Red Hoek Point would seem to have it all.

Plans for the Thor Equities Brooklyn office project call for trendy “heavy timber” construction and a waterfront location with views of Lower Manhattan and the Statue of Liberty from its environmentally friendly roof. And the two planned buildings totaling about 800,000 square feet, designed by Foster + Partners, will be close to ferries, water taxis and Citi Bike stations.

But what the Red Hook development doesn’t have is tenants — a recurring theme with several new and proposed office projects in Brooklyn’s rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods.

Numerous data sources show signs of a slowdown in office lease deals and related activity in the borough. And developers, brokers and lenders who spoke to The Real Deal gave an overall cautious outlook on the latest wave of office space coming to the trendy northern and western parts of Brooklyn. The latest doubts add to several warning signs industry sources told this publication about more than a year ago.

“I am concerned a bit about supply,” said George Doerre, a vice president at M&T Bank who works on commercial real estate debt deals. He said the bank has become increasingly selective about the location of Brooklyn office projects it lends on.

“The thought is, sometimes residential is a little easier to absorb because you only have to move a couple hundred or a couple of thousand square feet at a time,” Doerre added, saying that there’s a market for office space in Brooklyn, as long as “people don’t aim too high in rents.’’

Rising caution signs

As of now, the only place to see Thor’s Red Hook development is on the project’s website, which describes it as “a revolutionary office campus.”

Joseph Sitt’s real estate firm has continued to promote Red Hoek Point — a take on the Roode Hoek name that 17th-century Dutch settlers gave the area. The project is due for completion in 2019, according to several reports, and Thor has been working on getting the required city permits.

But some local observers don’t think the developer is trying that hard. Jerry Armer, former landmarks and land use chairman at Brooklyn Community Board 6, said he’s “pessimistic” that the project will ever see the light of day.

One source with knowledge of the matter, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said Sitt is torn between developing the site as proposed and building a warehouse instead. A Thor spokesperson declined to comment.

If the developer goes the industrial route, it could be a telling sign for the borough’s office market. The much-hyped wave of demand for technology and creative space that was expected to hit Williamsburg, Gowanus and Downtown Brooklyn just hasn’t materialized — at least not yet. And whether next year will bring a notable change to the market is anyone’s guess.

So far, the largest new Brooklyn office lease in 2018 is the NYC Department of Records and Information Services’ 133,000 square feet at Industry City in Sunset Park, just south of Red Hook, according to Colliers International. That deal closed in the second quarter.

The second-largest lease is Brooklyn Lab Charter School’s 82,000 square feet at 77 Sands Street in Dumbo, which closed in the first quarter. That space is part of the former Jehovah’s Witnesses’ printing complex, which Kushner Companies, LIVWRK and RFR Holding bought in 2013 and converted into a mixed-use campus branded Dumbo Heights.

But the arrival of government recordkeepers and a charter school is a far cry from the advent of tech companies that would otherwise drive office demand and boost rents.

A “barrier across the East River seems to be affecting some tenant migrations,” said Craig Caggiano, Colliers Interntional’s executive director for the tri-state region.

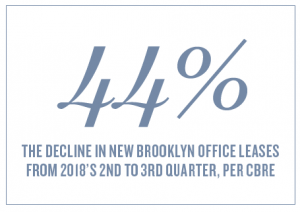

A third-quarter CBRE report on the market called demand for Brooklyn office space “tepid” and identified just under 200,000 square feet in the borough as newly leased — a 44 percent decline from the previous quarter. Brooklyn’s office availability rate, meanwhile, was nearly 20 percent in the third quarter, and the global brokerage cited a “robust” number of new office projects expected to arrive on the market by 2020. Midtown Manhattan’s availability rate, for comparison’s sake, was 11.1 percent, and Lower Manhattan’s was 14.3 percent in the same period. (For its availability rates, CBRE counts properties that are vacant as well those that are soon to be freed up and already being marketed for leasing within 12 months.)

“The influx of tenants will need to gain momentum in order to help absorb the abundant space in the pipeline,” the firm’s third-quarter report noted.

Today, Brooklyn is home to 55 million square feet of office space, which exceeds the 46 million square feet in Philadelphia’s central business district, per Colliers’ research. And as of Sept. 30, there was roughly 6 million square feet of new Brooklyn office space in the works — with 80 percent of that to be built or renovated by 2022.

Across the East River, Manhattan has about 14 million square feet of office space in the works.

“This is the most development we’ve seen [in Manhattan] since the 1980s, but an underreported story is that relative to market size, there is much more going on in Brooklyn,” Caggiano noted. “What we don’t see is a lot of migration from Manhattan to Brooklyn. We see a growing diversity of the Brooklyn tenant base. But in terms of the size [and] the number of deals, you can basically track them on one hand every quarter.”

“A different ecosystem”

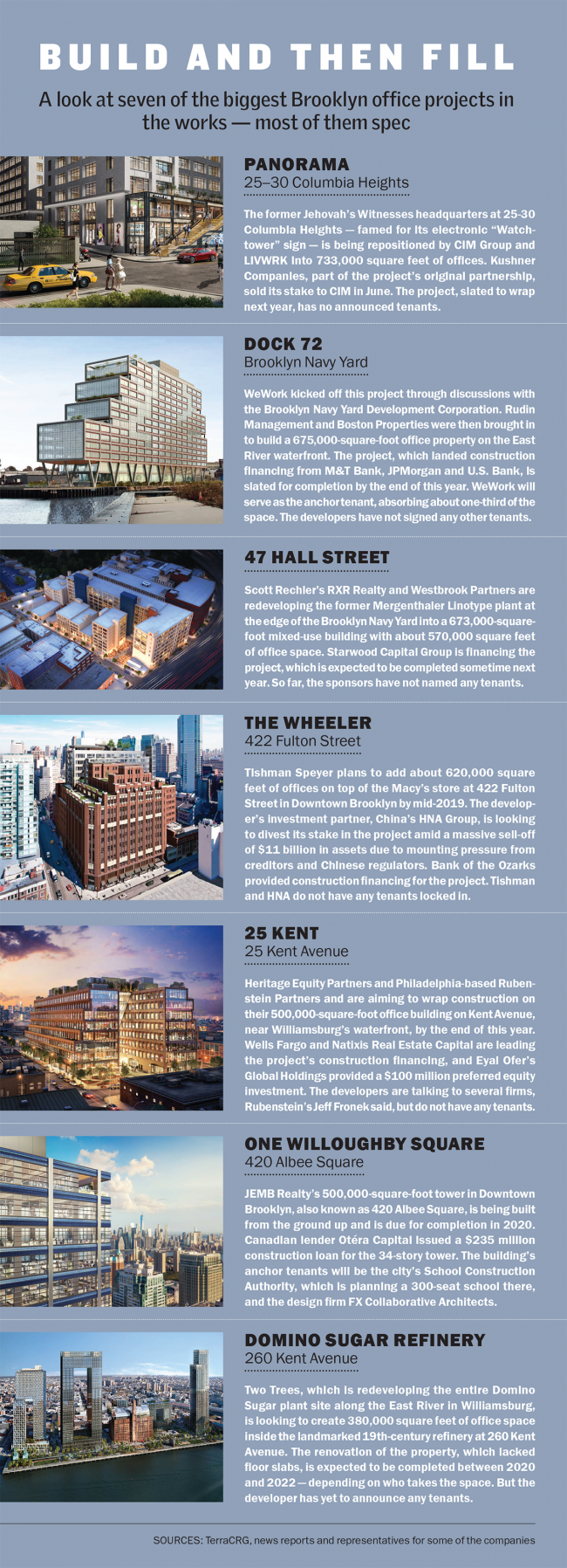

The pipeline for new Brooklyn office space includes some of the city’s most closely watched projects.

Among them is Dock 72, the 675,000-square-foot office project at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which is due for completion in December. Boston Properties and Rudin Management co-developed the 16-story building in collaboration with WeWork, which will occupy a third of the space as its anchor tenant. M&T, JPMorgan Chase and U.S. Bank provided a $250 million construction loan for the $380 million project.

Dock 72 is the first building to be developed from the ground up for WeWork, and the co-working giant played an active role in initiating the project through discussions with the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation. It also had a strong hand in the design — including space for an organic coffee bar, an outdoor basketball court and a rooftop conference center, among other amenities.

But the developers have not announced a single additional lease at the waterfront office property, and WeWork’s business model depends on the company finding other parties to fill its co-working spaces.

But the developers have not announced a single additional lease at the waterfront office property, and WeWork’s business model depends on the company finding other parties to fill its co-working spaces.

Developer Michael Rudin said he’s confident that Dock 72 will have a healthy occupancy level in the near future. “Whether it gets filled tomorrow or in two years is anybody’s guess, but the demand is there,” he said. “We still fully believe that young, entrepreneurial tech companies will be major [tenants] for our project and others in the community.”

While Dock 72 has garnered a lot of attention from the tech community, M&T’s Doerre said Brooklyn is still far behind Manhattan when it comes to luring large corporate tenants.

“You’re probably not going to see a 300,000-square-foot law firm lease,” he noted. “It’s a different ecosystem. You have to be comfortable with the tenancy, which is looking for that Brooklyn cool.”

Representatives for JPMorgan and U.S. Bank declined to comment.

Near Williamsburg’s waterfront, meanwhile, Toby Moskovits’ Heritage Equity and Philadelphia-based Rubenstein Partners are developing 25 Kent, a 500,000-square-foot project that’s also due for completion by the end of this year. But to date they have not announced a single tenant.

Success with office leasing is a matter of having a completed building to show prospective tenants, said Jeff Fronek, Rubenstein’s director of investments.

Fronek said he’s had conversations with several prominent firms interested in leasing space at 25 Kent and is eager to show them the finished product.

“Of course, it’s not done till it’s done,” he said, “but we’re confident about where we’re at.”

Tightening the spigot

Regardless of any cranes perched in the borough, Real Capital Analytics data shows that Brooklyn’s office construction activity has already started to wane — a trend that could ultimately work to the advantage of owners of existing buildings with unleased space.

Developers completed 947,000 square feet of new office space, valued at about $604 million, during 2018’s first quarter and another 602,000 square feet in the second quarter, according to figures from the research firm.

But only 56,000 square feet of office space wrapped in the third quarter, and while construction activity is expected to rise to an estimated 641,000 square feet in the last three months of the year, RCA projects that no office space will be added in 2019’s last quarter or 2020’s first quarter.

Other data indicates that financing activity for Brooklyn office properties may have also peaked. Last year, the total value of Brooklyn’s office debt deals climbed to nearly $2 billion, up from $1.84 billion in 2016 and $1.27 billion in 2015, according to the loan data firm CrediFi. For this year’s first three quarters, however, the firm has tracked just $1.15 billion in loan originations (noting that its data for September is preliminary.) In order for 2018’s tally to at least match last year’s total, loan originations in the fourth quarter would likely need to reach $850 million.

Bankers and other lenders are treading much more carefully now, multiple sources on the finance side told TRD.

“We’re starting to see a plateau [in demand, and] we’ve become more cognizant of the supply issue,” said Tony Fineman, a managing director at the nonbank lender ACORE Capital based in California. Last year, his company funded the repositioning of 10 Jay Street in Dumbo from a warehouse to office space. Going forward, Fineman said, “We’re going to be cautious.”

One banker, who asked to remain anonymous, said developers are eager to mirror the success that Joseph Cayre’s Midtown Equities achieved with Empire Stores, 19th-century warehouses on the Dumbo waterfront it converted into 443,000 square feet of offices, shops and restaurants. Empire’s now fully occupied office space includes the advertising firm 72andSunny, furniture retailer West Elm and aerospace manufacturer United Technologies’ digital hub.

But lenders aren’t banking on everyone replicating that formula.

Aaron Appel, JLL’s head of debt and equity finance in New York, said Brooklyn is “really a tale of two markets” — one located close to subway stations and with the best of amenities, and the other situated in less desirable locations with fewer bells and whistles. Appel helped arrange financing for the conversion of the former Dime Savings Bank in South Williamsburg into office, retail and residential space as well as the ground-up development of One Willoughby Square, a 34-story office tower in Downtown Brooklyn. He said those projects, which are comparable to high-end Manhattan office space at lower asking rents, will do well over the long term.

Sean Reimer, a principal at the real estate investment firm Square Mile Capital, also expressed optimism and said he’s comfortable with the current level of demand for Brooklyn office space. Square Mile provided a $150 million construction loan to developer Tavros Development Partners and Charney Construction & Development for their Dime conversion project, which will include about 100,000 square feet of office space.

Reimer said he views the slowdown in demand for Brooklyn office space as temporary and noted that his firm is seeking out other promising projects in the borough across multiple asset types. “Every project needs to be evaluated on its own merits,” he said. “Generally, I believe in the long-term viability and attractiveness of Williamsburg.”

The employer equation

As demand for the borough’s residential space has expanded in recent years, some developers speculated that employers might wish to capitalize on Brooklyn’s allure by leasing offices there to infuse their brands with a hip, youthful aura.

Vice Media and online merchant Etsy paved the way forward.

Recently, a handful of crypto and blockchain startups opted for the borough, including Bushwick-based ConsenSys, founded by one of the creators of the web-based currency Ethereum.

And last year the fashion company Lafayette 148 New York signed on for 96,000 square feet in Building 77 — a 1 million-square-foot shipbuilding facility-turned-office in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Not only did Lafayette 148 exit Manhattan, it left behind the very 148 Lafayette Street address in Soho it was named after.

The whole calculus could radically change if Amazon decides to build its second headquarters in the borough. New York City is one of 20 finalists competing to host what’s being called HQ2, and the city’s proposal offered four locales, including Downtown Brooklyn. A report from the e-commerce giant said it plans “invest over $5 billion in construction and grow this second headquarters to include as many as 50,000 high-paying jobs.”

But companies contemplating a relocation to Brooklyn need to engage in a bit of cost-benefit analysis. Starting next April, a 15-month shutdown of L train service between Manhattan and Brooklyn will complicate matters for many commuters to Williamsburg, Bushwick and other neighborhoods. And the lack of new tenants in some of the hippest pockets of the borough can become a deterrent for other companies going forward, sources say.

In 2018’s third quarter, “leasing activity was particularly muted in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Williamsburg/Greenpoint … with both submarkets failing to record any sizable lease transactions,” CBRE’s third quarter report noted.

JLL’s Appel, meanwhile, voiced concerns about some of the existing office properties in the borough.

“There are a number of assets in Brooklyn that are of mediocre design and not situated around enough public transportation to really have any demand drivers,” he said. “Those projects will struggle.”