Listening to Ben Ashkenazy’s lawyer, you might think the real estate mogul was living out the plot of “Air Force One.”

“The lender has come in like a hijacker and thrown them out of the pilot seat and said, ‘We now drive this 747. … Get out,’” attorney David Ross said at a May court hearing.

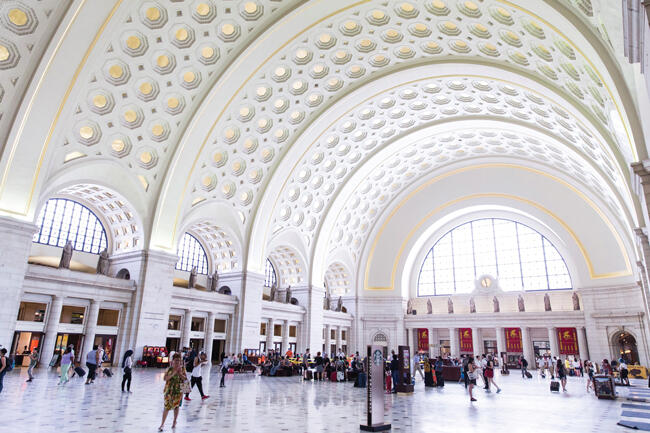

Ross took to the skies in his argument, but the property in question was in fact one of the country’s iconic train stations: the Union Station complex in Washington, D.C., a crown jewel in Ashkenazy’s $12 billion real estate portfolio before Amtrak seized the property through eminent domain in April.

Ashkenazy, his lender Rexmark and Amtrak are now tangled up over exactly how much Amtrak should pony up as compensation. Ashkenazy surely has the station’s $1.2 billion valuation from 2017 on his mind, but there’s a problem: Rexmark argues that it should be the one to negotiate the price. The lender is only motivated to recoup enough to cover its $430 million mortgage, which would leave nothing left over for Ashkenazy, who for 15 years poured his sweat and considerable equity into the complicated 425,000-square-foot rail, retail and office property.

“We’re throwing you out — with a parachute or not,” Ross said of the situation.

Rexmark’s lawyer took issue with that characterization.

“Them’s fighting words, as they say,” attorney David Scharf countered.

There are plenty of fights to talk about when it comes to Ashkenazy, whose résumé as a go-getting billionaire is underscored by a reputation for playing rough to get what he wants.

His list of combatants reads like a commercial real estate who’s who: He took on the mighty SL Green Realty with a move to hike the ground rent under a Midtown office tower the REIT controls, was accused of driving beloved department store Barneys into ruin and is mired in an ugly, drawn-out legal fight with his partners the Gindis (the family behind Century 21), whom he allegedly threatened to “go nuclear” on.

He’s also been blamed for allowing two marquee assets, the Harborplace property on Baltimore’s waterfront and Faneuil Hall complex in Boston, to fall into disrepair.

It’s a strange position for Ashkenazy to be in. Despite amassing an enviable portfolio spanning more than 15 million square feet, he has managed to stay so far below the radar that the press has described the 52-year-old as a “shy billionaire.” He dropped off the Forbes 400 last year, with the publication estimating that his current net worth is $2.6 billion, down from a high of $4 billion.

But the drama hasn’t stopped the deals, such as the former JCPenney store in Queens he bought for $40 million in December, or the redevelopment of the former Barneys space into a luxury residential building. He’s also gunning to take a multibillion-dollar REIT private, according to people familiar with his plans.

Ashkenazy declined to speak on the record for this article. But Joe Press, his chief operating officer at Ashkenazy Acquisition, told The Real Deal that the various conflicts come with the territory when running a property empire.

“The lion’s share of these are Covid-related,” Press said. “Less than 1 percent of the equity in our $12 billion portfolio was affected.”

Quick take

“I’ve got two lawyers claiming to represent the same client. I can’t live in that world,” D.C. federal judge Amit Mehta groused at the May hearing, as attorneys for Ashkenazy and Rexmark made their cases as to why they should be the ones to negotiate with Amtrak.

In 2007, Ashkenazy had paid $160 million for a long-term lease on Union Station, which is one of the nation’s top transit hubs and has 40 million annual visitors. He poured money into renovations, and a decade later the property was appraised at $1.24 billion. But the landlord soon found himself on a collision course with his rail-operator tenant.

Amtrak began making plans five years ago to overhaul the station, including repairing a tunnel under it, modernizing the concourse and expanding the passenger waiting area. It claims that it tried to coordinate with Ashkenazy but received “repeated rejections.”

Then, last fall, President Joe Biden passed his $1 trillion infrastructure plan. Amtrak saw an opening and in April filed a “quick take” eminent domain action. Ashkenazy claimed that he was blindsided by the move and that Amtrak took advantage of the pandemic to make a lowball offer: $250 million.

But that’s only part of it. In 2018, after Amtrak relocated the offices it had held at the station for 30 years, Ashkenazy levered up. When Covid hit, he, like many other retail owners, struggled, and a new appraisal wrote down the property’s value to $830 million in 2020.

Ashkenazy defaulted on his loan. And although Rexmark withdrew a scheduled foreclosure auction, the lender claims his default allows it to boot him from the ownership entity.

Representatives for Rexmark and Amtrak declined to comment.

Most eminent domain cases are open-and-shut: It’s difficult to argue the government doesn’t have the right to take a particular property. The most owners can usually do is hope for a price that makes them whole.

But Ashkenazy’s COO said they aren’t giving up.

“We happen to believe that this is one of the few instances where you can overcome an eminent domain quick take,” Press said.

Ground and pound

As if the government weren’t enough of an adversary, Ashkenazy is also mixing it up with New York’s largest office landlord in a contest that illustrates just how rough high-stakes real estate can get.

Ashkenazy became a potential headache for Marc Holliday’s SL Green in 2013, when he paid $400 million to buy the ground under the REIT’s 17-story office building at 625 Madison Avenue. SL Green was paying just $4.6 million in annual rent at the time, and the steep price Ashkenazy paid indicated he planned on a big increase when the mandatory rent reset came in 2022.

Ashkenazy’s vice chair, Michael Alpert, said in 2017 that the annual rent could go as high as $80 million.

Of course, SL Green wasn’t just going to sit back and let someone run its investment into the ground.

It knew that Ashkenazy and his lender on the deal, Children’s Investment Fund, were arguing over how much of the principal on the loan he was required to pay down.

SL Green saw an opportunity and bought the loan from Children’s. It then started turning the heat up on Ashkenazy to make additional payments, or be considered in default.

Meanwhile, the REIT held another mortgage a few blocks north on the Hermès-leased 690 Madison Avenue, which Ashkenazy bought for $115 million in 2015.

Ashkenazy defaulted on the loan during the pandemic, and the two sides negotiated for several weeks on an extension. A person close to Ashkenazy said that on the day they were set to sign the deal, SL Green reneged and foreclosed on the property — a move Ashkenazy saw as retaliation for 625 Madison. A source close to SL Green, however, said Ashkenazy wouldn’t meet the terms of the proposed extension, so the lender moved forward with the foreclosure.

A representative for the REIT declined to comment on the dispute. A spokesperson for Ashkenazy Acquisition said the company is going forward with the contractually obligated rent reset process, but declined to comment further.

Ashkenazy is looking to redevelop the former Barneys flagship store on 660 Madison Avenue

SL Green has reason to be concerned. Ashkenazy infamously jacked up the rent on Barneys’ space at 660 Madison Avenue to $30 million in 2018, from $16 million.

Barneys’ CEO at the time, Daniella Vitale, cited “excessively high” rents when the company went bankrupt the next year, and Ashkenazy came off looking like a heartless landlord who killed a New York icon.

A source at Ashkenazy Acquisition says it’s a depiction that rankles their boss, who believes an overaggressive national expansion is what put the department store out of business. As a stand-alone store, the flagship New York location was profitable even after the rent increase, the source said.

“It was everything else the company did that caused the bankruptcy,” they added.

Ramblin’ man

Ashkenazy lore has it that he was a real estate prodigy who did his first deal — a $2 million shopping center in the Bronx — at 17. But his story actually goes back even further.

His elementary school yearbook from the Solomon Schechter Day School on Long Island shows a mop-haired 12-year-old and lists a few interests (girls, waterskiing, MTV) along with his goals: to be a businessman and own a real estate company.

Born in Israel, Ashkenazy immigrated to the U.S. at the age of nine, when his father, Izzy Ashkenazy, moved the family to Nassau County in the late 1970s. Izzy founded a chain of retail stores called Concorde Jeans and became a figure in New York’s Syrian Jewish community of shopkeepers and landlords.

Izzy bought merchandise from some of the leaders in the community, such as Stanley Chera and Joseph “JoJo” Chehebar, and the Ashkenazys became part of the inner circle. In one early venture, Ben trekked to the Roosevelt Raceway Flea Market and camped overnight in his car so he could get a prime booth. He made a killing selling shorts.

Travel also played a formative role. During those first few years in America, the Ashkenazys crisscrossed the country in the family’s conversion van, staying in modest hotels along with throngs of middle-class tourists.

On one class trip to Washington, D.C., Ashkenazy saw Union Station for the first time. On a family trip to Boston, he took a tour on the Freedom Trail that stops at 16 historic locations. One of those stops is Faneuil Hall, the bustling marketplace that Ashkenazy bought decades later for $140 million.

Travel “gave him a unique perspective on a very wide array of assets that people don’t necessarily focus on if they’re not in that state or in that city or in that market,” said a person who’s known Ashkenazy since childhood. “Half the battle is just being exposed and knowing about these great assets.”

Spring chicken

One of Ashkenazy’s early jobs was location scouting for a chain of Roy Rogers franchises his father owned.

Back then, people sourced deals by placing classified ads in the real estate section of the New York Times. Ashkenazy took out an ad soliciting spaces for a AAA retail tenant, but what he was really looking for was properties to buy.

While checking out a restaurant space at that first Bronx shopping center, he discovered tenants were paying around $40 per foot, well below market. He bought the property and leased the space to his father’s Roy Rogers at the going rate: $140 a foot. There would be no family discounts in a deal-junkie household.

Around this time, in the late 1980s, Izzy suggested his son move to Texas. It was during the savings and loan crisis, and investors could snap up properties from the Resolution Trust Company and the FDIC for pennies on the dollar, with the federal government kicking in up to 90 percent of the financing.

Ashkenazy took his dad’s advice and moved to Houston in 1988. He cut an impressive figure: By the simple fact that he came from New York, people assumed he was a big deal. And he played that up, whipping around town in a Porsche 911, wearing expensive suits, holding court at the city’s best restaurants. He even stayed in the most expensive room in the most expensive hotel: the presidential suite at the JW Marriott. The hotel was owned by a pair of friends from New York — Morris Bailey and Stanley Chera — who upgraded him for three months.

Texas allowed Ashkenazy to do deals at scale, and he amassed a 2 million-square-foot portfolio of office buildings and retail centers.

“For someone who wakes up at 4 in the morning and goes to bed at 12, it was like a playground,” said the person who’s known Ashkenazy since his early years.

The Lone Star State is also where Ashkenazy honed the style of dealmaking he’s known for today. He targeted undervalued properties and realized his aggression could give him an edge. He did deals by handshake, moved quickly to put down large deposits and often preempted deals by making an offer while others were preparing their bids.

He sourced off-market deals and started flipping contracts as a way to amass equity he could invest in bigger properties. He also got a taste for trophy assets, which he believed would always increase in value.

Ashkenazy is mired in a compensation battle over the Union Station in Washington, D.C.

One day, Ashkenazy and his fiancée, Debra, visited San Antonio. The city’s attractions include the Alamo, Sea World, Six Flags and the River Walk — a winding canal that’s the Southwest’s best imitation of Venice.

The canal terminates inside Rivercenter, a 1 million-square-foot mall and tourist magnet.

Ashkenazy snapped a photo of Debra with the mall in the background. When he came back to buy the mall in 2005, he showed the photo to the sellers.

We’re a happy family

Flush with capital, Ashkenazy moved back to New York in the early 1990s and went on a buying spree. In 2001, while still in his early 30s, he teed up his biggest deal: the Barneys space at 660 Madison.

The tony department store was paying $16 million annually for its lease, with the rent scheduled to reset in 18 years. Its prime location at 61st Street, a block from Central Park, also meant it had development value.

But the deal had some hair on it. Barneys had already been through a bankruptcy in 1996 after Barney Pressman’s family teamed up with a Japanese investor, the Isetan department store company, to finance an expansion. By 2001, there were doubts about the company’s long-term sustainability.

Ashkenazy had set up a meeting with Scott Latham, the broker marketing the Barneys properties in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, to talk about another deal. When the subject of Barneys came up, Ashkenazy told Latham he was ready to go hard with a nonrefundable $10 million deposit — no contingencies.

It worked. He bought the three Barneys properties for $190 million.

Another trophy was the Plaza Hotel. He made an unsolicited offer in 2017 to buy into the stake owned by Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal — at the time the world’s seventh-richest person. He arranged to meet with the prince on the ski slopes in Courchevel, France, and the two hammered out a deal: Within the span of two weeks, Ashkenazy had a piece of the Plaza and teamed up with Alwaleed to buy the Grosvenor House hotel in London.

“He did those deals direct, and he moved very quickly to get them done,” said Jeff Davis, a hotel specialist at JLL who worked with Ashkenazy on the transactions.

“That’s his competitive advantage in the marketplace,” Davis added. “Sometimes you have buyers who are a little more flaky, less brash. When he knows what he wants, he knows how to get it.”

God’s plan

When Ashkenazy threw a Bat Mitzvah party for his daughter Gigi in 2016, he hired Drake to ring in the festivities at the Rainbow Room. For his son Isaac’s Bar Mitzvah, Justin Bieber performed.

Though press-shy, Ashkenazy isn’t one for a modest lifestyle. He’s known to enjoy games of high-stakes backgammon on his boat, Lionheart. Named in honor of his wife, the vessel is his third. The first one sank as the ship’s captain was sailing it to meet the family so they could board it for the first time, according to insurance documents.

When in New York City, Ashkenazy lives at the Stanhope, the Rosario Candela-designed former hotel at 995 Fifth Avenue across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The building’s residents have included brewing heiress Daphne Guinness and hedge funder Paul Solit. And he’s got one of the ultimate billionaire status symbols: a professional sports team.

In 2013, he bought a stake in Israel’s Maccabi Tel Aviv basketball club, which has a passionate fan base. At the time, Ashkenazy explained that one of his idols growing up in Israel was Maccabi player Aulcie Perry, who’s been described both as the Michael Jordan and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar of Israel. Born in Newark, N.J., Perry was cut from the Knicks before guiding Maccabi to two EuroLeague and nine Israeli League championships in the 1970s and 1980s.

“To me, Maccabi is one of the strongest Jewish symbols in the world,” Ashkenazy said at the time. “I am proud to give something back to the team and to the country that I love so much,” he added, describing the purchase as “the realization of a dream.”

Ashkenazy attributed a lot of his success to his father, who died this February. During his eulogy at the funeral service in Israel, he recalled an episode from his Texas days, when he was thinking about buying a property and asked Izzy if he wanted to come from New York to see it.

“Do you love the building?” Ashkenazy recalled Izzy responding. “If you do, then I don’t need to see it.” That confidence, he said, was the greatest thing a father could give a son.

“Chillul hashem”

In New York’s tight-knit Syrian Jewish community, families are constantly doing business with one another. And when disputes arise, they usually look to resolve them internally.

So it was a shock when Ashkenazy went rogue during his fight with the Gindis.

From 2005 to 2015, the partners had invested in seven properties together in New York, L.A., Chicago and Montreal. But in late 2020, Ashkenazy sued the Gindis — Raymond and his cousins, Eddie and Isaac — claiming they failed to meet capital calls and were trying to strong-arm a premium buyout.

What’s more, Ashkenazy said, the Gindis had gone around telling prominent community members that he had stolen from them. He named members of the Dweck, Adjmi, Chehebar and Cayre families — basically a social register of the Syrian Jewish community — involving them in the very public fight.

One prominent community member called the situation a “chillul hashem” — a Jewish term for desecrating God’s name by making Jews look bad.

“It’s ugly, and it shouldn’t have gotten to where it got to,” the person said. “It should’ve been mediated by the community.”

Maybe even more shocking is what happened when the Gindis filed a counterclaim, accusing Ashkenazy of intimidation tactics and alleging $21 million in damages. The Gindis — whose Century 21 went bankrupt during the pandemic — said Ashkenazy once texted Raymond and became enraged, threatening to “go nuclear if I need to because you destroyed my business.”

It was typical Ashkenazy behavior, they said: One minute he’d be talking amicably about resolving their dispute, and the next he’d be throwing a tantrum.

A spokesperson for Ashkenazy declined to comment on the lawsuit, and members of the Gindi family did not respond to requests for comment. The case has now dragged on for 19 months, while the properties languish.

Yair Talmor, chair of the credit committee at Bank Hapoalim, counts both sides as clients. He said many people in the community have tried to help smooth things over.

“We tried to do our best to bring them together on one or two occasions and resolve the issue,” he said, acknowledging how tough the situation is. “I read what’s in the papers.”

At the ICSC trade show in December, Ashkenazy rented an office space on the top floor of the Las Vegas Convention Center, perched over the hoi polloi scurrying around the convention floor. If the struggling retail market or the battles he’s fighting were a concern, he wasn’t going to let it show.

In New York this May, an appeals court ruled in his favor regarding the timing to repay his loan in the dispute with SL Green on his mortgage at 625 Madison. He’s also working on his plan to redevelop the former Barneys space at 660 Madison. A source close to him said he’s working through talks with the Safra family, which owns the office space above his retail condo, on an agreement to redevelop the site.

And he’s getting into the REIT space. During the 2020 lockdown, which put a freeze on investment sales, Ashkenazy purchased a 10 percent stake in the mall landlord Macerich. (The move required Macerich’s board to change its bylaws to allow a single investor to buy more than 5 percent.)

Sources said Ashkenazy has been working for the past year and a half on a deal to take a $4 billion REIT private — a purchase that would significantly upsize his portfolio.

The foreclosures and legal battles he’s dealt with represent only a sliver of his $12 billion portfolio, which the company says is safely levered with $5 billion in debt. But the attention from them has been unwanted.

Charlie Kushner, who partnered with Ashkenazy in 2005 to buy the Monmouth Mall in New Jersey, said the mogul has two sides that can’t be separated: a skilled investor and a hard-charging negotiator.

Real estate is, after all, defined by relationships — buyer and seller, landlord and tenant, borrower and lender — that start out friendly but have the potential to turn hostile. The industry’s titans aren’t exactly known for tiptoeing their way to the top.

“Ben is one of the shrewdest people in our industry. He’s brilliant and creative,” Kushner said. “He’s definitely an aggressive guy, which is why he’s so successful. He knows how to make deals and knows how to defend himself and beat out other people.”

Some might say them’s fighting words.