In September, REcoin, a startup that billed itself as the “only cryptocurrency backed by real estate,” was busted for fraud by the U.S Securities and Exchange Commission.

The Las Vegas-based startup had planned to use blockchain technology — a growing list of public records that are encrypted and linked across a network of computers — to support its currency. It launched an initial coin offering (ICO), the equivalent of an initial public offering for digital currency, or tokens, and claimed to have raised millions. But as it turned out, REcoin was duping investors. It never had “any real operations,” had made no investments and misrepresented how much money was raised, according to the SEC.

REcoin is one of many startups looking to leverage blockchain within real estate. And incidents such as this illustrate some of the potential hazards of the nascent technology. While blockchain-based applications are touted as secure, the world of ICOs is a virtual Wild West. It’s a regulatory gray zone, and anyone can launch a token sale with nothing more than a white paper. It’s the same technology that enables the use of Bitcoin — which JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon referred to in September as “a fraud.”

“It’s creating something out of nothing that to me is worth nothing,” the banking executive said. “It will end badly.”

That’s not to say Bitcoin’s underlying technology doesn’t have its benefits. In October, JPMorgan launched a blockchain-based payment processing network, which the bank says will allow for faster and more secure transfers of money. And some property executives, including developer Ben Shaoul of Magnum Real Estate Group, believe blockchain will be a game changer for NYC real estate.

Magnum’s condominium development in Alphabet City will be the first New York site to accept Bitcoin payments. “People call us and say, ‘Hey, I’d like to be able to use my Bitcoin to buy an apartment,’” Shaoul said, noting that he felt it was a no-brainer to offer the option. “When the writing is on a wall, you need to adapt and pivot.”

Eric Hedvat, also of Magnum, added that Bitcoin is more efficient than other payment methods and reduces fees and transaction time. “When you send Bitcoin, it’s peer-to-peer, so you don’t have to go through the bank process, which could take three to four days,” he explained. “With the blockchain and the trusted network, you know in an instant if it was sent.”

But Bitcoin isn’t the only way real estate players make blockchain work for them. Proponents of the technology claim it will allow for smoother cross-border transfers, reduce transaction times from weeks to hours, end data monopolies like CoStar Group and Zillow, and herald a secure globalized real estate market.

“In real estate, blockchain can help a lot in both the title business and in pretty much every aspect of it,” Hedvat said.

Other industries are already experimenting with the encrypted ledger technology. IBM, for example, is using it to monitor its food distribution network and recently released a blockchain-based app for cross-border payments. Similarly, the San Francisco-based startup Propy, an online real estate marketplace, uses blockchain to simplify cross-border transactions. Propy, which launched this year, has already brokered one such real estate deal entirely online. TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington, who is also an investor in Propy, bought an apartment in Kiev, Ukraine, for $60,000 through the platform in September.

“We’re at a great point now,” said Ragnar Lifthrasir, founder of the International Blockchain Real Estate Association (IBREA), which hosted a second annual conference in Manhattan in October. “We’re finally getting strong interest from both sides — software engineers and the big real estate companies.”

Reigning in the wild web

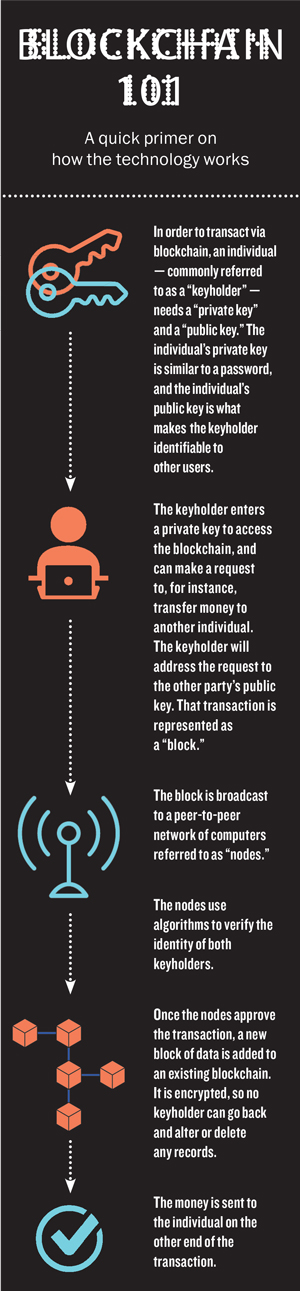

As the name suggests, blockchain is a series of blocks of code, strung together like beads. Because of its linear structure, it creates a transparent and immutable record of every transaction and every access point, which proponents say eliminates some of the obscurity that leads to fraud. Certain so-called keyholders can also access a blockchain from virtually anywhere. These keyholders — all of whom have a unique access code — can share important data with all parties in a transaction, including banks, title companies, governments or even consumers.

One of the most obvious uses of blockchain in real estate is the “tokenizing of assets,” which allows individuals to buy tokens that represent a fraction of a property — or a share of a company that owns a property.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if a cab driver in Kathmandu could own a piece of Manhattan for the price of a cup of coffee?” said Matthew Long, a real estate investor and participant at the IBREA conference. “That’s what blockchain allows.”

A handful of companies outside the U.S., including Atlant, Real and ReiDAO, are claiming to do just that. The problem is that almost none of those firms have actual properties to tokenize. And some have already raised money through ICOs on the promise to build a platform that will allow for tokenization down the line.

But ICOs are a legal morass. And in the last few months, there has been an explosion of digital currency sales.

REcoin was one of several real estate startups to run token sales this summer. In the same time period, Propy raised $16 million through the sale of its “PRO coins”; data provider RexMLS raised $4.5 million “REX coins” to compete with the likes of Zillow and CoStar; and Atlant, which aims to be an “Airbnb, Booking and Expedia killer,” raised $6 million in “ATL tokens.” Stayawhile, a Manhattan-based startup that offers furnished apartment rentals in urban centers like New York and Boston, is beginning its token sale in November.

Though the concept is straightforward, whether or not the sale of tokens should be regulated by a government body remains unclear.

“Are we looking at a security? Are we looking at a commodity? A currency? A collectible?” said Matt Gertler, a digital currencies lawyer and co-founder of Digital Assets Research, adding that each coin or token has to be judged based on what it’s designed to do.

In July, the SEC issued a statement noting that tokens can sometimes be considered securities. That would make those tokens subject to the agency’s oversight and limit who can invest in them. Many firms responded by publishing legal opinions explaining how their own tokens are not securities, citing the “Howey Test” — a set of criteria that defines whether or not an investment qualifies as a security. The test’s main question is whether the returns on an investment are entirely based on the actions of someone other than the investor (if so, the investment would be considered a security).

But not everyone thinks it’s that simple. “In blockchain we’re in the days of the 1990s internet,” said corporate securities attorney Gerald Reihsen with Gerald Reihsen PLLC. “And in ICOs, we’re in 1890s equities.” Though he describes himself as a blockchain enthusiast, Reihsen said he expects to see significant fallout before tokens exit the regulatory gray zone.

Gennadiy Gurevich, a portfolio manager at fund Dominion Capital who invests in real estate startups, said ICOs are a gold mine for speculators. Although there are legitimate players looking to raise money, bad apples are giving the space its shady reputation, he noted.

“It’s an easy way to raise money from a lot of people with nothing more than a white paper and no product,” Gurevich said. “If most of these companies went the traditional [venture capital] route, they would be laughed out of the room.”

A new way to do deals

While blockchain is primarily thought of as a means to create cryptocurrency, it also has other practical everyday applications for real estate, such as changing how properties are sold and how deals are recorded. The technology uses a protocol known as “smart contracts” — a feature of the blockchain-based platform Ethereum, which was developed by a group of programmers in 2014. Smart contracts automatically execute commands when conditions, like an expiration date, are met.

Next year, Stayawhile plans to roll out a smart contract system that essentially acts as an escrow account. The firm launched in 2016 and quickly discovered the challenges for foreigners who want to rent in the U.S., its primary user base. Foreigners are often expected to cough up months of rent upfront to secure an apartment since they don’t have U.S. credit history or a U.S. bank account.

“Even if you’re wealthy and you’re foreign, it’s difficult to rent in the U.S.,” said Stayawhile’s CEO Janine Yorio. “We felt like we could address a lot of these problems with blockchain, because without a solution we really can’t offer our product to international customers.”

In Stayawhile’s new system, a renter can put his deposit in a cryptocurrency wallet that is only accessible to three keyholders: the renter, the landlord and a neutral third party. The landlord and renter will sign a smart contract that dictates when and how the deposit should be released. If those conditions are met, two of the three keyholders need to agree to unlock the deposit. Stayawhile plans to take on the risk and will be responsible for paying the landlord should a renter fail to, Yorio added.

In addition, in the long run, the company plans on using its renters’ transaction data to assess their creditworthiness instead of relying on information from local banks and credit agencies.

The use of blockchain for cross-border transactions is promising, but because the technology is evolving, security is still a major concern, and ensuring the identity of keyholders is crucial. Like Bitcoin, the characteristics of blockchain make it transparent but also anonymous, which could increase its attraction to bad players, according to sources in the data industry.

Reihsen acknowledged that blockchain still shares the same security pitfalls as existing online systems for financial transactions. “The ecosystem around it has all of the weaknesses, and maybe more, than economic transactions in cyberspace generally,” he said, adding that he still thinks that the technology has “remarkable security.”

For startups, just getting the technology to work is a feat, but the greater challenge is determining if their programs or contracts are compliant with the law. In the U.S., there have been incremental steps to legitimize smart contracts. In March, the state of Arizona passed an amendment to the Arizona Electronic Transactions Act in March that expanded the definition of an electronic contract to include blockchain.

In the same vein, Cook County in Illinois approved a title transfer via blockchain earlier this year. The county’s recorder of deeds collaborated with the California-based startup Velox.RE and law firm Hogan Lovells to transfer a property title via blockchain and document it in public records. The aim of the project was to code a legally compliant contract to serve as a template for future transactions.

“We’re not waiting for any laws to pass,” said IBREA’s Lifthrasir, who founded Velox.RE. “We just have to comply with existing laws.”

Other countries are already using the ledger technology to record property sales. The Republic of Georgia teamed up with the software company Bitfury to record land titles on a private blockchain-based platform, as Forbes reported. The Swedish Land Registry and startup ChromaWay have taken that a step further and modeled a program to buy and sell property using blockchain. As of October, ChromaWay is working with a local government in India to implement a similar program, according to news reports.

Ovidio Diaz, a Panamanian lawyer, financial consultant and now blockchain entrepreneur, said adoption of blockchain for real estate transactions was inevitable. “The question,” he noted, “is who is going to lead? Ghana? India? Or New York?”

A technological utopia?

In the early stages of a new technology, pioneers are driven by a sense of possibility, Reihsen said.

“The cycle always begins with technologists who believe they have a global solution,” he said, and although there is value in the technology, “they always overstate.”

“They believe too much in its utopian characteristics,” the attorney noted.

One such optimist is Stephen King, the heir to a small real estate firm in Princeton, New Jersey, and the founder of RexMLS. After joining his father’s business, King found that they were paying more than $10,000 a year to access crucial data that was locked in the vaults of the big real estate data companies.

Now, using blockchain technology, he is trying to create a multiple listing service that can go head-to-head with Zillow, CoStar and the other data giants. Similar to CompStak, RexMLS will give those who contribute data access to the system. The platform, King said, would not be bound by regional or even national lines, and it would allow for a globalized listings service.

“We’re creating a company that connects all of the world’s real estate databases,” King said.

RexMLS has also built a Zillow-like user interface, which in time would allow consumers to search, buy and lease property through the site.

But in order to be successful, the platform would need millions of users to contribute data. In addition, RexMLS ran into a technical hiccup during its token sale in August, and the firm lost the first $1.3 million it raised due to an error that sent the funds to a dead address. The company quickly fixed the error and promised to reimburse its investors, according to King.

“I do like that RexMLS is trying to disrupt,” said Lifthrasir, who has been critical of some ICOs. “They’re not scammers. These are just amateur mistakes.”

But because of glitches like these in ICOs, some blockchain proponents want to draw a line in the sand between the fundraising mechanism and their own applications. In fact, not all startups using the technology issue their own tokens, and, in some cases, they’re not necessary, Gertler said.

“For mass adoption, most people don’t need to transact in these tokens,” Gertler said. “When I use Venmo to send money, I don’t care whether I’m using Venmo’s currency or U.S. dollars, as long as a certain amount of U.S. dollars get sent.”

But even the die-hard enthusiasts know that mass adoption of the technology is far off. Magnum’s Hedvat said it’s unlikely that there will be a huge shift to blockchain in New York or other major markets soon, but the day will come.

“Down the line, in 10 to 15 years, people aren’t going to be looking to the registries or title companies to see what’s going on with their title,” Hedvat said. “They’re going to have it, hopefully, insured in a public ledger that can’t be altered.”

Dominion Capital’s Gurevich said he’s excited but cautious about the future of blockchain. “In terms of proof of concept, we’re already there,” he said. “In terms of this being an everyday application, we’re not even in the first inning.”