Madison Realty Capital, a private real estate investment firm heavily backed by public pension money, has been stuck with a nearly half-empty rental portfolio in Manhattan’s East Village.

When the New York-based firm financed controversial landlord Raphael Toledano’s purchase of the 16 buildings in 2015, critics called the deal overleveraged. Madison lent $124 million for a portfolio that cost $97 million.

But the lender had its reasons.

The firm, led by Josh Zegen, Brian Shatz and Adam Tantleff, had just landed a $100 million commitment from the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, which manages a $122.5 billion pension fund. And the pressure was on: If the landlord failed to renovate and convert a bunch of its 226 rent-stabilized units to market-rate, he would be unable to make his loan payments.

Of course, Toledano did fail. Low-rent tenants moved out, but renovations went unfinished — rendering many apartments unlivable. Now, the East Village portfolio is mired in bankruptcy proceedings that have dragged on since 2017, impacting all parties that invested.

“The owner of the properties demolished the vacant units a few years ago, and therefore the vacant units are not habitable at this time,” a spokesperson for Madison told The Real Deal, noting that the company still does not own them.

Toledano and his attorney declined to comment.

More than half a year since New York overhauled its rent law, multifamily landlords and their lenders — from family-run firms and local banks to larger institutional players — have been feeling the heat. But another significant group of investors is exposed to the new rent regime: public school teachers, firefighters and other state employees.

Four of the largest public pension systems in New York and California committed more than $30 billion to private real estate funds held by Brookfield Asset Management, Blackstone Group, Apollo Global Management and the Carlyle Group, according to the pension funds’ annual financial statements.

Nearly all of those private equity giants have made big investments in rent-regulated multifamily properties in recent years.

Nearly all of those private equity giants have made big investments in rent-regulated multifamily properties in recent years.

Madison, a smaller fish by comparison, has also touted its appeal to public pension funds and other institutional investors with “superior risk-adjusted returns.”

Such pitches are often made by placement agents who try to persuade pension funds to invest billions of dollars in real estate and other assets, according to several insiders. And while the funds almost never oversee the management of properties, in many cases, the returns they are seeking can drive speculative bets.

The top priority for public pension funds, of course, is to deliver the best returns to those who put their future retirement savings on the line. But since elected officials often use them to advance social causes, such as poverty reduction and affordable housing, being associated with driving out rent-regulated tenants can create more than a few public-image concerns.

Tom Hester, a managing director on the real estate team at advisory firm StepStone — which has received $200 million in commitments from the New York State teachers’ fund and consults on the retirement system’s investments — said the stakes are high for pension funds that pour money into rent-stabilized housing in today’s political environment.

Many are becoming all the more cautious when investing in cities like New York and San Francisco to avoid getting tangled up in “the business of having to evict someone,” Hester said.

Fund frenzy

Overall, pension funds are investing more aggressively in real estate as they look further beyond the stock market and fixed-income investments.

“Real estate still provides an outsize return over other asset classes,” said Jeffrey Scott, who runs the commercial brokerage Eastdil Secured’s New York City office.

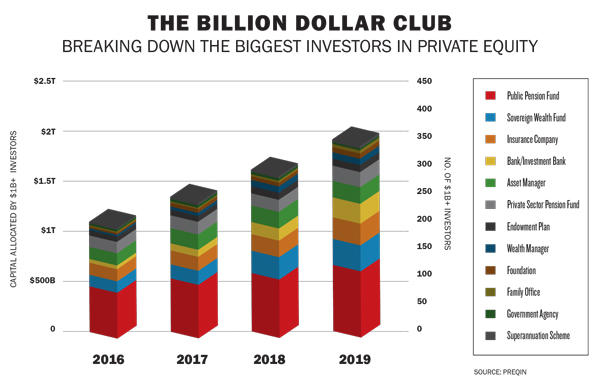

In 2019, public pension funds in the “billion dollar club” — a list of 412 of the world’s largest investors tracked by private equity research firm Preqin — were the largest single source of funding for private equity firms.

Public pension funds provided a total of $704 billion to private equity, according to Preqin. The next largest source of capital, sovereign wealth funds, provided $272 billion.

“Pensions are what really drive the market at the end of the day. Their appetite or lack thereof determines a lot of transactions,” Scott noted.

And with interest rates close to rock bottom, pension funds are keeping their return expectations high, said Savills’ chief economist Heidi Learner, who added that many are targeting returns of 7 percent or higher. As a result, she noted, some are going to have to up their bets on real estate and other alternative investments to meet those goals.

The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) has shown a particularly strong interest in real estate and now has nearly $35 billion invested in property around the country. After years of exceeding its real estate target allocation of 13 percent, in its January board meeting, the state pension fund solidified a plan to increase that figure to 15 percent, from which it expects a 6.3 percent return.

LCOR, a New York-based development firm controlled by the California teachers’ pension since 2012, backed a deal in January to build a large apartment building on Coney Island from the ground up. The company signed a 99-year ground lease to take over a nearly full-block parking lot on Surf Avenue that allows for about 325,000 buildable square feet.

“We are currently in the initial planning stages and anticipate a mixed-income residential development with up to 30 percent of the apartments designated as affordable,” LCOR’s senior vice president, Anthony Tortora, told TRD at the time.

While pension money has been present in New York City real estate for years — especially large office towers, rental buildings and other cash-flowing assets — it’s less common in ground-up development, which carries its own risks.

Unusual in this case is CalSTRS’ role as a partner in the development venture rather than providing capital to an outside adviser like Morgan Stanley to invest the capital, said Jeffrey Julien, a managing director in JLL’s New York office.

“Pension funds are looking to development, taking on the risk and having a higher yield on investment,” said Julien, who was part of the brokerage team that arranged the financing for the Coney Island ground lease deal.

He added that pension funds and other institutional investors, wary of the regulatory changes taking place in New York, have become more interested in funding ground-up developments covered by the state’s tax incentive program dubbed Affordable New York.

But Eric Anton, a veteran investment sales broker who leads Marcus & Millichap’s capital markets group in New York, underscored the preference among many pension funds to keep a low profile. While funds are upping their investments in real estate, they’re also keenly aware of their fiduciary responsibility and mandate for social responsibility, he noted.

“The pensions are extremely important, but it’s quiet,” Anton said. “These are the kind of people who pay publicists to stay out of the newspaper.”

A deal undone

In less than two years, Toledano’s East Village deal went bad and Madison moved to foreclose on the landlord’s firm Brookhill Properties.

But the 2017 bankruptcy proceeding came amid accusations that the lender had demanded returns that were impossible to deliver without aggressive management tactics — a move that carried both financial and reputational consequences.

Then-Attorney General Eric Schneiderman lambasted Madison’s strategy, pointing to an investor memo that stated Toledano planned to vacate, renovate and deregulate nearly half of the 279 units in the portfolio within the first two years. In some of the buildings, the required turnover rate was as high as 80 to 100 percent.

“Tenant advocates argue that landlords displace tenants,” one multifamily owner said on the condition of anonymity, “when their investors are the ones telling them to clear people out and raise the rents.”

A 2015 investor pitch to the Public Employees Retirement Association of New Mexico, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, shows Madison promoted returns of more than 9 percent over the benchmark S&P U.S. Leveraged Loan Index.

Madison did not comment on its pension fund holdings or the promises it made to its investors.

Aggressive investment strategies can sometimes lead to the blacklisting of some investment firms, according to Doug Weill, founder and co-managing partner at the real estate advisory firm Hodes Weill.

“There are numerous examples of pension money managers that had spectacular falls from grace,” he said. “They just kind of withered away as their clients abandoned them on future fund raises.”

One of the most notable “falls from grace,” he noted, was Broadway Partners, which made a series of high-profile acquisitions ahead of the financial crisis, flush with money from institutional investors that included pensions. After the crisis, the company defaulted on several properties and was forced to sell off the majority of its portfolio.

But that has yet to happen in Madison’s case.

The New York State teachers still have a stake in the firm’s debt deals, according to the pension fund’s most recent annual report (but that doesn’t show how that investment is performing).

The decision to invest with Madison never came up for a vote in the organization’s headquarters on the outskirts of Albany, where its board meets four times each year in a chamber behind tinted glass.

A spokesperson for NYSTRS said its $100 million commitment to Madison’s fund “did not require additional or secondary approval at a board meeting” because it did not exceed the pension fund’s limit on single investments — so it was rubber-stamped without a vote.

Last November, the Texas Municipal Retirement System made its own $100 million commitment to one of Madison’s four debt funds, which have raised more than $2.8 billion to date. Nick O’Keefe, lead investment attorney at the statewide retirement system, said a Texas statute that exempts private equity investments from the Freedom of Information law makes the state more attractive to firms like Madison.

“They say, ‘It’s more appealing for us, because you’ll protect our information,’” O’Keefe, told TRD. “There’s a certain amount of truth to it.”

But that can cause even bigger headaches when the information surfaces. Apart from the negative headlines, public pension funds are wary of being perceived as “taking fiduciary risks with other people’s money,” StepStone’s Hester noted.

“You don’t want a situation where you’re seen as gambling when the reason you exist is to put bread and milk on the table of pensioners,” he said.

The big pitch

When Blackstone’s Stephen Schwarzman opened his firm’s third quarter earnings call, he had a clear message for investors: The private equity giant’s holdings — including more than $320 billion in real estate — provide returns to public pension funds that are unattainable in fixed-income investments.

“The very strong returns we generate, particularly in the current low-interest rate environment, enable teachers, police officers, firemen and other public and corporate sector employees to retire with sufficient savings and secure pensions,” Schwarzman said.

Among public pension-backed private equity firms, Blackstone leads the pack with more than $9.7 billion in commitments, investments and assets under management from seven leading public pension funds in New York and California, according to the funds’ annual financial reports.

That includes the New York State Common Retirement Fund, which has $207.4 billion in assets under management, including $3.6 billion invested with Blackstone, records show, and the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), which manages $396.9 billion and has $2.7 billion invested with Blackstone.

Those investments have helped to fuel some of the world’s largest commercial real estate plays, including Blackstone’s $18.7 billion purchase of GLP’s industrial warehouse portfolio last year and the firm’s $5.3 billion purchase, with Ivanhoé Cambridge, of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village in 2015. Ivanhoé Cambridge is a subsidiary of Canada’s second-biggest pension fund.

Blackstone and the New York State retirement fund declined to comment. CalPERS confirmed its totals but would not discuss further.

In New York, California and other states, public pensions are mandated to pay workers’ retirements based on an equation that was set when they were first hired — putting pressure on the funds to make lucrative investments.

The message wasn’t lost on Tom Bannon, who oversees the California Apartment Association, the state’s most influential real estate trade association.

Bannon told TRD in October that the calls for rent control in California may have been tempered by the state’s public pension money invested in private equity firms who generate returns for their government investors through real estate ventures.

State politicians were aware that a stricter form of rent control would “literally shut down the California economic machine,” said Bannon, who also noted that “Blackstone is where CalPERS and CalSTRS invest their money.”

Pensive plays

During a CalPERS’ investment committee meeting last year, Ben Meng, the agency’s chief investment officer, outlined a plan to meet the fund’s obligations to pensioners.

“We need private equity, we need more of it, and we need it now,” Meng said.

At the same time, private equity firms often hire placement agents and other advisers who promote real estate assets to pension funds as a safe bet.

While placement agents have been banned in some states within the past decade, they still play a big role in pension investment strategies as a whole. In 2010 — after a series of pay-to-play scandals involving elected officials steering public pension fund investments to firms — New York, Illinois and New Mexico outlawed the use of such intermediaries.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission then implemented new rules to curtail the influence of pay-to-play practices by investment advisers.

But California has no such bans. Instead, placement agents are required to register as lobbyists with the state.

In other states, like New York, commercial real estate brokers and other investment advisers are still fair game as long as they don’t make or bundle campaign contributions to politicians who could influence the selection of the adviser.

And since most public pension funds don’t have in-house real estate teams to guide their investing, that task is still largely outsourced to firms with the expertise to hunt down deals.

“It’s the adviser guiding the pension fund, whether they have full discretion or not,” said Adam Steinberg, a principal at Ackman-Ziff Real Estate Group who co-heads the brokerage’s equity business. “If the recommended investments go well, they should maintain their current role and could even get a greater allocation [to advise on] — so the stakes are high.”

But Eileen Appelbaum, an economist and author who researches private equity, said the deals negotiated between advisers and pension fund managers have become an even bigger cause for concern in recent years.

“There is a conflict,” she said, “because at some point in the not too distant past, we allowed pension funds to make risky investments as long as the risk is balanced in the overall portfolio.”

That risk-reward tradeoff is becoming increasingly visible to tenants, sources say.

Jim Markowich, who lived in one of Toledano’s East Village rentals, argued that the potential returns for pension fund investors like the New York State teachers do not outweigh the potential harms to those who are evicted from their apartments.

“The goal is to make double digit returns for investors,” Markowich said. “It all makes sense except it does it at the expense of people trying to live in their own homes, which is really hard to justify.”