For decades, New York City has offered communities an enticing deal: Approve new housing and locals will get half of the affordable units.

But in 2014, the Obama administration warned the city that so-called “community preference” might be reinforcing segregation.

The city balked, offering to tweak the policy but not to dump it. “Without any promise of local benefits,” wrote Vicki Been — then head of the New York City’s main housing agency — getting local buy-in for projects could be “extraordinarily difficult.”

Federal housing officials felt community preference conflicted with an Obama administration rule requiring municipalities to show how they are combating exclusionary housing. But last summer the Trump administration repealed the Obama measure, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, and the city’s policy remains unchanged.

Now, with President-elect Joe Biden planning to restore the fair housing rule and a federal lawsuit against community preference underway, the policy could come under scrutiny again. Mayoral candidates, too, have criticized the city’s practice and vowed to reform how it awards affordable apartments.

The fight is part of a national debate pitting the interests of local residents and the real estate industry against the need to unwind policies that cause or exacerbate segregation. Biden staffers have already laid out plans to expand and reform key affordable housing programs to better align with the Fair Housing Act.

But reversing the course set over the Trump years — let alone decades’ worth of government-sanctioned segregation — will be an uphill battle. And though Biden will control the Department of Housing and Urban Development and have a Democratically controlled Congress, it isn’t as if he can simply flip a switch on the nation’s housing problem.

“At this point, it is probably in worse shape than it has been in 20 years,” said Robert Silverman, an urban planning professor at the University at Buffalo. “HUD’s going to have a lot on its plate.”

Rethinking Section 8

Some federal programs have only just started to incentivize the construction of affordable housing in more affluent areas.

The efforts give low- and moderate-income residents more agency to move to “high opportunity” areas, so-called for their low crime and access to good schools, mass transit, government services and other amenities.

For roughly a decade, Dallas, for example, has approached housing vouchers for low-income tenants differently from most of the country.

But not voluntarily.

The local nonprofit Inclusive Communities Project had sued HUD more than a decade ago, arguing that the way it determined how much rent the federal government paid through Section 8 vouchers further insulated minorities in communities “marked by conditions of slum and blight.”

Because rent subsidies were the same in poor Dallas neighborhoods as rich ones, tenants tended to stay in low-income areas where the vouchers covered a higher percentage of their rent.

A 2011 settlement required the city to base the value of rent vouchers for low-income tenants on the going rents in individual ZIP codes, rather than citywide. In the final months of the Obama administration, HUD rolled out a version of that for the rest of the country, dubbed Small Area Fair Market Rents.

As with Obama’s fair housing rule, the Trump administration attempted to suspend the program, but a federal court upheld it in December 2017.

Traditionally under Section 8, low-income tenants with vouchers pay 30 percent of their income on rent, and the federal government pays the rest — to a point. Local housing agencies determine how much is covered based on the average market rent, which often encourages tenants to remain in low-income areas.

“It was creating a sort of disincentive to move to a higher-opportunity area,” said Silverman, who co-authored a report for the Poverty & Race Research Council on the Small Area program’s first year.

Under the program, as with Dallas’ settlement, housing agencies use ZIP codes, rather than larger areas, to calculate the percentage of average market rent covered by vouchers. Housing voucher recipients in Dallas have seen an improvement in neighborhood quality since 2011, according to Silverman’s report.

But in the first wave of the program, some cities set federal rent payments below the average market rate in both low- and high-income ZIP codes, limiting renters’ incentive to move up, Silverman noted.

His report calls on HUD to make wealthier neighborhoods more attractive to tenants by issuing new guidelines.

Some cities have since opted on their own to use small area rents.

Boston applied them in more than 230 ZIP codes in July 2019 to give families “the choice to rent in areas that have historically been unaffordable with a voucher,” the city’s housing authority said.

Segregation in Boston is stark and persistent. Two-thirds of its Black population live in three city neighborhoods, according to Boston Magazine. More than 40 percent of the 147 municipalities in the Greater Boston area are at least 90 percent white, the publication reported.

In recent years, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker has pushed for more housing by weakening local authority to block projects. One bill was backed by several developer and broker groups in the state, but was criticized by housing advocates and some legislators for prioritizing market-rate housing.

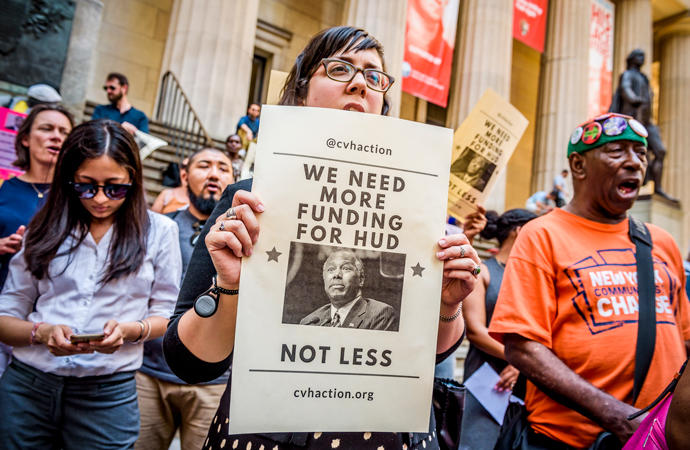

Protesters rallied against HUD in front of the New York Stock Exchange in June 2017 (Getty Images)

“Racist, exclusionary zoning is a real thing,” state Rep. Mike Connolly told Boston Public Radio last July. “Just because you make it easier to zone for new housing doesn’t ensure it’ll be affordable for the people who need it most.”

This month the legislature and governor reached an agreement as part of a $630 million stimulus bill. The compromise included some of the reforms promoted by advocates, including requirements for multifamily housing suitable for families with children in certain areas, but didn’t incorporate all of the affordability requirements sought by its critics.

Balancing acts

The real estate industry’s role in perpetuating exclusionary housing practices has been well documented. Newsday’s 2019 investigation laid bare how some Long Island brokers steered home shoppers to certain neighborhoods based on their race, for example.

When it comes to construction of affordable housing, developers have argued that local zoning, high land costs and other market conditions dictate what they can build. They have also pointed to fierce local opposition from well-organized NIMBYs.

The country’s Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program — a major funding source for affordable housing — has drawn similar criticism as Section 8 for incentivizing new development in low-income areas rather than higher-opportunity neighborhoods.

Biden has pledged to expand the subsidy program and ensure that “urban, suburban and rural areas all benefit from the credit.” And Congress recently made a critical change to make the tax credit more valuable and potentially allow affordable housing developers to put more equity into projects.

Aaron Koffman of Hudson Companies, which builds affordable and market-rate housing, said he’s hopeful the Biden administration will make further changes to allow tax-exempt bonds to be transferred when states don’t exhaust their annual allotment. That would let other states use them.

“Affordable housing in high-income neighborhoods is critical, as you see cities around the country remain unaffordable,” he said. Koffman added that the tax credit change would be “an easy tweak that would allow more affordable housing.”

Spencer Orkus, managing director at New York’s L+M Development Partners, said it’s important to build affordable housing in high-income neighborhoods to encourage upward mobility.

But if that’s all that is done, poor areas would be left behind, he said.

“You are basically picking a few winners and moving them to middle-income neighborhoods while divesting from low-income neighborhoods that need investment,” Orkus said.

Rasheedah Phillips, a housing attorney at Community Legal Services of Philadelphia, echoed that sentiment. “We have to make sure we don’t divert attention, resources and responsibility to invest back in neighborhoods that were historically disinvested from,” she said.

Phillips noted that Philadelphia landlords routinely deny housing to tenants with rent vouchers, despite a city law that prohibits it. A 2018 study by the Urban Institute found that when contacted about apartment listings, two-thirds of landlords would not accept a voucher.

Thirteen states and 90 local governments have barred discrimination based on source of income to protect families with vouchers, according to the civil rights law and policy organization Poverty & Race Research Action Council. Texas does the opposite: It has a law forbidding municipalities to ban discrimination based on source of income.

In March 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear another challenge brought by the Inclusive Communities Project, which sought to require all landlords to accept vouchers.

In April 2020, the group fired off another lawsuit against HUD, claiming that the nonprofit has shouldered the burden of finding housing for voucher holders because landlords keep turning them away.

Biden has already thrown his support behind a Senate bill from 2019 that would bar discrimination based on source of income, including Section 8 vouchers and Social Security. With the Democrats’ tenuous control over the Senate, however, the measure’s passage is far from guaranteed.

Community choice?

Though the Trump administration repealed Obama’s fair housing rule in July 2020, calling it burdensome and a threat to suburban living, some communities are moving forward with the goals they laid out when it was in place.

“Even though the current administration tried to take the teeth out of it, we’ve continued to abide by it just because it is the right thing to do,” said Marla Newman, director of community development for Winston-Salem, North Carolina — one of the few communities that had a fair housing plan approved by HUD.

“I think we’re morally bound to create ways to address and undo some of the harm that was intentionally undertaken in these communities,” she noted.

But Newman said she hopes the rule is amended to be less “one-size-fits-all” to take into account the unique challenges of different cities and municipalities.

New York City is facing a lawsuit by three Black women from Brooklyn and Queens who repeatedly applied to affordable housing lotteries outside their community districts and were never selected.

In their 2015 lawsuit, the three women allege that as a result of community preference, “entrenched segregation is actively perpetuated, and access to [high-opportunity] neighborhoods … is effectively prioritized for white residents who already live there.”

Andrew Beveridge, a sociology professor at Queens College, conducted a report on behalf of the plaintiffs that found the policy “imposes a sorting process that would not otherwise exist and does so in a pattern that causes material disparities by race and ethnicity.”

A representative for the de Blasio administration, which had tried to keep the report private, declined to comment.

Craig Gurian, executive director of the Anti-Discrimination Center, which is representing the plaintiffs, called it the “Achilles’ heel of liberal, progressive New York to be able to pronounce for everybody else in the country and everybody else in the world, yet be arrogant enough to say ‘our segregation in New York is different.’

“It is not actually complex at all,” Gurian said.

Yet community buy-in on major affordable housing projects — specifically those that entail multiple public reviews — often hinge on guarantees for housing and other benefits for local residents, said affordable housing developer Rick Gropper of Camber Property Group.

“That’s one of the primary questions we get at community boards: How do I get an apartment for the people who actually live in these communities?” he said.

“There needs to be a balance,” Gropper added, “between the need to spread affordable housing and not concentrate it but also provide affordable housing for the people living in the community.