After a decade of historically low interest rates, during which funding for new developments and real estate purchases flowed with relative ease, the party finally came to an end this spring, when the Federal Reserve began raising rates to slow inflation.

With the cost of debt climbing and lending expected to decline in the second half of the year, a slowdown in dealmaking and development could be on the horizon.

A jump in interest rates “freezes things for a period of time until people sort of make decisions for themselves,” said Russell Schildkraut of the debt and equity brokerage Ackman-Ziff Real Estate Group. “So you sit there and you’re like, ‘Well, I don’t have to finance now, so I’m not going to.’ But at some point, people want to do things and it’ll have to work itself out.”

Rising rates have already cratered demand for home loans — applications for which dropped to their lowest level nationally in more than two decades last month — leading to scores of layoffs this summer at major mortgage lenders including JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo, which now intends to pull back on its mortgage business, Bloomberg reported last month.

Those conditions could present a challenge for New York City’s pandemic recovery, which has been driven in part by cheap debt that enabled the city’s top lenders to combine for more than $30 billion in commercial and residential mortgages over the past year.

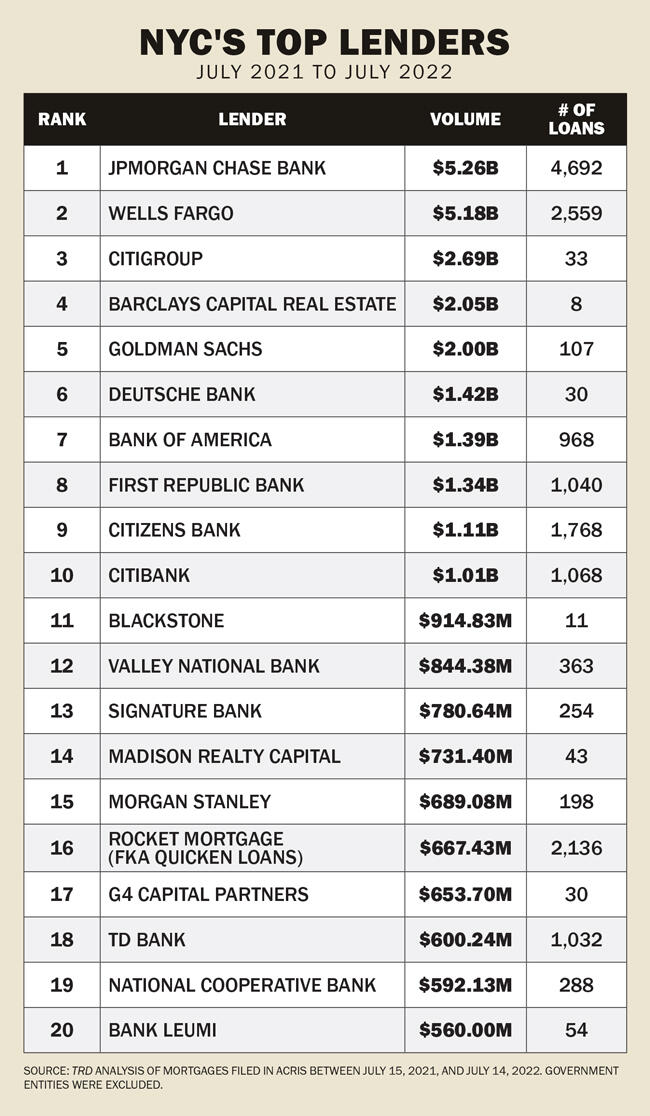

To assess the industry’s biggest financial backers in the waning months of the low-rate era, The Real Deal examined mortgages recorded in the city register between July 15, 2021 and July 14, 2022.

Despite concerns over the ongoing impact of remote work on Manhattan’s unsteady office market, the city’s top lenders handed out some of their biggest financing deals to office landlords.

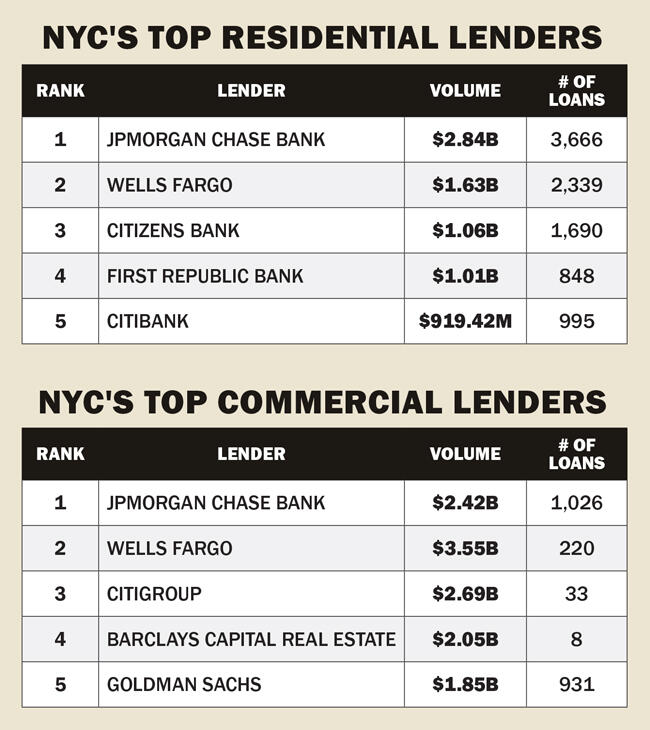

Behind a nine-figure loan to refinance a Midtown Manhattan office building, JPMorgan led the way in terms of both commercial and residential mortgages. In total, the investment bank doled out $5.26 billion across almost 4,700 loans between July 2021 and July 2022, including $2.8 billion in residential mortgages.

Behind a nine-figure loan to refinance a Midtown Manhattan office building, JPMorgan led the way in terms of both commercial and residential mortgages. In total, the investment bank doled out $5.26 billion across almost 4,700 loans between July 2021 and July 2022, including $2.8 billion in residential mortgages.

The bank’s largest individual loan in the 12-month reporting period came in June, when it provided Rudin Management with $194.4 million to refinance its office tower at 3 Times Square.

It also provided developers Steve Witkoff and Len Blavatnik with two mortgages adding up to $315 million to complete the stalled XI luxury condo development on 11th Avenue in Chelsea, which Witkoff and Blavatnik took over from embattled developer HFZ Capital Group late last year.

Wells Fargo nabbed second place, handing out $5.1 billion in mortgages across more than 2,500 loans, including $1.6 billion for homes.

Alongside Deutsche Bank, Morgan Stanley and Citigroup, the bank led a $1 billion refinancing of Boston Properties’ 59-story, 1.7-million-square foot office tower at 601 Lexington Avenue in Midtown. The 10-year, fixed-rate mortgage package included $384 million in new debt.

But the largest mortgage provided in the 12-month period came from Citigroup and Barclays, third and fourth, respectively, in this year’s ranking. In January, the banks lent $1.7 billion to Missouri-based Storagemart for its $3 billion acquisition of Manhattan Mini Storage from Edison Properties.

Citigroup issued $2.69 billion across 33 loans, while Barclays doled out $2.05 billion over just eight loans. Goldman Sachs rounded out the top five, handing out $2 billion across 107 loans in the 12-month period.

Despite the big-ticket loans, financing for office buildings has grown more challenging as demand for space remains uncertain, Ackman-Ziff’s Schildkraut said.

“If you’re a capital provider, I think they’re trying to get their arms around it and I don’t know how long it’s gonna take to understand the demand side of the equation,” he said. “As a result, office has become very tricky.”

Chris Coiley, who heads Northeast commercial real estate lending at Valley National Bank (12th on the ranking), was blunt in his assessment of the office market.

“Office is definitely not the darling of the ball right now with a work-from-home model that maybe is here to stay,” Coiley said.

Still, Coiley said he’s confident things will bounce back.

“I do think you’re gonna start to see, in the major cities, people starting to get back to work, and that need for collaboration is something that is evident,” he said. “We’re starting to see more activity and we’re hearing the right things from some companies along those lines.”

Valley National provided $844.4 million over more than 360 loans in the 12-month period. Its largest was to Cheskel Swimmer’s Chess Builders for a 66-unit rental building at 3240 Riverdale Avenue in Kingsbridge, the Bronx, in line with the bank’s strategy of focusing on multifamily assets, Coiley said.

“When it comes to the multifamily side, first and foremost, people need a place to live,” Coiley said. “They need a roof over their head and that’s always gonna be probably the safest kind of investment when it comes to real estate owners and what they get into.”

Coiley described Valley National’s commercial lending strategy as “sponsor-driven” — familiar borrowers on which the firm can feel comfortable placing its bets.

“Making sure that the execution risk isn’t there and you have somebody on the development side that can complete a project without any problems,” Coiley said. “You’re really looking at the combination of who you’re lending to and what type of project.”

With rates rising, borrowers have more to take into account before moving ahead with a project or investment.

“There’s an additional component that you have to bring into play,” Coiley said. “Am I buying that piece of land at the right price? Can I put up a building at the right numbers for it to make sense so I can get my return? It’s a mathematical equation, but it’s like hitting a moving target right now.”

Coiley expects that as lending slows in the coming months, investment and financing deals will center around dependable assets.

“What we’re seeing is everybody cautiously optimistic, and that’s from our larger customers to our smaller customers,” he said. “You’re seeing the investment strategy is still there. Maybe not so much in the riskier asset classes, but maybe they’re focused on more multifamily and more industrial.”

While those classes may be seen as safer investments than other commercial assets, limited supply and increased demand from institutional investors could further drive up prices. After the property tax break 421a expired in June, multifamily construction in the city is expected to come to a standstill. And even the booming market for last-mile warehouses will be tested if the shrinking economy diminishes consumers’ online spending.

Still, Ackman-Ziff’s Schildkraut echoed Coiley’s tempered but hopeful assessment.

“I can see a scenario where people say, ‘Well, maybe it’s not so bad,’” he said. “Who knows what’s gonna continue, but I can see a scenario where people say, ‘Alright, I have this capital and I wanna put it out.’”

“They’ll be cautious so it’ll take time,” he added. “But I can see a scenario where it actually gets better sooner rather than later.”