Standing in front of a mostly virtual audience in a fitted dark suit with slicked-back salt-and-pepper hair, Brian Kingston attempted to calm investors’ nerves about the coronavirus’ impact on real estate.

“Ultimately, this is temporary,” the CEO of Brookfield Property Partners said at the firm’s investor day in late September. “We will recover, we’ll come out the other side of it.”

The numbers were concerning: As of Sept. 18, only about 10 percent of Manhattan workers had returned to the office, according to CBRE. An August survey of hundreds of CEOs by KPMG showed that 69 percent of them planned to downsize their long-term space requirements. Brookfield Property Partners is among New York City’s largest office landlords — it controls about 27 million square feet in the city —and is in the midst of building an office megacomplex known as Manhattan West.

The company’s U.S. retail portfolio — a mall-heavy 120 million square feet — was also coming under stress. Just days before the investor conference, the firm told employees it was cutting roughly 20 percent of its retail staff and suggested it would shed some of its assets.

While most retail and office landlords have been hit by the coronavirus, Brookfield Property Partners has far more leverage than its American peers. But as a Canadian company, it can value its assets differently.

At the heart of these differences is the company’s accounting. Unlike its American rivals, who report under GAAP, Brookfield Property Partners uses IFRS, an accounting standard commonly used by foreign companies. Under IFRS, the company has greater discretion over its real estate asset valuations — it does not have to base its valuations on independent third-party appraisals and can instead devise them based on internal assessments. To put it simply: The listed values of its properties may not reflect current market conditions if Brookfield’s leaders choose not to sufficiently adjust them.

In a rising market, those distinctions may not matter. But given that the company collected just about 35 percent of its retail rents in the second quarter and long-term office occupancy is in flux, the question becomes: Does Brookfield’s balance sheet fully reveal the health of its assets?

We the North

Brookfield declined to make executives available for an interview, but provided written responses to The Real Deal’s questions.

Brookfield declined to make executives available for an interview, but provided written responses to The Real Deal’s questions.

Brookfield Property Partners is one of the largest commercial landlords in the U.S., but its roots are deeply Canadian. Edper Investments, precursor to Brookfield Property Partners’ parent company Brookfield Asset Management (BAM), was founded by members of the Bronfman family of the Seagram liquor fortune.

This Canadian pedigree gives the firm a competitive advantage over local U.S. real estate investors. IFRS allows Brookfield Property Partners to rely on its management’s own judgment.

“Even though you have a reasonable amount of discretion in the United States, you even have a hell of a lot more with IFRS,” said James Cox, a securities law expert at Duke University.

Under IFRS, Brookfield Property Partners does not need to turn to third parties to assess the value of its real estate assets. Instead, the company can base valuations on its internal assessments. Meanwhile, companies that report under GAAP usually base valuations on historical cost — i.e., how much the assets traded for.

Al Rosen, a Toronto-based forensic accountant who predicted the collapse of Canadian telecom giant Nortel Networks, likens IFRS to an 8-year-old preparing their own report card.

“The rules themselves allow you to pick the numbers,” said Rosen, speaking generally about IFRS and not specifically about Brookfield. “This bullshit does not get exposed enough in Canada.”

Brookfield Property Partners said it uses third-party appraisers to “compare the results of those external appraisals to our internally prepared values.”

And those numbers, according to the firm, match up pretty closely. In its most recent quarterly report, the company said it used external appraisals on 14 percent of its office portfolio, and that those appraisals were within 0.5 percent of management’s valuations. But there is no mention in the report of whether Brookfield conducted these appraisals for its retail portfolio. Retail was among the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic, and thus retail properties were at greater risk of losing value.

Over the years, BAM and its subsidiaries have faced scrutiny for how they value assets. Roddy Boyd at the Foundation of Financial Journalism first highlighted these issues in 2013. A September report by Dalrymple Finance, an investment firm run by short seller Keith Dalrymple, also flags some of these concerns.

Given the pandemic, some of Brookfield’s peers wrote down their asset values substantially.

A look at Brookfield Property Partners’ second-quarter financial statements, however, reveals that the company did not follow suit. (The company says its valuations are “compared to market data, third-party reports, research material and broker opinions” for Brookfield to review. )

Brookfield Property Partners’ joint venture in the Ala Moana Center, a 2.2 million-square-foot retail center in Honolulu, saw its carrying value decline just 3.75 percent to $1.87 billion in June from December. Hawaii’s tourism has fallen off dramatically since the state ordered mandatory quarantines for out-of-state travelers in March. Neiman Marcus, one of the center’s anchor tenants, filed a WARN notice Sept. 21 announcing plans for mass layoffs at the store and stated that “there is no realistic prospect for store revenues to recover to a sustainable level in the foreseeable future.”

Mahattan West

Some of Brookfield Property Partners’ valuations even went up during the height of the pandemic.

In Las Vegas — where the unemployment rate is above 15 percent and the Strip shut down for the first time since the JFK assassination in 1963 — the company reported increases in its carrying values of its retail properties. In the six-month period ending in June, its valuation of its stake in the Grand Canal Shoppes rose to $423 million from $414 million, while its stake in the Fashion Show Las Vegas shopping center also increased in value, to $846 million from $832 million.

A Brookfield spokesperson said the change in the Las Vegas valuations “was a result of several recently signed leases at above expected rents.”

Overall, Brookfield Property Partners claims that its “proportionate fair value” of its core retail properties declined by just 3.35 percent to $34 billion over the first half of 2020, according to the company’s second-quarter supplemental report.

Compare that to U.K. real estate REIT British Land, which also reports under IFRS and marked down its U.K.-centric retail portfolio by about 26 percent to 3.9 billion pounds. Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, a Paris-based mall conglomerate that uses IFRS, wrote down the valuations of its U.S. mall portfolio by about 5 percent.

“We have made substantial progress in reaching agreements with tenants in regards to their rental arrears, and current collection rates are materially higher,” a Brookfield spokesperson said of the health of its retail portfolio since its most recent filing.

In September, Kingston told financial news publication PERE that the dire prognostications about retail mirrored what was being said in 2010, when BAM invested in retailer General Growth Properties (GGP) to pull it out of bankruptcy. That bet, Kingston said, turned out to be lucrative.

“We’re looking at this period of time the same way,” he said. “There is clearly disruption happening in the market. But ultimately we take a long-term view that high-quality real estate assets will hold their value and recover when the economy recovers.”

Flatt out investing

Toronto-based BAM is a closely held conglomerate with interests in everything from railroads to hydroelectric dams to office buildings. With about $550 billion in assets under management, there are few companies with such resources, reach and power.

The SoNo Collection

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the company, then known as Edper, was led by Jack Cockwell, a tough South African-born accountant. Edper almost collapsed under its debt, but survived and expanded its real estate holdings by acquiring the assets of the failed Canadian conglomerate Olympia & York in the mid-1990s. Those properties included the World Financial Center in Lower Manhattan, later rebranded as Brookfield Place.

In 2002, Cockwell handed over the reins to Bruce Flatt, a fellow accountant from the Canadian province of Manitoba. That leadership transition marked the beginning of one of the world’s most aggressive investment sprees. A 2017 Forbes cover story described Flatt as the “Billionaire Toll Collector of the 21st Century.”

BAM and its subsidiaries are now among the world’s largest property owners. The investment giant has a major stake, along with the Qatar Investment Authority, in the Canary Wharf megadevelopment in London. (QIA is a substantial investor in Brookfield Property Partners, owning roughly 7 percent of the company as of the end of 2019, filings show. It is also a significant investor in the firm’s Manhattan West development, owning 44 percent.)

In 2018, Brookfield Property Partners acquired the rest of GGP for $9.25 billion in cash, making it one of the largest mall owners in the U.S. This August, Flatt disclosed that BAM had raised a record $23 billion in the second quarter, with over half of that earmarked for distressed-debt investing.

In New York, Brookfield is a commercial behemoth with a penchant for rescuing high-profile players from struggling projects: In April 2018, Brookfield Property Partners paid Somerset Partners and the Chetrit Group $165 million for a sprawling waterfront site in the South Bronx, a project for which the developers had struggled to land financing. A month later, BAM was in advanced talks to take over the ground lease at Kushner Companies’ albatross, a 41-story office and retail skyscraper at 666 Fifth Avenue; it closed on that transaction over the summer.

“We like them, we like their culture, it’s very similar to our company culture,” Charlie Kushner, founder of the firm, said of Brookfield in a 2018 interview with TRD.

All in the family

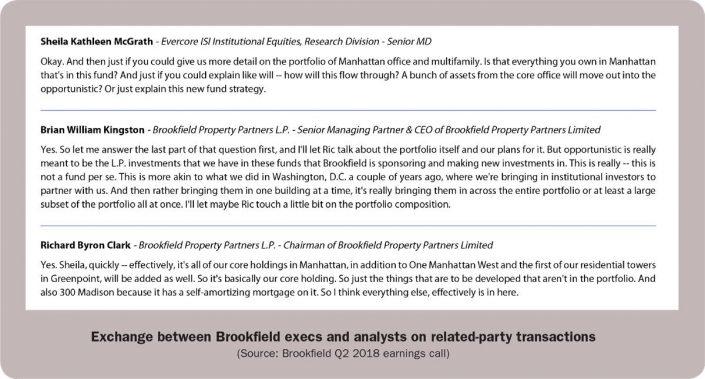

The Brookfield name is ubiquitous in U.S. real estate, but it can be difficult to discern which arm of the organization owns which property. That’s because Brookfield Property Partners often makes deals with other Brookfield entities.

These transactions — known as related-party deals — are sparsely disclosed in quarterly filings with securities regulators.

Take, for instance, Brookfield Property Partners’ 2018 sale of a 27.5 percent stake in a New York office portfolio for $1.4 billion to BAM.

“The only reason we did that,” Flatt told the Financial Times, speaking of the sale in a profile of the company in 2019, was that “it [BPY] needed some extra capital. And this was an easy way to do it.”

While Brookfield Property Partners disclosed the sale in its quarterly filings, it did not disclose a comprehensive list of the properties included at the time.

In response, a Brookfield spokesperson said, “the specific assets within that portfolio are well known to our investors and industry participants and easily accessible on our website and in other public-facing materials.”

In August 2019, Brookfield Property Partners sold an 81 percent stake in its 700,000-square-foot SoNo Collection mall in Norwalk, Connecticut, in a deal it said was worth $419 million.

“This is a fully stabilized mall in one of the highest-income demographics in the United States. We made a lot of development profit on this one,” Kingston said during the company’s third-quarter earnings call.

The deal was, in fact, between two related parties: Brookfield Property Partners and a BAM-controlled investment fund.

Kingston briefly mentioned this on the call, and Brookfield Property Partners did disclose a related-party transaction for a retail asset, but did not specifically identify the asset in its third-quarter report. The deal was disclosed as a related-party transaction and the asset was named, however, in Brookfield Property REIT’s annual filing.

“We have a robust process in place for managing all related-party transactions to ensure that any potential conflicts of interest are handled appropriately,” a Brookfield spokesperson said.

Such moves have attracted government attention in the past. In the summer of 2017, the SEC asked Brookfield Property Partners for clarification on a series of transactions the firm had first disclosed in its 2015 annual report.

Sixteen Brookfield senior officers invested $2 million in an entity called 9165789 Canada Inc., which held an indirect minority interest in a Downtown Los Angeles office portfolio, the company’s disclosures show. The transaction appeared to give Brookfield senior officers total control over the entity.

“The arrangement,” Brookfield said in the report, was to “align executives’ interests with those of the partnership.”

Brookfield did not disclose who these officers were or how much money they would make from the deal.

Bills, bills, bills

Asset valuation disclosures are important because they help illustrate a company’s financial health.

And understanding Brookfield Property Partners’ current health is important for its investors, because the firm has a hefty debt burden, with $9 billion of its nearly $48.9 billion in debt obligations coming due this year and in 2021, its second-quarter supplemental filing shows. (The second-quarter filings show $13.6 billion of secured debt coming due; the company said the discrepancy is because the supplemental filing only reflects the debt associated with the company’s specific interests in properties.)

The firm may be poised to take on more debt in the near future, as it and Simon Property Group are finalizing a $1.75 billion deal to buy J.C. Penney — a key anchor tenant at both operators’ malls — out of bankruptcy.

In May, BAM announced a “retail revitalization program,” which would recapitalize struggling retailers in markets where Brookfield is active. The company said it was targeting seed funds of $5 billion for the initiative.

In July, Moody’s downgraded its rating of Brookfield Property REIT (not to be confused with Brookfield Property Partners), which owns 122 retail properties across the U.S. The agency cited the REIT’s “elevated leverage entering the pandemic and the high likelihood of weakening operating income” as reasons for the downgrade, but said the high quality of its assets and the backing of its parent companies were credit positives.

As it stands, Brookfield Property Partners is far more leveraged than other major U.S. mall owners. Its debt-to-EBITDA ratio — a common measure of leverage — was 16 in the second quarter, according to Yahoo Finance. That’s compared to 7.1 for Simon Property Group and 12.2 for Taubman Centers in the same period.

Brookfield Property Partners’ access to BAM, of course, gives it firepower those rivals cannot count on. For that privilege, Brookfield Property Partners pays BAM a minimum annual fee of $50 million, plus an “equity enhancement fee,” according to its annual report.

At the September investor day, many of these issues surrounding its leverage didn’t come up. Instead, executives pitched their stock as a value opportunity. Like real estate, they argued, buying at the bottom of a cycle allows more upside than buying at the top.

“Today, our shares trade at a significant discount to the underlying value of our real estate,” Kingston said.

The value of that underlying real estate? That’s up to Brookfield.