For my clients, it’s phenomenal for those out there looking for space. But as a Chicagoan, it’s hard to watch companies moving from the city or saying we’re going to have more people work from home.”

Read more