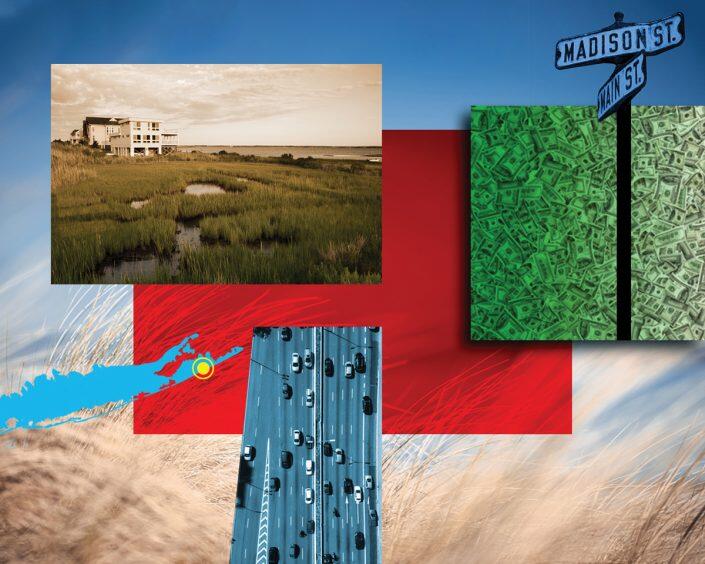

As $812 million mansions are snapped up by financiers as fast as they can be built and it’s hard to find a seat on a helicopter trip to the Hamptons, the people who build the houses there leave in pickups and vans around 4 p.m. each day. The road out is bumper-to-bumper.

As $812 million mansions are snapped up by financiers as fast as they can be built and it’s hard to find a seat on a helicopter trip to the Hamptons, the people who build the houses there leave in pickups and vans around 4 p.m. each day. The road out is bumper-to-bumper.

The trade parade, as it’s called, exists because most workers cannot afford a home in the area. In 2020, its median home price was $920,500, according to Miller Samuel. In all of Suffolk County, it was $402,000.

Why don’t blue-collar folks rent instead? If only.

Year-round rentals have become increasingly scarce because landlords east of the Shinnecock Canal can profit more by renting for just the summer. Add in the rise of sites such as Vrbo and Airbnb — and pandemic relocations — and the result for tenants is that 12-month rentals are like gold dust.

Instead, skilled tradespeople must commute from Riverhead or even Brookhaven, causing traffic and stress for everyone. Meanwhile, a close-knit community of middle-class locals is being lost.

Even for professionals with healthy incomes, the problem is acute. Take Chimene Macnaughton, a hospitality executive, and her husband, Craig, who has a photo business. “I’ve lived out east full-time for 17 years,” Macnaughton said. “Originally, I paid $300 a month for a quarter-share winter rental in East Hampton. Now, my husband and I pay $2,750 per month, plus utilities, for 1,250 square feet.”

And that’s the good news. The bad: Staying could cost them more than twice that.

“We have to move. Our lease has ended, and our landlord wants to jack up the rent, but we haven’t even found a whisper of anything under $6,000 per month for year-round,” Macnaughton said. “And a lot of these are former summer homes, poorly insulated, with electric heat.”

The fall should bring renters some respite. “We’re just now starting to see post-Labor Day availability that starts with a 4,” said Macnaughton, who called $4,500 “bare-bones entry level” for what cost $2,000 pre-pandemic. But hanging on until then presents another challenge.

“When we signed our standard two-year lease in early 2019, we thought nothing of the fine-print, $500-a-day holdover clause,” she said. “Well, our landlord is attempting to enforce it.” That debt is up to $32,500. Without eviction moratoriums, the couple might have been sent packing by now, despite staying current on their regular rent.

Buying is not a great option either, as home prices have soared. “The pandemic has accelerated trends that were already in motion, and affordable housing and finding employees on the South Fork is certainly one of them,” said Assembly member Fred Thiele, a Southampton native.

“Inventory for people who live or work in the community who might want to rent or buy a year-round home is lower, and buying is a lot harder,” the 67-year-old lawmaker said. “Pre-pandemic, affordable housing was a severe problem. Now, I would say it’s a crisis.”

Another issue for Hamptons workers is their commute. “I see lack of both housing and public transportation hand-in-hand because people who can’t afford to live here live further to the west and they have to drive here for their jobs in the morning,” Thiele said. “Nobody wants to sit in traffic for a couple hours every morning to get to their job.”

Thiele has been working to increase affordability, but it has been far more difficult than establishing the Community Preservation Fund, which he introduced in 1998. As he points out, it’s easy to find people who want open space, but not everyone wants affordable housing next door.

However, given the pandemic’s effect, more people now see something needs to be done. Thiele calls community housing the open-space fund’s “little sister.”

The 2 percent tax on East End land sales that feeds the fund has likely made housing more expensive by limiting the supply, but soon a new law could promote affordability.

A bill that awaits the governor’s signature would let the towns of East Hampton, Riverhead, Shelter Island, Southampton and Southold establish community-housing funds to aid the development of affordable housing for sale and rent, the rehab of buildings for community housing and the acquisition of existing housing.

Income-eligible residents and local employees who are first-time homebuyers could also get financial assistance from the fund for up to half the purchase price.

“This law is one just tool that we need for affordable housing here,” Thiele said. “I don’t see it, by itself, as a silver bullet. I still think we need to do more. There’s a lot of interest in what the state can do to incentivize accessory apartments.”

Paul Monte, president of the Montauk Chamber of Commerce, said another issue is seasonal workforce housing, particularly in Montauk, the most summer-based economy on the East End. He said that East Hampton Town has done a lot to help with affordable housing, but “there has been no attempt at all to do anything of substance to solve our seasonal housing issue. Many people will say, well, that’s a problem that the businesses have to solve on their own because they’re the ones that are benefiting from the seasonal employees.”

The biggest obstacle to creating such housing, Monte said, is zoning and wastewater issues, which employers cannot overcome by writing checks. “If the town and the county worked together with the business community, that problem could be alleviated to a large degree,” he said.

Seasonal housing could be dormitory buildings, mobile homes or tiny homes, perhaps on commercial properties.

Why isn’t this done today? Monte says, “It’s a legislatively created obstacle, which was done for certain reasons, but the fact is we cannot now have more than four unrelated people in a rented home unless the owner of the home lives there also.” New York City has a similar law, written ages ago to ban boarding houses.

“There’s no reason,” Monte said, “why a four-bedroom, five-bedroom house couldn’t have eight or 10 occupants, two people to a bedroom, and to be able to accommodate them comfortably and efficiently and safely.” Back in the day, business owners would rent a place for employees to do just that, but they can’t any longer, legally or financially. Most local businesses are small and have limited resources.

Dr. George Dempsey, an East Hampton general practitioner, has seen his practice grow in the past year with more new patients from New York City and more year-rounders. He’s added employees, but local housing for his nurses, receptionists and other support staff is out of reach. Many of them endure long commutes.

“People are coming out here to work despite all the obstacles, because rates of pay are so much higher,” he said. “But they have to sit in two hours of traffic just to get to work.”

Dempsey thinks the community needs thousands more units, which he said would require looser restrictions on accessory apartments, among other changes.

“I’d like to see increased density in the villages. Senior housing would be great in downtown East Hampton, so seniors could walk around the village and be part of the community,” he said. “The community that we had here for hundreds of years is rapidly just disappearing.”