Three of Petra Drauschak’s 14 tenants have abandoned their leases during the pandemic.

One had already stopped paying by February 2020, when Covid began sweeping across the U.S., but Drauschak’s hands were tied by Pennsylvania’s eviction ban. The tenant left in August without paying the remaining rent and arrears.

Tipped off by a neighbor, Drauschak followed the tenant to her ex-fiance’s house and successfully served her papers. A court awarded the landlord $12,000, but the tenant disappeared without settling the debt. Drauschak’s legal costs were $600.

The second tenant stopped paying when federal rental assistance became available in June. After Drauschak filed for an eviction, the renter applied for federal rent relief, and Drauschak was made whole with a check for $5,800.

The third tenant did not qualify for federal relief because undocumented immigrants are not eligible. Upon losing work at a landscaping company, the tenant was unable to pay rent for four months and was asked to leave.

“I said, ‘Listen, I can’t do this, this is a business,’” Drauschak recalled. It took her four more months to find a paying tenant.

“A lot of [undocumented people] are in a really tough position,” said Drauschak. “These people are truly screwed.”

With the pandemic causing billions of dollars in unpaid rent to pile up and sapping demand for rentals, a new dynamic has emerged between millions of tenants and their landlords.

Eviction bans and the weakening of the rental market have made landlords less inclined to play hardball when tenants miss payments or skip out on leases. But tenants face deterrents as well. Failure to pay can lead to legal troubles and garnished wages years later, not to mention lower credit scores and rejected applications for housing.

Peter Von Der Ahe, a top multifamily broker at Marcus & Millichap, said the unpaid rent will follow tenants long after they have given back the keys.

Peter Von Der Ahe, a top multifamily broker at Marcus & Millichap, said the unpaid rent will follow tenants long after they have given back the keys.

“If you sign a lease and don’t pay it, it’s like a telephone bill,” said Von Der Ahe. “Verizon will eventually find you, and you’ll have to pay it or you’ll never have a cellphone again.”

High stakes

Landlords who go after tenants for unpaid rent run the risk of incurring legal fees to win judgments that cannot be collected. Collection efforts can even trigger lawsuits against the property owner.

In a case this month, five renters at a Carnegie Management building in Bushwick sued the Brooklyn-based landlord, alleging it inflated the rental arrears it reported to collection agencies.

Dinging tenants’ credit for unpaid rent is not new, but the lawsuit claimed Carnegie had added late fees, violating a ban put in place by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo for the first six months of the pandemic. The tenants argued the fees were a punishment for organizing.

Carnegie Management principal Isaac Jacobowitz said his firm engaged the collection agency just as “any utility company” would for customers who skip payments. The strategy worked to recover rent in most cases, Jacobowitz said, because tenants do not want their unpaid balances reported to credit bureaus.

“People shouldn’t be left without a house,” Jacobowitz said. “But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have to pay.”

Another option for landlords is using the security deposit to cover unpaid rent, but that has its drawbacks. Typically, it is only one month’s rent, so it is quickly exhausted, leaving the landlord less recourse if the tenant damages the apartment or exits with unpaid rent.

Tapping security deposits can also spur tenants to file a complaint.

One who lived in one of Steve Croman’s East Village apartment buildings said the landlord did not return full security deposits to many who moved out during Covid.

She said the third-party company that manages the buildings “whittled down” her $3,995 security deposit to $1,645 for things like “teeny-tiny” nail holes — and then failed to return even the smaller amount after she moved out in April.

Speaking anonymously because the case is ongoing, the tenant said she and some of her former neighbors filed a complaint with New York Attorney General Letitia James. No money has been recovered. The management firm, an affiliate of Besen Partners, did not return a request for comment.

Eviction-proof tenants

Camden Property Trust, a real estate investment trust that controls nearly 60,000 apartments across the country, reported that revenue from its more than 2,100 apartments in Los Angeles and Orange counties was down 5 percent year-over-year in the fourth quarter. Annual revenue fell more than 13 percent from the year before.

The problem, Camden CEO Ric Campo said, was not that tenants could not pay, but that they chose not to, taking advantage of eviction moratoriums and inspired by the “cancel rent” movement.

“They look at it as a free loan from Camden,” said Campo. ”But ultimately, they will have to pay or their credit will be destroyed.”

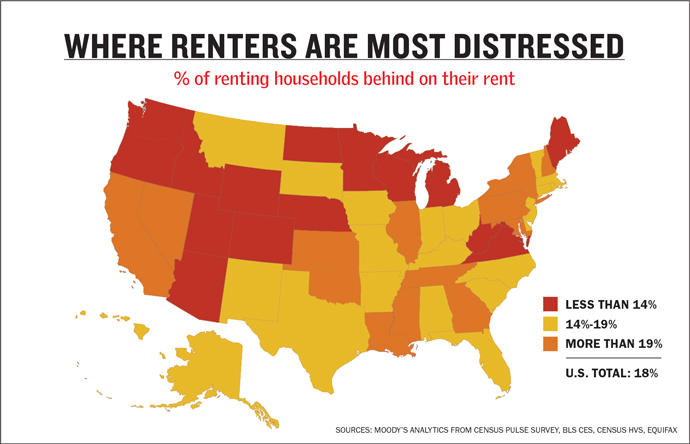

Most tenants, especially in market-rate apartments, have continued to pay rent. But financial problems have mounted for workers in industries hardest hit by the pandemic. In July, four months after shutdowns began, an advisory firm’s study calculated rent arrears at $21 billion nationally. As of January, Moody’s expected the number to be $57 billion, including utilities and late fees — an average of $5,600 across approximately 10 million delinquent households.

Those who don’t pay face a reckoning. Landlords in New York have six years to sue for back rent, said Shanna Tallarico, a consumer debt attorney at New York Legal Assistance Group. But she does not expect them to wait that long.

“Everyone is anticipating this flood of cases,” said Tallarico. “We are going to get so many calls soon — I can’t even fathom what it will look like in a year from now.”

One client, a tenant receiving federal Section 8 benefits, left her Bronx apartment in 2016 and relocated to North Carolina. In 2019, her bank account was suddenly frozen because of a default judgment won by her landlord, Genesis Realty Group, which filed a case more than two years after she moved out.

One client, a tenant receiving federal Section 8 benefits, left her Bronx apartment in 2016 and relocated to North Carolina. In 2019, her bank account was suddenly frozen because of a default judgment won by her landlord, Genesis Realty Group, which filed a case more than two years after she moved out.

In March, the tenant drove to New York City to appear in court. One week before the courts shut down for Covid, a judge canceled the judgment. The case is now one of many in limbo as courts work through their backlogs.

No Covid discount

Suzanne Pichulik Eisenberg, a landlord in Decatur, Georgia, said she’s not negotiating a “Covid discount” with her tenants, and none has walked away yet. “I just wasn’t going to negotiate based on an anomaly,” said Eisenberg, who renewed leases at current levels. With vacations canceled, fewer date nights and no babysitting expenses, she is hoping her tenants are saving money for future increases.

Owners in her state have greater leverage than they do in New York. “It’s very different in Georgia,” Eisenberg noted, “because it is more landlord-friendly than tenant-friendly.”

In New York City, political victories by tenant advocacy groups and the pandemic-driven drop in demand for rentals have strengthened tenants’ hand. The state’s rent stabilization law enacted in 2019 increased penalties for rent overcharges, severely limited rent increases and took steps to eliminate the so-called tenant blacklist — Housing Court records used by landlords to screen applicants for apartments.

Adam Mermelstein, whose Treetop Development has 1,500 rent-stabilized units in the city, says the tenant movement’s gains have empowered renters to walk away from their agreements.

“We do find in New York City people break leases more so than in other places,” he said. “Up until recently that hasn’t been a problem, because rents always went up. But now when the tenant breaks the lease, it’s a big deal.”

Before Covid and the new rent law, owners of the city’s 900,000-plus rent-stabilized apartments relished vacancies because they allowed landlords to raise the rent up to 20 percent in a market with robust demand.

With those factors gone and Covid lingering, waging a legal battle with a tenant isn’t always worth it. In many cases, Mermelstein said, it’s better to negotiate a rent reduction, or let the tenant leave without paying all the remaining rent.

“More often than not, we work something out,” the landlord said. “We have to pick our battles.”