Situated near some of the most valuable real estate in the world, Riverside provides a stark contrast to the Hamptons. This unincorporated hamlet, which is located within the Township of Southampton, is the most economically depressed part of Long Island. Downtown Riverside is known for flagrant prostitution and drug dealing amid a landscape of vacant buildings.

The hamlet wasn’t always a forgotten corner of the East End. In the 1940s and 1950s, residents say, it was a thriving working-class community supported by small family-owned businesses in construction, farming, trucking and the like. Then in the 1960s and 1970s, things took a turn for the worse, as they did in so many American cities. Many family-owned businesses found that they couldn’t compete with the new big-box stores. Riverside became a transit point for New York City’s drug market.

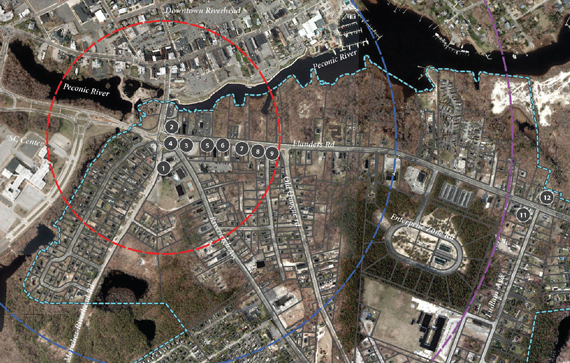

Now, after decades of neglect, Riverside is on the verge of an ambitious, mixed-use revitalization effort to redevelop 468 acres. The necessary rezoning of the land was unanimously approved by the Township of Southampton in late 2015, following years of planning and discussion. The revitalization effort aims to create jobs and generate tax revenue by transforming land now occupied by empty industrial buildings and other structures into nearly 2,300 housing units — including affordable housing — over 133,000 square feet of retail space and 62,000 square feet of professional offices. Other potential intriguing uses are under consideration, such as museums and nursing facilities.

“I can’t think of anywhere that needs it — or deserves it — more than Riverside,” said Sean McLean, the vice president of development and planning for Renaissance Downtowns, the Long Island developer in charge of the redevelopment plan.

Mastering the plan

“I look at this project as a rebirth, bringing back the community to where it was,” Riverside resident Robert Brown said at an upbeat community meeting to discuss the redevelopment plan in October 2015.

Yet the community may have to wait at least two years before construction can begin. The redevelopment plan is still under review by local authorities, and obstacles loom — not least, the need to create a new and expensive sewage treatment plant to support the projected new residents and businesses that redevelopment would bring to Riverside. Until work on the necessary sewage plant is underway, it may be difficult to raise financing for the redevelopment project, McLean said.

Yet the community may have to wait at least two years before construction can begin. The redevelopment plan is still under review by local authorities, and obstacles loom — not least, the need to create a new and expensive sewage treatment plant to support the projected new residents and businesses that redevelopment would bring to Riverside. Until work on the necessary sewage plant is underway, it may be difficult to raise financing for the redevelopment project, McLean said.

Once the shovels are in the ground, the redevelopment plan is projected to take 10 to 12 years to complete.

The hamlet’s needs are great. Riverside is the “single most economically distressed community” on all of Long Island, according to the Riverside Revitalization Action Plan. The hamlet has roughly 3,000 residents, about half of whom are white, with the other half roughly evenly divided between those describing themselves as Hispanic or black in the recent census. As of 2014, Riverside’s median household income stood at $53,250, with 42 percent of the population making $35,000 or less and a further 15 percent unemployed. One-quarter of the households were struggling below the poverty line.

To help pay for the sewage plant, Southampton recently applied to New York State for a $10 million grant. Town officials are also exploring ways to work collaboratively with the neighboring town of Riverhead, which owns and operates a wastewater treatment facility that may have enough capacity to support some of Riverside’s needs.

McLean acknowledged that sewers are the project’s biggest obstacle but said he’s confident the issue will be resolved. McLean added that he’s very open to the idea of building either a private treatment plant or opting for a public/private partnership.

Riverside scored a big infrastructure win in early June when Suffolk County legislators voted overwhelmingly in favor of budgeting $4 million to fund improvements to a traffic circle located within the heart of Riverside. Construction on the traffic circle, seen as a vital step toward the redevelopment effort, is expected to begin either in the fall of 2016 or in early 2017.

Beyond the infrastructure challenges, Riverside is still grappling with a serious crime problem. Despite the hamlet’s proximity to tremendous wealth, it has long been known for its open-air drug markets, prostitution and other criminal elements. In 2014, the most recent data available, there were 18 robberies, 28 aggravated assaults and 63 motor vehicle thefts in the communities of Riverside and neighboring Flanders. All represented an increase over the previous year, according to the Southampton Police Department. In the same year, there were 52 drug-related arrests, which is high for an area with a relatively small population.

“Crime is one of the cancers that affects a community that suffers from low socioeconomic conditions,” said Francis Zappone, deputy supervisor of the Township of Southampton and one of the leaders of the redevelopment effort. But he said there has been a slight improvement in criminal statistics in 2016, which he credits to residents being energized by the prospect of the redevelopment plan. “The community is starting to sense that something good is happening,” Zappone said.

Local law enforcement has done its part to tamp down on crime by bringing in officers from neighboring police forces as part of Suffolk County’s East End Drug Task Force. At the same time, Riverside is trying to start a local chapter of the Council of Thought and Action, known as COTA, a grass roots anti-recidivism movement.

“The capital markets don’t always trust that change is coming. That’s why it’s important to demonstrate that change really is coming,” said McLean.

Spurring new deals

Despite the challenges posed to this long-term redevelopment plan, it is being credited with helping to jump start the once-moribund local real estate market.

Since the beginning of 2016, six major properties totaling nearly 20 acres have sold or are under contract to sell to developers and investors, according to McLean. He said all of the properties were unoccupied and had been offered for sale for at least a decade. The properties ranged from an old Howard Johnson to a boarded-up dollar store, a closed gas station and several crumbling industrial buildings.

“Since the beginning of the year, people have started to buy these properties because they feel they are finally worth what the sellers are asking,” McLean said. He credits the approval of the zoning required for the redevelopment plan in late 2015 for sparking this local real estate revival.

McLean said that the new owners of these properties were considering them for a wide array of potential uses, including new mixed-use developments with apartments and storefronts, a hotel, several museum concepts and a nursing facility.

Market experts say that the flurry of sales activity is a sign of confidence in the revitalization efforts. Renaissance is working on six different site plans with the buyers of those properties to ready them for local approval. Renaissance is also working with several African-American families who have owned land in Riverside for generations and who wish to develop their properties.

“Nothing really good has ever happened to Riverside. It’s been in a cycle of disinvestment for so long,” McLean said. He said that Renaissance is also trying to recruit businesses to occupy existing space, including a building along the river that has sat on the market for years.

Housing for workers

The redevelopment plan requires half of the multi-family housing to be “community benefit housing.” This includes workforce housing with pricing based on income, and that gives priority to veterans, town employees, existing residents of the school district, emergency medical services volunteers, firefighters and others. A portion of the affordable housing is slated for rental, and the rest will be condominiums for sale. An assisted-living center with below-market rates is also under consideration.

Zappone points out that there is a great need to provide housing options for Long Island’s young residents. “We don’t want young men and women who reach their twenties and thirties to return and say, ‘Gee, there isn’t any reason for me to live in this community anymore,’” he said. “We’ve got to address that socioeconomic change.”

Vince Taldone, a local activist involved with the redevelopment planning process, said that providing affordable housing for workers was a key provision of this plan. “Even if you get a halfway decent job out here, there’s nowhere to live,” he said. “Housing prices are impossible.”

Although some locals have expressed concerns about the strains that the increased traffic and the number of school-age children from the new development would put on the hamlet, most residents expressed a positive attitude to the plan at community meetings.

Taldone, who currently serves as treasurer of the Flanders, Riverside & Northampton Community Association, credits the community support to the developer’s use of “crowdsourced placemaking,” a trendy term in the building trade to describe a process that is open to the community through live and online forums. Renaissance has hired a multilingual community organizer to reach locals who don’t have Internet access.

“We didn’t feel like people were doing something to us,” Taldone said. “We were participating.”