In January, French investment bank Natixis agreed to provide a $95 million loan for 500 North Michigan Avenue, a 24-story office building on Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. The deal would be a relatively small notch in the belt for a commercial lender with increasing clout in major U.S. markets.

But weeks later, the bank walked back its offer — a puzzling move in an industry where being able to deliver loans is crucial to reputation.

Then in June, Natixis pulled out of a deal at the Coca-Cola Building at 711 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, where it had signed a term sheet to fund 90 percent of a $900 million acquisition by Nightingale Properties. The following month, the bank withdrew from a commitment with Apollo Global Management to provide a $900 million loan to refinance the commercial portion of the iconic Crown Building, also on Fifth Avenue.

“It’s rare that you see that [happen] when there’s a lot of liquidity and not a credit crisis,” said Aaron Appel, a debt broker who represented the landlord at the Crown Building.

The saga is just one symptom of the current lending climate in New York. Ever-growing competition and recent interest rate cuts have pushed loan prices down, and while most large banks have remained prudent, leverage has started to creep up.

This backdrop has emerged as other signs of disruption have rattled lenders. New York’s new rent laws have impacted community banks that rely heavily on financing rent-stabilized buildings, and residential condominium sales are crawling, forcing some developers and landlords to default on massive loans.

The rise of flexible office space has also bent the rules on lending. Some big banks have started to issue loans on buildings that contain a high concentration of co-working tenants — arrangements typically reserved for tenants with higher credit ratings, such as law firms. In some deals, lenders like Citigroup are financing buildings that are largely occupied by WeWork, which is gearing up for a controversial IPO this fall. Such loans were virtually unheard of just a few years ago.

These factors are front and center for commercial lenders and borrowers in New York as the economy powers into its 10th straight year of growth, one of the longest bull markets on record. With signs that development is slowing, institutional lenders are still scrambling for deals, The Real Deal’s ranking of the city’s top commercial real estate lenders shows.

These factors are front and center for commercial lenders and borrowers in New York as the economy powers into its 10th straight year of growth, one of the longest bull markets on record. With signs that development is slowing, institutional lenders are still scrambling for deals, The Real Deal’s ranking of the city’s top commercial real estate lenders shows.

“What we have noted is that folks are getting out of their traditional swim lane,” said Mark Myers, head of commercial real estate at Wells Fargo, which topped this year’s nonconstruction ranking. For example, “life insurance companies, who have historically been a fixed-rate lender, have now raised money to compete in the short-term value-add space,” he noted.

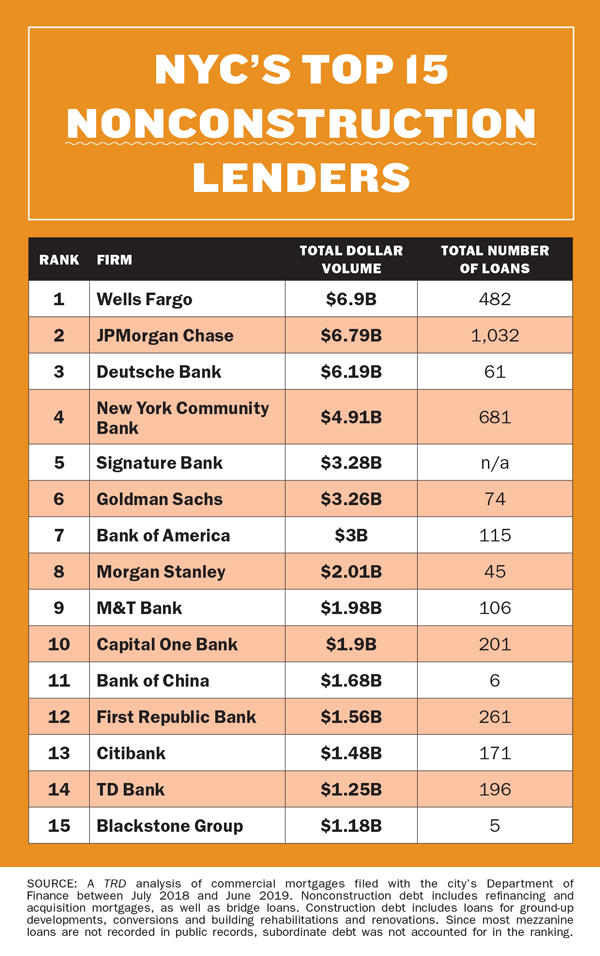

Natixis — which took 11th place in last year’s tally of the city’s top nonconstruction lenders but did not make this year’s ranking — is just one of several firms to be impacted by the current lending climate.

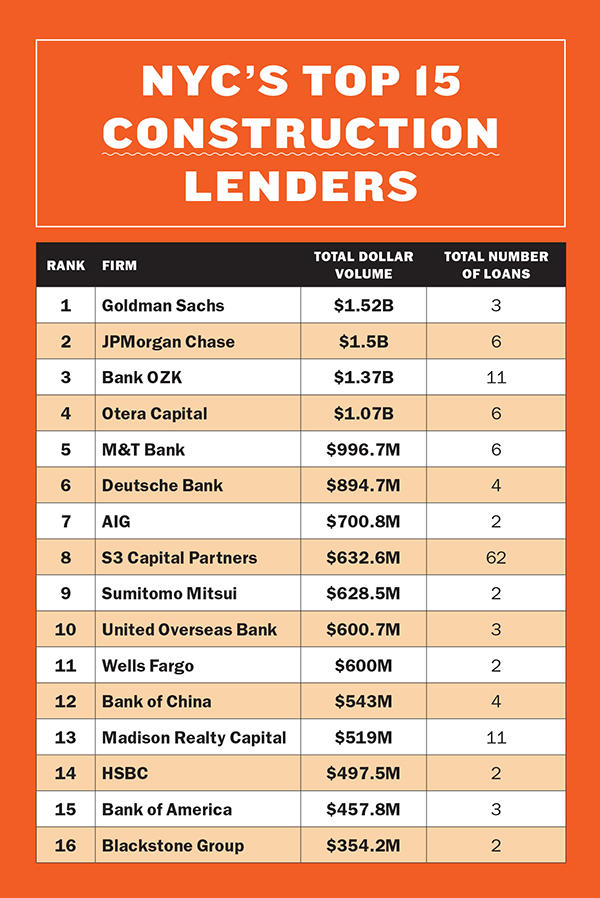

Several construction lenders also slid down the ranking, including Madison Realty Capital (from fourth to 12th), HSBC Bank (from sixth to 13th) and Children’s Investment Fund (from fifth to not making this year’s tally).

“In certain deals there is a race to the bottom,” Appel, who recently left JLL to start his own finance brokerage, said of New York’s commercial debt market.

Major players trade spots

In TRD’s latest ranking, which tracked loans issued throughout the five boroughs between July 2018 and June 2019, traditional lenders dominated both construction and nonconstruction debt deals.

Nonbank lenders — including life insurance and private equity firms, debt funds and CMBS shops — did not rank highly, in part because many of them specialize in mezzanine deals, which were not tracked by TRD.

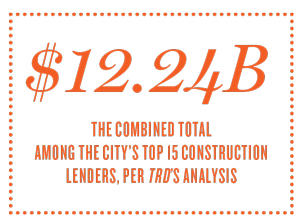

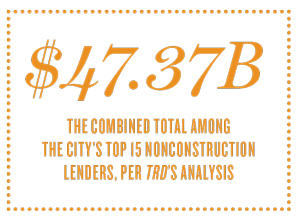

But the ranking revealed that construction lending fell far short of nonconstruction lending, a factor exacerbated by the market nearing the end of a prosperous cycle. The top 15 nonconstruction lenders collectively issued $47.37 billion in loans, compared to just $12.24 billion issued by the top 15 construction lenders.

“On the construction side, there’s certainly fewer projects because the condo market in New York is challenged right now,” said Dustin Stolly, co-head of Newmark Knight Frank’s debt and structured finance division. “There’s not the same pipeline that there was two or three years ago in the cycle.”

Among the top construction lenders in the city, Goldman Sachs led the pack with $1.52 billion divided among three large deals, including a $1.13 billion loan to the developers of TSX Broadway, a 46-story tower rising above Times Square. The investment banking giant was closely followed by JPMorgan Chase with $1.5 billion across six deals, Bank OZK with $1.37 billion across 11 deals and Canada’s Otera Capital with $1.07 billion across six deals. M&T Bank rounds out the top five construction lenders with $996.7 million divided among six deals.

For nonconstruction lending, Wells Fargo took the top spot on that list with $6.9 billion divided among 482 deals. The San Francisco-based bank was followed by JPMorgan Chase with $6.79 billion across 1,032 transactions, Deutsche Bank with $6.19 billion across 61 deals and New York Community Bank with $4.91 billion spread across 681 deals. Signature Bank completes the top five with $3.28 billion, though it did not provide the number of deals.

Nonconstruction lending over the past year has largely been driven by landlords looking to refinance projects with long term, cheaper fixed-rate debt, said Anthony Wong, Bank of China’s New York head of commercial real estate, who oversaw the issuance of $1.68 billion of nonconstruction debt in the ranking period.

In a statement, he said that nonbank lenders have crowded the field with competitive loans signed at higher leverage points, which are unavailable to traditional lenders.

Rent laws rattle industry

Rent laws rattle industry

A number of factors have walloped the commercial lending sector, but none more recently than the state’s new rent laws. This summer, decades of landlord-friendly laws were rolled back in favor of tenant protections, which are expected to drag down the value of some stabilized buildings in the boroughs.

The city’s biggest multifamily lenders, including NYCB, Signature and Dime Community Bank, have felt the immediate brunt of those changes. In the months after the debate around rent laws gained traction, those three banks collectively lost $2.5 billion in market capitalization.

In June, NYCB’s president and CEO, Joseph Ficalora, acknowledged that lenders who took a bet on the stabilized rents increasing will suffer a loss.

“Those that we compete with, who lend $20 million more than they should … relying on perceived future value, they will in fact default,” he said at Morgan Stanley’s U.S. Financials Conference in New York.

NYCB saw a 23 percent drop in its share price from its March peak following the flood of news about the rent law before Gov. Andrew Cuomo officially signed it. While its share price has bounced back, the bank has made cuts, and last month sold a branch building in Coral Gables, Florida, for $12 million.

Despite the turmoil, the Long Island-based bank conducted the second-highest number of transactions next to JPMorgan. NYCB closed a total of 1,036 deals across construction and nonconstruction loans in the time frame.

For one of its largest loans, the community bank partnered with Morgan Stanley to provide a $900 million loan for the Starrett-Lehigh Building at 601 West 26th Street, which is being redeveloped by RXR Realty to include a new entrance, retail space and food hall.

NYCB did not respond to requests for comment.

Oversupply, and less demand

Across the lending spectrum, a glut of debt in the market has also forced downward pressure on loan prices. Borrowers with more lending options are easily sold on lower price points and lower interest rates.

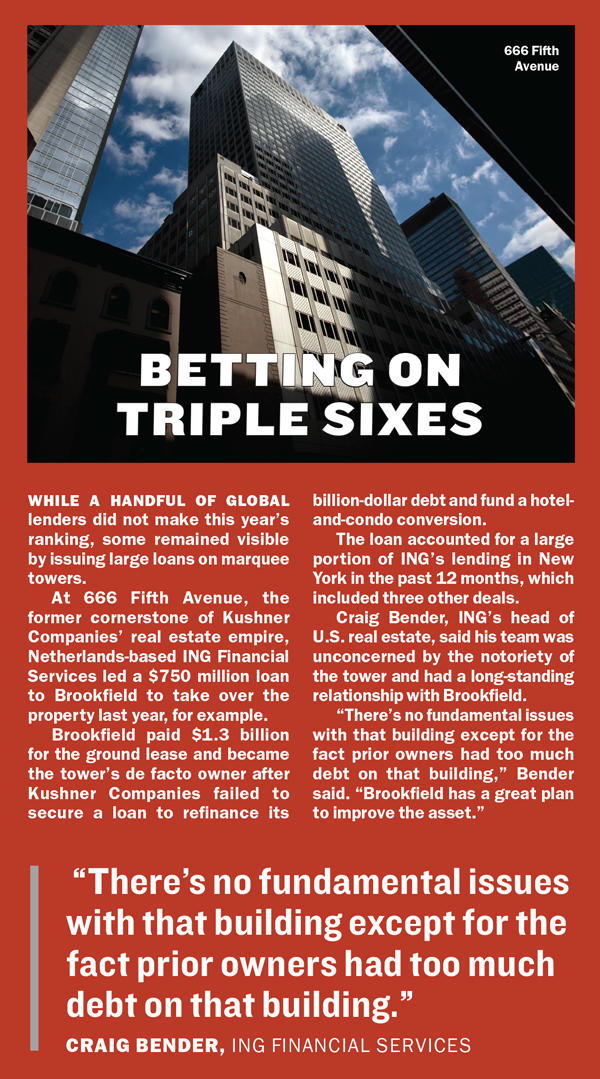

“We have seen interest margins decline 20 to 25 basis points over the last 90 to 120 days,” said Craig Bender, head of U.S. real estate at ING Financial Services.

In one price-war episode last November, Deutsche Bank outmaneuvered JPMorgan to provide a $750 million loan for One Wall Street, the 50-story tower being redeveloped by Harry Macklowe’s eponymous firm. JPMorgan had been in negotiations for more than a year to provide an $850 million loan, but sources told TRD at the time that Deutsche offered a lower interest rate, at around 5 percent.

Representatives for Deutsche and JPMorgan declined to comment.

Deutsche’s bid also trumped an effort by Singapore’s GIC sovereign wealth fund, which had offered a “high-leverage option,” according to Appel, who represented Macklowe in the deal.

The German financial giant’s real estate lending has remained steadfast as internal struggles have persisted over the past year. In July, Deutsche said it would cut 18,000 jobs and shutter its investment banking arm’s equity sales and trading divisions as it sought to cut costs. It has posted losses in four of the past five years, and record losses are expected for 2019.

But the bank has been sure to remind New York developers that its real estate lending division — considered a cash cow for the bank — is here to stay. In addition to One Wall Street, Deutsche also led a massive loan to Silverstein Properties, an $800 million transaction for the American Broadcasting Company’s headquarters.

Other lenders facing internal struggles have also maintained lending volumes. Bank OZK, the Little Rock, Arkansas-based community bank, has been dogged by executive departures and complaints of sexual misconduct, as TRD reported in last month’s cover story. Despite this, the lender’s loan volume remained among the largest in New York, and it ranked as the third-largest construction lender.

While low price points have given borrowers a leg up to secure cheap debt, those developing residential condominiums have run into a different issue: An oversupply of condos is dogging sales figures. Without sales capital, some developers have made missteps in attempting to complete their projects.

At 125 Greenwich Street — which got started in 2014, during the height of the market — the luxury tower remains incomplete. Crawling sales have forced the project’s sponsors into default, and two foreclosure proceedings are pending at the building. Construction crews were owed as much as $40 million at the site in May, and in July, United Overseas Bank sold its $195 million senior loan at the project to a BH3 Capital, a Florida firm with a reputation for taking over projects.

Farther north at 45 Park Place, a 43-story luxury residential tower, developer Soho Properties has been unable to refinance the project since the start of the year. Led by Sharif El-Gamal, the developer was in negotiations with Madison Realty Capital for a $170 million loan, but those talks fell apart, according to a person familiar with the matter. The developer also landed in hot water after contractors at the site went unpaid for almost a year and were owed $10 million.

Madison Realty Capital declined to comment. Soho Properties did not respond to requests for comment.

The co-working complex

Another factor that has forced change in lending conventions is co-working, the hottest trend in commercial real estate.

Some lenders have watched their exposure to the fast-growing industry, particularly WeWork, skyrocket. And though WeWork’s business model has yet to be tested in a U.S. economic downturn, many lenders are taking on more risk by issuing loans to buildings with a high occupancy rate of co-working tenants.

Last September, Citi Real Estate Finance issued $480 million in debt to Kushner Companies, RFR Holding and LIVWRK to refinance another loan provided by the bank for the five-building Dumbo Heights complex. One of those buildings, 81 Prospect Street, is wholly occupied by WeWork.

And in June, Bank of America provided a $74 million loan to landlord Walter & Samuels for 214 West 29th Street, a 125,000-square-foot building where WeWork occupies 80 percent of the space.

These occupancy rates are far north of what some traditional lenders are prepared to become involved in. Wells Fargo, which has provided loans to multiple buildings that are occupied by WeWork, will typically refuse to provide loans to buildings with more than 20 percent occupancy by flexible office space firms, according to Myers.

“Generally speaking, we have tried to limit our exposure to co-working and noncredit tenants,” said Myers, the bank’s head of commercial real estate. “But it’s going to be building-specific, market-specific and borrower-specific. There’s a lot to the equation.”

A cautionary tale

After Natixis withdrew from lending to two hallmark Manhattan towers, multiple industry players who spoke to TRD said the pullback either indicated that the bank was showing signs of internal trouble or that the volatile local market conditions were having an effect.

After all, they said, a lender’s ability to provide loans is key to attracting future deals.

“The ability to craft a deal that a lender and borrower can close on is so paramount of all the reputations involved,” said George Doerre, a vice president in M&T Bank’s commercial real estate division.

In a statement, Natixis said it is “actively lending nationwide” and has closed $3.7 billion of debt this year. It added that it has a pipeline of $5.3 billion split between portfolio deals and CMBS.

In the meantime, other lenders have filled the bank’s void. Apollo Global Management agreed to provide the entire $800 million loan at the Crown Building, and JPMorgan was recently revealed to be leading a $700 million loan at the Coca-Cola Building.

As the U.S. economy slows, banks have repeatedly said they are being timid in their lending. But it remains to be seen if Natixis’ move was a cautionary tale.

“Overall, I think lending has largely been disciplined to this point,” Doerre said. “Everyone is watching very prudently.”

Correction: The September issue story “Banking on volatility” inadvertently excluded S3 Capital Partners from the top construction lender ranking. The firm ranked No. 8 with $632.6 million in total debt deals in 2018.