When George Schneider decided to sell his home this spring, Opendoor made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

When George Schneider decided to sell his home this spring, Opendoor made him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Schneider had paid $76,750 for his three-bedroom stucco house in the Phoenix suburbs a decade earlier. Opendoor, the iBuying startup backed by SoftBank and Lennar, was willing to pay him $225,000, all-cash.

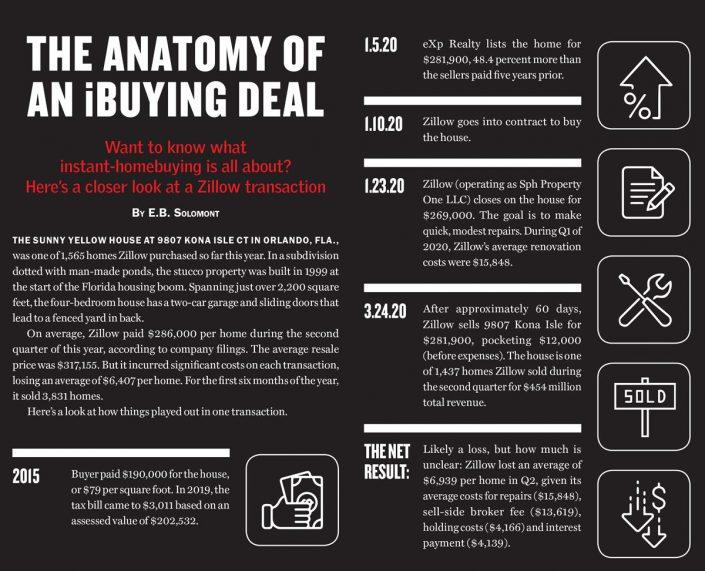

The deal closed in August. After a paint job and minor repairs, Opendoor turned around and sold the property for $265,000, making $40,000 before expenses. But $40,000 doesn’t go too far when you’ve got to pay broker fees, taxes, interest and holding costs.

iBuying, the catchy handle for algorithmically driven instant-homebuying, is one of the biggest wagers seen in the residential real estate industry over the past five years. Established giants like Zillow have dumped hundreds of millions of dollars into developing their platforms, while startups like Opendoor and Offerpad have relied on venture capital firepower to compete. Last year, iBuyers purchased $8.1 billion worth of homes — so far just 0.5 percent of the U.S. housing market but twice the volume of the year prior. Since 2015, the number of players in the space has gone from two to two dozen. The goal is a lofty one: to institutionalize the U.S. single-family home business, one of the world’s largest and most fragmented marketplaces.

Sellers get speed and the certainty of an immediate offer, benefits for which many give up the premium they could have got from the standard selling process. But for iBuyers, the financial burden is tremendous, and the path to profitability deeply uncertain. Last year, Zillow lost more than $300 million on iBuying. Opendoor, which is set to go public in a $4.8 billion merger with a blank-check company, has lost nearly $1 billion since it launched in 2013.

Read related story: This man wants to make your home a commodity

In 2019, Glenn Kelman, CEO of online brokerage Redfin, which had dipped its toes into iBuying, called the business a “race to the bottom.” And increased competition could make profitability even more unlikely.

“When those guys [iBuyers] start competing and making offers,” said Gilles Duranton, a real estate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, “the seller is going to sell to the iBuyer with the best offer, to whoever is making the biggest mistake on price.”

From eBay to Amazon

Homes are traditionally valued using “comps,” or an analysis of how much similar homes in the same area traded for. Comps, iBuyers argue, fail to take into account the unique characteristics of each property. iBuying uses algorithms to generate what they claim are far more accurate assessments of value by analyzing hundreds of different data points — everything from whether a home has granite or Formica countertops to the size of a home’s outdoor space.

The iBuyer will then make an offer for the home based on this value and collect fees of between 6 and 10 percent. The aim is to make minimal necessary repairs and quickly sell the home at a profit.

“Agents who dismiss the iBuyers as ‘flippers,’ I think they’re doing that at their own peril,” said Lane Hornung, founder of zavvie, a Denver-based startup that aggregates different iBuyer offers for sellers.

Brendan Wallace, a managing partner of real-estate focused Fifth Wall Ventures and an investor in Opendoor, described the current U.S. residential landscape as the “largest peer-to-peer market on earth.”

“It’s a gigantic eBay for homes, the most expensive asset most consumers ever purchased,” Wallace said in May. “And as a result, the information, the transparency, the speed of transactions are all suboptimal.” A company like Opendoor, Wallace said, “can capture data, provide transparency around the sale. So you just have a higher level of quality, a higher level of experience.” iBuyers can also standardize other aspects of the homebuying process that are currently cumbersome and opaque, such as title insurance.

But others feel iBuying can be detrimental to consumers. “What ends up happening is, sellers sell for less than they could have gotten, and buyers pay above market rate,” said Shaival Shah, co-founder and CEO of Ribbon, a startup that helps buyers make all-cash offers.

Some said the model is viable when home prices are rising, but given its razor-thin margins, will be tested if the market turns.

“Suppose they buy at a 3.6 percent discount and sell at a 1 percent premium,” said Tomasz Piskorski, a professor of real estate at Columbia Business School. “If housing prices drop by 5 percent, it erodes their ability to make money.”

Nima Wedlake, an investor at Thomvest Ventures, which has backed startups such as SoFi, Ladder and Lending Club, said he considered investing in several iBuyers but was deterred by their constant need for capital.

“We didn’t fully grok the model,” he said.

Mayday in March

By late March, with Covid at its height in the U.S., all of the major iBuyers suspended activities, citing massive uncertainty around pricing and fearing a housing bust. But that meant suspending a key (and, for Opendoor, only) source of revenue.

“The effect is akin to an airline losing both engines while in flight,” industry analyst Mike DelPrete wrote at the time. The pain was acute, and the repercussions swift. Within weeks, Zillow slashed expenses by 25 percent, Redfin furloughed 41 percent of agents, and Opendoor laid off 600 employees, or 35 percent of its workforce.

In retrospect, the freeze worked to iBuyers’ advantage, allowing them to avoid racking up too much inventory while nonessential businesses, including brokerages, were closed and home showings impossible. Between February and July, Opendoor reduced its inventory to $172 million worth of homes, down from over $1 billion, according to its financial statements.

Then the housing market rebounded with surprising ferocity. By May, Redfin said demand was up 17 percent compared to pre-Covid levels. July home sales surged 24.7 percent month-over-month, the largest gain since 1968, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Last month, Opendoor announced that it was going public through a merger with a blank-check company run by noted investor Chamath Palihapitiya.

“This is my next big 10x idea,” Palihapitiya, who took Virgin Galactic public in April and has invested in firms like Slack and Yammer, tweeted at the time. Opendoor declined to comment for this story, citing a quiet period before going public.

Trojan horse

iBuyers have taken pains to emphasize that they are not here to replace residential agents.

“Last year, we paid tens of millions of dollars in agent commissions,” Opendoor notes on its website. Zillow, too, has stressed that agents remain central to the homebuying process.

But last month, Zillow said it would start employing salaried agents, who would represent Zillow in its home purchases. In those transactions, Zillow Homes will be the broker of record, the company said. Atlanta, Phoenix and Tucson are first on deck with plans to expand to other cities later next year.

The move incensed agents, who spent nearly $1 billion last year advertising on Zillow.

“I’ve heard agents today saying, ‘Well, why am I buying leads from my competitor?’” said Hoby Hanna, president of Howard Hanna Real estate, a family-owned firm with $22.5 billion in sales last year according to research firm Real Trends.

Zillow tried to set the record straight. “Let me address one thing right off the bat,” Errol Samuelson, the company’s chief industry development officer, said in a video message at the time of the announcement. “We are not recruiting agents from other brokerages.”

But Wall Street liked what it saw. On the day of the announcement, Zillow’s stock price hit a record $100 per share. (It was at $105 per share as of press time.) And several analysts raised the company’s price target, suggesting they think the company’s value will go up. “The move should help Zillow improve unit economics,” Deutsche Bank’s Lloyd Walmsley wrote in a Sept. 23 note. He did not think the pivot would hurt Zillow’s lucrative Premier Agent business.

“In order to operate such a business at scale, it will be essential to drive as many costs out of the process as possible,” said Yousuf Hafuda, an analyst at Morningstar.

The full-court press on iBuying plays to what Rich Barton, who took back the CEO reins from Spencer Rascoff at Zillow last year, sees as essential to his company’s long-term prospects.

iBuying was “an existential threat because if it works and we don’t do it, we get displaced as the marketplace, theoretically,” he told the tech news website the Information last October.

Zillow’s cash cow had historically been agent advertising, but Barton said home purchases had “a mindbogglingly larger TAM [total addressable market]—$1.8 trillion of secondary market transactions happen a year in the U.S. of homes.”

That figure, however, may not be wholly relevant. In order to buy homes sight-unseen, iBuyers have strict criteria for homes they will purchase. In general, they look for cookie-cutter homes in good condition priced between $200,000 around $600,000. According to Columbia Business School’s Piskorski, the TAM for iBuyers is something like $300 billion — meaning the major players are fighting over a much smaller pot than advertised.

Piskorski also pointed to holding costs as a significant risk. “Owning an empty home is costly,” he said. Zillow declined to comment for this story.

As the two dominant players, Zillow and Opendoor are racing to add ancillary services to boost revenue, including mortgage, title and escrow services.

In a Sept. 15 investor presentation, Opendoor itemized the contribution margin, on a per-home basis, for a menu of services, including title ($1,750), home loans ($5,000) and listing your old home with an Opendoor agent ($3,750). Eventually, it plans to launch services related to home warranties, remodeling, insurance and moving, which could bring in another $7,500 per home.

DelPrete was skeptical the additions would be a silver bullet. “That’s a whopping 60 percent revenue increase from what they’re currently getting,” he said on a recent webinar. “If it was easy, it would be done already.”

And the financial strains are immense. In 2019, Opendoor lost $339 million, up 41 percent year-over-year from $240 million, it revealed during its presentation. Revenues last year hit $4.7 billion — this year, projected revenue is $2.5 billion, a drop of over $2 billion.

DelPrete noted that Opendoor had recently lowered its iBuying fee to 6 percent of the home price.

“If Zillow wants to compete, they’re going to have to lower their fees,” he said. “It’s almost like a game of chicken, profitability chicken. … Opendoor is going for it.”