It may take a village to raise a building, but it takes only one disgruntled subcontractor to ensnare a project in a legal tug-of-war.

For One57, the 75-story luxury condo tower on Billionaires’ Row, fire sprinklers are at the heart of an ongoing dispute with the developer and project’s general contractor. Federated Fire Protection Systems, which does plumbing, heating and air-conditioning installations, claims that it’s owed $2.1 million for, among other things, installing a sprinkler system from the building’s 21st floor to its roof.

Last October, the company based in Mount Vernon, New York, shot off a lawsuit against the building’s sponsor, Extell Development, and its construction manager, Lendlease, alleging that the firms were delinquent on portions of what was initially a $950,259 contract. Federated Fire is also seeking additional damages caused by alleged delays, change orders and defective contract documents. Extell and Lendlease have filed a motion to dismiss the case, arguing that the company’s contract specifically bars it from seeking damages related to delays.

Contractors and subcontractors are often at odds with one another and their clients. And in New York State, the first step to challenge a disputed bill is to file a mechanic’s lien — a claim against a client’s property that assures a contractor gets paid. The legal fight being waged over One57, which was completed in 2014, escalated from liens that Federated Fire filed against the property in September 2015.

“The placing of mechanic’s liens on construction projects is part of the normal give and take in property development,” a spokesperson for Extell said. “There are currently no material liens against any of Extell’s properties, and any past liens have been settled in the firm’s favor.”

Representatives for Federated Fire, a subsidiary of Tutor Perini Corporation, did not respond to requests for comment and the company’s former owner, Bruce Kelley, declined to comment.

While developers often create limited liability companies to protect themselves when projects fall apart, contractors and subcontractors have far less recourse. Mechanic’s liens are one of the few ways for them to ensure payment. But since liens take little time and effort to file, they can also easily be used as leverage and, in some cases, hold up projects as “ransom” as several industry sources put it. A developer looking to fight a lien may need to go to court — often a costlier option than just paying off the claim.

And when the market slows and construction financing tightens, liens typically become more prevalent, said Tzvi Rokeach, a real estate partner at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel. They also become a greater impediment to securing additional debt, since lenders tend to shy away from properties with active liens on them.

And when the market slows and construction financing tightens, liens typically become more prevalent, said Tzvi Rokeach, a real estate partner at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel. They also become a greater impediment to securing additional debt, since lenders tend to shy away from properties with active liens on them.

Rokeach said developers should be vigilant about the claims filed against their buildings as recession-like headwinds begin to ripple through New York City’s real estate market.

“When the going is good, none of this stuff matters, right?” he noted. “We’re at a point in the cycle now where this could happen. Things go bad, construction projects cease, projects that are in the middle of construction stop, and there’s not money available to pay for folks who have been doing work.”

Who’s the lienest?

This month, The Real Deal assembled a list of private developers and landlords with the most liens filed against their properties in Manhattan and Brooklyn — by dollar volume — over the past five years, based on data from PropertyShark. The top 10 companies on the ranking, led by Rose Associates, Extell and the Howard Hughes Corporation, had a total of more than $100 million in liens filed against their properties as the market went from cool and soft in 2012 to hot and heavy in 2016. Industry sources say the total dollar volume of liens on NYC properties could significantly increase in a prolonged downswing.

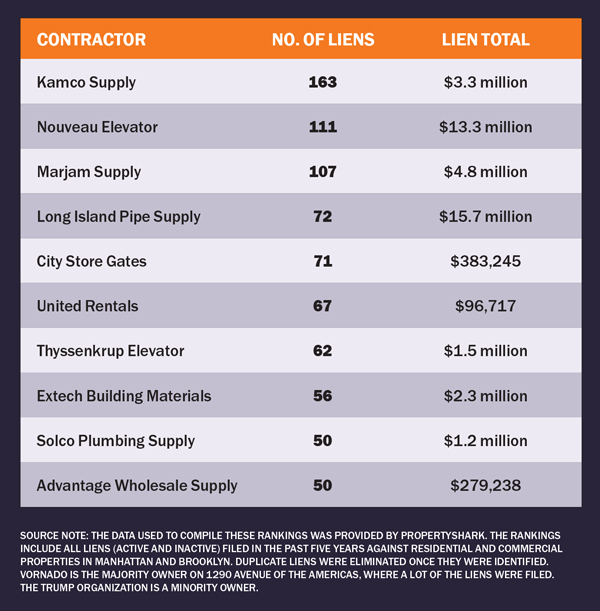

A separate ranking shows the 10 most aggressive filers — by number of liens — in the same five-year period. Those companies include Brooklyn-based building materials supplier Kamco Supply Corp., Brooklyn-based metal and wood supplier Marjam Supply Company, Queens-based elevator repair company Nouveau Elevator, and Brooklyn-based fire protection supplier Long Island Pipe Supply.

The lists provide a rare look at the conflicts that spring up during the development process and the caliber of claims made by contractors and subcontractors who believe they weren’t adequately paid for their work. Since many of these liens were filed against LLCs, some smaller claims may be missing from the top-ranking property owners in cases where they used different company names. Also, as liens are invariably filed against the property itself, the developer or landlord is often listed as the debtor, even if the fault of nonpayment falls to the general contractor or the building’s tenant, which is often the case.

In turn, even as liens help level the playing field, they do so precariously and often create a tangled web of claims. And the fact that liens are filed against the building, regardless of who’s at fault, shows how New York’s mechanic’s lien law can be disproportionately weighed against developers and landlords.

In turn, even as liens help level the playing field, they do so precariously and often create a tangled web of claims. And the fact that liens are filed against the building, regardless of who’s at fault, shows how New York’s mechanic’s lien law can be disproportionately weighed against developers and landlords.

“These are potent weapons,” said James Terry, a partner at the national construction law firm Zetlin & De Chiara. These suppliers and other companies “know that slapping a lien on a project can have real consequences for the owner,” he added.

But while liens are often used as blunt instruments in perfectly standard contract negotiations, they also provide a lifeline for contractors and subcontractors to recoup funds that would otherwise be held hostage. They can also reveal patterns of a developer failing to adequately pay those who work on their projects.

“We value the tool. We’d die without it,” Marjam Supply’s chief operating officer, Carmel Arguelles, said in an email response to questions about the company’s active lien filings. “We file when we have not gotten the correct feedback or the contractor shows a lack of responsiveness to our payment requests.”

Contractor’s first salvo

In most cases, a mechanic’s lien, which remains on the property for a year, serves as a warning shot — the first step in waging a dispute over work that went unpaid. The power to enforce a claim, however, lies with the courts after the contractor or subcontractor files a lawsuit against the property owner to foreclose on the lien.

The foreclosure proceeding could technically force the developer to sell his or her property to pay the debt, but it’s uncommon for such disputes to go that far. Still, liens can serve as a “blemish” on the title of a property, said construction attorney Ronald Francis.

“The lien law provides contractors an enormous power in allowing them to file a lien against a property without showing the basis for the lien,” Francis noted. “All that is required is that they fill out a form.” In New York, those forms require very little information, amounting to a two-page series of fill-in-the-blank questions, he added.

At the same time, contracting companies — which are often small businesses — rarely have access to the same legal resources as the influential and wealthy developers that hire them. For many big property owners, including Rose Associates and Extell, filing a lawsuit or countersuit can take minimal effort.

Still, completely removing liens can be challenge, and having them attached to a property can trip up future sales, insiders say. “A lien essentially puts the world on notice that someone has a claim on that property,” Francis said. “The property is, essentially, damaged.”

The quickest way to remove a lien, of course, is to pay it off. A property owner can also get a surety bond, which transfers the lien from the property to the bond. But that’s a more expensive option, since surety bonds cost 110 percent of the value of the lien. Those who want to prove they don’t owe the amount claimed in the lien usually must go to court.

That’s not to say that workers can just fabricate a bill and collect automatically. Those who knowingly lie about what they’re owed and pursue a claim to the bitter legal end can face significant penalties under New York law. If a court finds that the bill is exaggerated, the entire lien — even the legitimate portion — is voided. The contractor or subcontractor may also be forced to pay their client the inflated portion of the lien.

That’s not to say that workers can just fabricate a bill and collect automatically. Those who knowingly lie about what they’re owed and pursue a claim to the bitter legal end can face significant penalties under New York law. If a court finds that the bill is exaggerated, the entire lien — even the legitimate portion — is voided. The contractor or subcontractor may also be forced to pay their client the inflated portion of the lien.

Proving intent in these cases, however, can be difficult, sources say. Zetlin & De Chiara’s Terry said that subcontractors are only able to make claims on whatever is owed to the general contractor, meaning that if a property owner can prove that they paid a general contractor, the subcontractor is virtually out of luck.

“The derivative nature of the lien law is designed to assure that the owner doesn’t end up paying twice for the same thing,” he said. “The general contractor is almost always bound by the owner to keep the property lien free. They are often the ones who are in the middle of this.”

When liens are filed, however, it’s rarely a clear-cut case of a developer stiffing contractors — or a greedy contractor trying to shake down a client. Disagreements can crop up over many different issues in construction. Some of the most common disputes occur over change orders, incomplete work and situations where a general contractor finishes a job without paying subcontractors.

“It’s a last resort for us,” said Frank Sciame, head of his eponymous construction company, Sciame Construction. His firm has both filed liens and had them filed against it. “It’s something to be taken very seriously,” he said. “You shouldn’t file a lien unless you feel strongly about your position.”

Sciame noted that his company will sometimes file a lien if it seems the property owner is having financial difficulties and there’s any indication that he may not pay. At other times, the circumstances of a project change and filing a lien is just a natural precautionary measure, Sciame explained.

Topping the lists

In many cases, the developers and landlords with the most liens against their properties accrued them on one or two high-profile projects.

Rose Associates, the lead developer on the conversion of 70 Pine Street from an office building to luxury condos, racked up $24 million in liens on the landmarked tower in the five-year span, the PropertyShark data shows. The claims stemmed from disputes with a construction management company, a moving company and an architecture firm. A representative for the company said each of those liens have since been resolved.

Extell accumulated $16.5 million worth of liens in the same time frame — mostly against One57. The largest of the claims against the developer’s properties was filed by the Ozone Park-based electrical contractor Five Star Electric Corp., another Tutor Perini subsidiary, for $14.8 million. It doesn’t appear that the claim ever became the subject of a legal dispute, based on court records, and the Extell spokesperson said the lien has been resolved. Five Star Electric, meanwhile, ranked among the top lien filers by dollar volume, with $35 million among 16 claims in the past five years. A spokesperson for the company did not return calls seeking comment, and representatives for Tutor Perini declined to comment.

The Dallas-based developer Howard Hughes racked up $16 million in liens on its New York City projects over the past five years, mostly filed against its 94 South Street, the redeveloped Fulton Market Building, which is now home to a movie theater. A representative for the company said most of those liens have been resolved.

70 Pine

Similarly, the bulk of the $11.3 million in liens filed against Taconic Investment Partners’ properties are connected to the real estate firm’s 34-unit condominium project at 71 Laight Street, known as the Sterling Mason.

“The recent liens filed against the sponsors of a single project on Laight Street are the subject of ongoing litigation,” a spokesperson for the firm said. “We strongly dispute the claims made by the project’s construction manager and look forward to addressing them in court.”

Topping the list of filers was Kamco, a residential and commercial building material supplier, which filed 163 liens, totaling $3.3 million, in the five-year period.

Marshall Stern, an attorney for the ceiling tile supplier, told TRD that his client initiated a high volume of liens in the past five years because it has a high volume of business and “insists on being paid on time.” He said developers and contractors can be “deadbeats” but noted that sometimes concerns outside of the project take priority.

“Christmastime comes along, and you can buy presents for your kids and your wife — or you can pay your material supplier,” Stern said. “There’s always that personal part in there. But sometimes there’s a champagne case and a beer budget.”

Kamco, which has offices in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Long Island and New Jersey, is pursuing a class-action lawsuit against construction subcontractor Nastasi & Associates for allegedly failing to pay $975,161 on a $1.3 million bill for ceiling tiles and other building materials at 150 East 42nd Street. That case demonstrates how liens can evolve and target other third parties rather than the project’s developer or landlord.

Kamco, which filed a mechanic’s lien for the work in April 2015, claims that Nastasi used payments from the general contractor and property owner to pay other companies, when the money should have gone to the material supplier. The class-action lawsuit is open to those who provided work or materials to Nastasi on several projects, including Madison Square Garden, Trump Tower, 200 Park Avenue and 10 Columbus Circle, according to court documents.

Federated Fire, which is waging at least two ongoing lawsuits against developers for alleged unpaid work, filed roughly 41 liens totaling $4 million in the past five years. In addition to its complaint over payment for One57’s sprinkler system, the company has an ongoing case against Alexico Group and Lendlease for work it performed at 56 Leonard Street, a 57-story condo project in Tribeca. The lawsuit, filed on March 6, 2016, seeks roughly $3.4 million in damages related to an alleged unpaid contract balance and wrongful termination.

In that case, Federated Fire makes similar claims to the ones in its complaint against Extell and Lendlease. The company also alleges that the general contractor and Alexico wrongfully replaced it on the project after providing “defective” contract documents and rushing it to complete work that wasn’t initially specified.

The Federated Fire lien is one of at least 15 filed against Alexico’s properties in the past five years, all of which pertain to 56 Leonard and total nearly $8 million. Kelley, then-president of Federated Fire when the company was hired to work on the project, also declined to comment on the Alexico and Lendlease case. Both lawsuits were filed after he sold the company to Tutor Perini in 2013.

Gerald Bianco, senior vice president of project management and construction at Lendlease, said that all the liens are related directly to subcontractors that were fired from the job and therefore were not “Alexico’s doing or responsibility.” He said 14 out of the 15 liens were related to Lendlease terminating the New Jersey-based general contractor Collavino Construction from the job and have been bonded, so they no longer encumber the project.

The best defense?

In the case of two liens filed by architect Robert A.M. Stern this year, the claims were largely a preemptive measure. Stern’s company filed two liens against the Chetrit Group —totaling $900,329 — one month after news surfaced that the developer decided to abandon a condo conversion at 550 Madison Avenue. Those liens, according to a spokesperson for Stern, were resolved promptly.

In some cases, though, architects are forced to chase after clients for their payment. In 2014, Gene Kaufman filed a lawsuit against the then-owner of the Hotel Chelsea, King & Grove Hotels, alleging that he was owed some $80,000 in unpaid fees. Kaufman was kicked off the troubled project in 2013, after King & Grove split with co-owner, the Chetrit Group. King & Grove hired Marvel Architects to replace Kaufman, who accused the firm of continuing to use his design after he was booted from the project. The lawsuit was ultimately settled.

During a 2016 presidential debate, contract disputes were brought into focus when Hillary Clinton tore into what she said was Donald Trump’s habit of stiffing employees on their paychecks.

She noted that one contractor in particular — the architect who worked on the Trump National Golf Club in Westchester, New York — was in the audience. Andrew Tesoro, the head of a small firm based in the city, collected only a portion of what he was owed for work he completed on the golf course’s clubhouse: $25,000 of $141,000 in outstanding bills.

“It’s a beautiful facility. It immediately was put to use,” Clinton said at the time. “And you wouldn’t pay what the man needed to be paid when he was charging you.”

Tesoro told TRD that he hadn’t filed a lien on the property.

“I decided not to pursue an action because the Trump Organization made it clear that they would fight me tooth and nail and it would cost more than it’s worth,” he said. “It was a unique situation. Generally, I’m pretty savvy, but I got snookered.”

Gregg Pasquerrelli, a founding principal at the high-profile firm SHoP Architects, noted that while his company very rarely files liens, it’s comforting to have the option.

“Knowing that that’s something you can do is incredibly important because you see a lot of people who would not pay their bills,” he said. “Some of them even become president.”