Boaz Gilad got up from his desk.

“Let me just close the window,” the Brookland Capital founder said. But it wasn’t because of the weather — the sunny, 65-degree morning was one of the nicest New York had seen in months.

“They’re making noise,” he said above a series of squawks.

Gilad keeps four Quaker parrots in a massive birdcage on the outdoor stone patio of Brookland’s Bedford-Stuyvesant headquarters. A large picnic table sits at the center, with a pizza stone and grill off to the side, making it a popular spot for the company to host parties.

With a well-stocked wine fridge, a vintage Ms. Pac-Man arcade machine and blue-light fish tank along with the patio, the firm’s Malcolm X Boulevard office looks more like that of a tech startup than an established real estate company.

“I want to be not just relevant but at the edge, because I think that’s what made Brookland what it is,” Gilad said.

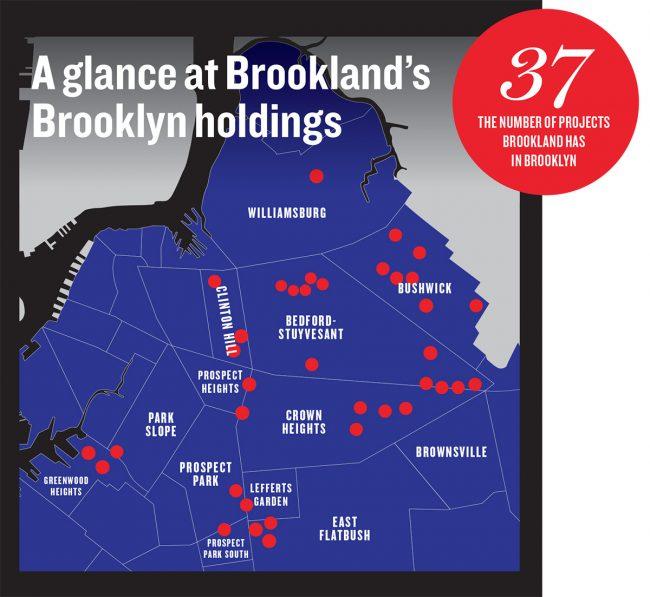

Since he and his former partner, Assaf Fitoussi, founded Brookland in 2012, the firm has delivered more than 2,000 units of housing to Brooklyn (Gilad bought out his partner’s 50 percent stake in the firm for an undisclosed amount last year). The company currently has 37 developments in the borough, according to an analysis by The Real Deal, making it the most prolific developer in Brooklyn by number of projects. Gilad credits the firm’s “early entry” into the Brooklyn market and desire to stay on the vanguard of the industry for Brookland’s success.

He’s still a bit surprised at how popular Brooklyn has become since he started his real estate career. Gilad recalled going to networking events in the early aughts, when the perception of the borough was far different than today.

“As a Brooklyn developer, no one cared, and I went back to the shrimp cocktail,” he said. “Now when you go into events in Brooklyn, oh my gosh, they’re everywhere. Brooklyn is at a tipping point.”

The borough no longer draws in residents because of its proximity to Manhattan, but because it’s a place where people want to live, Gilad said, and in that sense, he believes it still has room to grow.

But as Brooklyn continues to evolve into a highly sought housing destination, it is unclear whether Brookland’s strategy of building dozens of midsize projects throughout the borough will allow the company to “remain at the edge.” Developers continue to set records with the amount of concessions offered on rental product, according to a recent Douglas Elliman report, with more than 51 percent of transactions seeing some type of incentive offered. And the average sales price for Brooklyn condos was roughly $1 million during the first quarter of 2018, down 13.2 percent from the first quarter of 2017. The absorption rate dropped as well, falling to 2.5 months from 2.7 months over the same time period.

Whether or not Brookland changes its strategy going forward will largely depend on external forces, namely how the lifestyles of millennials, its core clientele, change as they settle down and have children, according to Ofer Cohen, founder and CEO of the Brooklyn brokerage TerraCRG. (The two first met in Jerusalem nearly three decades ago and bumped into each other again about 14 years ago at a playground in Park Slope, where they realized they were both in the real estate industry.)

“They have a pipeline of development sites that they didn’t even break ground on yet, so they’re already on track to continue at the same pace,” Cohen said. “The real question is, how will the market change?”

From scripts to blueprints

Long before Gilad, 46, became a full-time developer, real estate was a means to an end.

The Jerusalem native, who came to New York 24 years ago, majored in philosophy at Hunter College and initially got into the industry as a way to help support his and his wife’s acting aspirations. He said he made his first acquisition in 1999 — a two-family building at 226 Gates Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant — and worked as a landlord in Brooklyn before he was a developer. However, he soon found he enjoyed the business enough to pursue it full-time (his wife is now a Broadway producer and they live in Prospect Heights with their children).

Boaz Gilad

The developer said he does not miss the acting world but credited it for helping him get used to rejections. This steeled him for a career in real estate, where he was pleasantly surprised to find that the “no’s” actually came less frequently.

Gilad met Fitoussi by coincidence about a decade ago in 2009 at St. Vincent’s Hospital, where both of their children were born on the same day. They started working together in 2011 and officially started Brookland a year later.

The two split up last year, and Gilad told TRD at the time that this “was done on great terms” and Fitoussi was “departing in good friendship.” His takeover was due to the company shifting its focus more toward midsize multifamily projects.

Brookland currently has 47 employees. Its executive team includes COO Craig Cohen, who came from the food industry, CFO Noa Poran, who previously worked at Ernst and Young, and Vice President of Construction Aviv Ben Avi, who worked at Shuster Construction and Israeli construction company Danya Cebus.

Having several projects going at once has been a hallmark of Brookland for years, and Gilad has maintained this strategy since assuming full ownership of the company. It has eight developments each in Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant, six in Flatbush, five in Ocean Hill, four in Crown Heights, two in Gowanus and one each in Sunset Park, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights and East Williamsburg. The company’s portfolio comprises roughly 85 percent condos and 15 percent rentals, with a total condo sellout of roughly $500 million.

Brookland’s closest competitors in Brooklyn as of March were Urban View Development Group, which had 34 projects, and All Year Management, with 19.

None of Brookland’s projects are particularly large, however — the firm has roughly 437,000 square feet in the works in Brooklyn. While Two Trees Management is working on its 2.9 million-square-foot Domino Sugar refinery site in Williamsburg and the Chetrit Group is in the middle of a 556,164-square-foot development at 9 DeKalb Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn, Brookland’s largest project is a roughly 48,000-square-foot condo project with 68 units in Flatbush at 88 Linden Boulevard.

David Schwartz, co-founder of Slate Property Group, said he thought it was “amazing” that Brookland has been able to handle so many developments at once, and he doesn’t know any other firms that deal with such high volume. He does not think that keeping the projects on the smaller side makes it easier for the company to do so many.

“If you’re doing a residential building, if it’s 30 units or 100 units, I don’t think it’s three-and-a-third times as much work to do the 100 units,” he said, “so I think it’s pretty impressive to be able to manage that many jobs.”

Although the term “micromanaging” is generally used to describe an overbearing boss, Gilad sees it as one of Brookland’s core strengths. He doesn’t think the company could handle doing so many projects without it.

During the 2008 financial crisis, Gilad said, the first things to go were the bankers and the general contractors — meaning he had to essentially take the construction of his projects into his own hands.

“I had to learn, without any knowledge, to become a contractor during the crisis,” he said, “so [I had to] literally go and pick up guys at the entrance to Home Depot and pick up material in the back of my old Saab and go to the building.”

Now, Gilad said, he enjoys being able to hop into his car and visit his worksites, which allows him to keep closer tabs on how the work is proceeding and how the money is being spent.

This philosophy may ultimately lead to another branch of Brookland, as Gilad said the company is now thinking about developing its own construction arm to build projects itself.

“There’s good and bad to it like anything else,” he said of micromanaging. “The good thing about it is we’re in control, and we know what we’re doing.”

Early adopters

Although Gilad is proud of what his company has achieved over the years, he acknowledged that part of its success is due to luck. They came to Brooklyn early, and the borough has since become one of the most sought-after real estate markets in the country.

“It’s the hottest place to be, and we were just lucky,” he said. “We bought a lot of land at areas where people didn’t know what they were sitting on.”

Cohen echoed this sentiment, saying that Brookland was able to find a niche early on in the Brooklyn market, and its intense familiarity with the borough has allowed it to maintain a strong presence there.

“People that came in from outside the market usually tried to impose on the Brooklyn market something that they learned somewhere else,” he said. “Boaz didn’t try to do that. He tried to do something that was homegrown. That was successful, and then he said OK, well, how can I scale that business model?”

The company was also one of the pioneers in raising money on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, acquiring $34.5 million through a bond offering in 2014 and about $20 million in a later round of funding. It plans to raise additional money on the exchange as well.

Gilad said the company was able to do this because it got in early, and he thinks that there would not be room for it on the exchange if it tried to break in now.

“After us, huge companies came in, so Related and Extell and Moinian and all those big, big companies,” he said. “The window closed. If you’re a company our size and you want to do it today, I don’t think you can really come and do a public offering.”

Because Israel’s economy is relatively small, the bond market allowed Brookland to act as a larger company than it actually was, Gilad said. It also allowed Brookland to spread risk around more after suffering heavy losses during the financial crisis.

“You want to have sources of equity in different places,” he said. “So, if there’s a crisis locally, you can go and raise money from somewhere else.”

He framed Brookland’s move to the stock exchange as a long-term decision that will supply the company with money as it grows, but he noted that 2017 was a tough year. Revenue fell to about $24 million from about $68 million in 2016, which he said was because the shift from smaller projects to midsize projects made it hard to deliver enough inventory.

Eli Karp, founder and CEO of Hello Living, said he has known Gilad for about five years and attributed his ability to work on so many projects simultaneously to his access to money and strong team. But he added that the downside of working on several smaller projects — instead of larger ones that have more potential to change a neighborhood — is that they end up looking somewhat uniform.

“I would call it more cookie cutter-style buildings,” he said of Brookland’s projects, “because [Gilad] keeps going, and he’s forced to do it because he has to turn over the money [from his investors] faster.”

The money from Israel does not have a huge impact on how Brookland structures its business, as it is only being used to finance three projects, according to Gilad: 15 Somers Street, 189 Cooper Street and 929 Atlantic Avenue.

Gilad said that Brookland tries to make all of its projects distinct, tailoring them to different clients and different neighborhoods. However, he acknowledged that it is not always able to pull this off.

“I believe we are succeeding. Are we succeeding 100 percent? No,” he said. “But I think we succeed in most cases.”

Chasing millennials

Gilad said Brookland only owns a few sites it has yet to develop, as it is still waiting for plans to be approved by the city. He took a break from buying Brooklyn properties about two years ago because prices became too expensive but plans to dive back in again and buy more soon, as the numbers have started to calm down a bit.

Brooklyn land prices dropped to $248 from $262 per buildable square foot last year, returning to 2015 levels, according to data from Ariel Property Advisors. This was the first time since 2012 that land prices dropped year over year.

While acknowledging that “every developer” would love to build a massive project like City Point in Downtown Brooklyn, Gilad said he is not fixated on making his mark with a project of that scale and would only look to do so if the numbers made sense.

One advantage of working on smaller projects is that the risk is more spread out, so if something bad happens at one site, it won’t necessarily do too much damage to the company’s bottom line, Schwartz said. New York also has more opportunities for smaller projects because of the city’s limited land space.

Disadvantages basically boil down to money, as companies have to take care of costs like superintendents, Department of Buildings filings and project managers for each of their new projects, not just one, according to Schwartz. “You lose somewhat on economics of scale,” he said.

But still, Gilad said he’d “rather do 10 buildings with 50 units versus one building with 500 units.”

He said his favorite area in the borough right now is Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, citing its neighborhood feel and proximity to Prospect Park. The company is at work on six projects there, according to its website: 227 Clarkson Avenue, 75-77 Clarkson Avenue, 154 Lenox Road, 88-92 Linden Boulevard, 56 East 21st Street and 15-19 East 19th Street (TRD’s analysis classified these projects as being in Flatbush).

He is also excited about his company’s plans for 257 Washington Avenue in Clinton Hill, the former location of St. Luke’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, where Brookland intends to start construction on townhouses over the summer.

“We’re taking this unbelievable, beautiful church and chopping it into eight large townhouses,” he said.

But one thing that has been challenging, Gilad said, is his ability to relate to his customers. When he first got started, he had far more in common with his clients.

“I constantly read articles and am interested in what millennials are interested in or what hipsters are because I’m not,” he said. “I’m 46 years old with three kids.”

But instead of focusing on Brooklyn indefinitely, Gilad said, what’s more important is serving his core clientele of millennials.

“I see us as Brooklyn-style developers,” he said. “So if Ohio or New Jersey or Denver gives us an opportunity to do that, we’re totally exploring those options.”