Two blocks north of the portion of Hudson Yards that opened in mid-March on Manhattan’s Far West Side, another massive project is getting started. Foundation work on the Spiral, Tishman Speyer’s 65-story office tower designed by the Bjarke Ingels Group, began just last year.

And Turner Construction, one of the city’s largest general contractors, has been tapped to manage the $3.7 billion construction project, which last year secured $1.8 billion in financing from a unit of the Blackstone Group.

The 2.9 million-square-foot development, due for completion in 2022, has locked in Pfizer as its anchor tenant, and investment manager AllianceBernstein inked a 189,000-square-foot lease at the office tower last month.

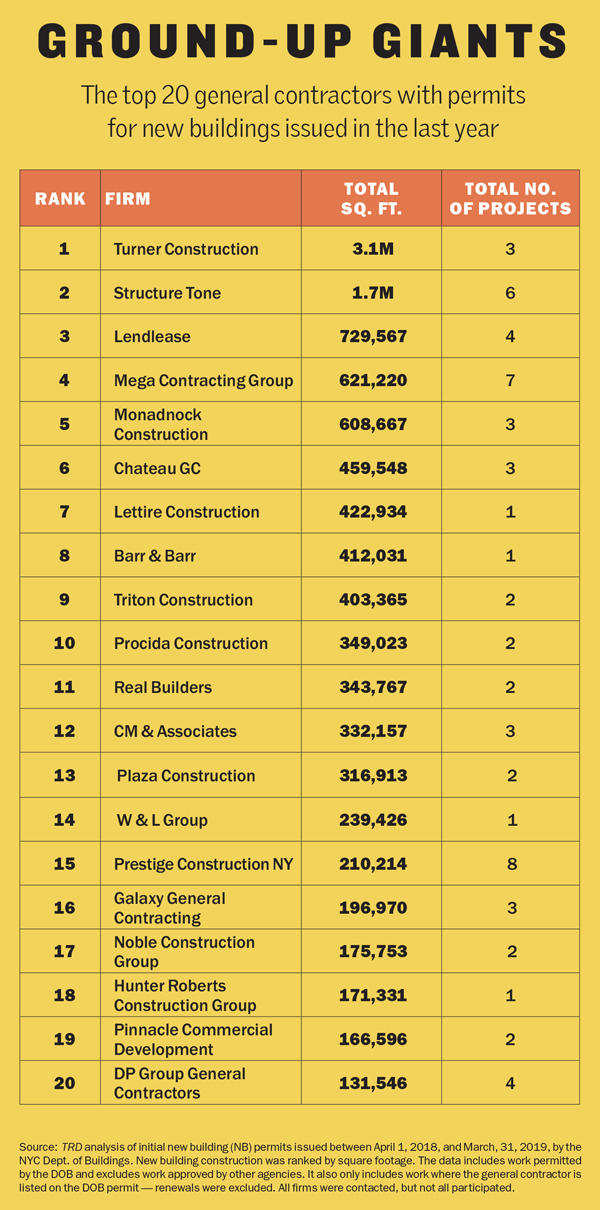

Turner had a busy past year, kicking off work on major expansions for Columbia University and Coney Island Hospital in addition to the Spiral. That diverse portfolio of new projects launched Turner into the top spot in The Real Deal’s ranking of the city’s general contractors for ground-up projects at 3.1 million square feet, up from eighth place a year ago.

But the subsidiary of German construction giant Hochtief is also dealing with several legal and compliance issues — two of its former executives were charged with fraud in December — matters that have become distressingly common in the city’s $60 billion construction industry. (Turner told TRD that prosecutors thanked the company for assisting their investigation.)

Turner and many of its competitors in the New York market are also coping with new industry pressures, from a shortage of qualified labor to foggy economic and geopolitical forecasts. Those economic pressures are forcing many general contractors to make some tough choices and explore innovative alternatives.

Against that backdrop, TRD set out this month to determine which companies grabbed the most work for new builds and renovations within the past year by reviewing hundreds of permit applications filed with the city’s Department of Buildings between April 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019.

Collectively, the top 20 ground-up builders received permits for 11 million square feet of work in the past year, down from 16.3 million in our May 2018 analysis. The top 20 firms for interior work filed plans for $3.12 billion worth of projects, a slight drop from the $3.75 billion that TRD calculated a year ago.

With the luxury residential construction boom now in the rearview mirror, other sectors — such as public investment — are emerging to pick up the slack. General contracting firms claim there is still plenty of work to go around and that they have enough staff to manage all available projects. And despite industry talk of a downturn, construction spending in the city has continued to hit new heights, according to industry sources.

“For 2018, 2019 and 2020, we’re projecting $177 billion for the three-year cycle, which will be the most in the history of New York,” said Carlo Scissura, president of the New York Building Congress trade group. He noted that while the projections for this year and next are somewhat down from 2018’s peak of $61.5 billion, each could become a potentially record-setting year in its own right.

“I think we’ve gotten spoiled. The numbers are astonishing,” added Scissura, noting that with the second phase of Hudson Yards yet to start and major projects slated for a rezoned Midtown East and the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts, his organization still has a strong outlook for the years ahead.

Boom after boom?

Turner’s rise in the ground-up construction ranks came as several of last year’s top firms — AECOM Tishman, New Line Structures & Development, Gilbane Building Company and Omnibuild — cleared their plate of new permits. TRD only examined “new starts,” not projects already in the works or that changed general contractors.

AECOM Tishman, which took the top spot on TRD’s ground-up list for the past two years but fell off it entirely this year, took issue with our methodology. The company, through a spokesperson, said that “with more than $4 billion of New York area revenue [in fiscal 2018] and 28 million square feet of construction under management” across the city, a ranking that did not put it at the top of the market was inaccurate.

Only Structure Tone, whose total square footage rose from 1.3 million to 1.7 million, remained in TRD’s top five for new builds year over year, jumping from fourth to second place thanks to its Pavarini McGovern affiliate. Newbies joining Turner and Structure Tone in the top tier of TRD’s ground-up ranks were Lendlease, which came in third at 729,567 square feet, followed by the Mega Contracting Group and Monadnock Construction, which had 621,220 and 608,667 square feet, respectively.

The new entrants broke into TRD’s top ranks after picking up permits for projects like the 300,000-square-foot Taystee Building in West Harlem (Lendlease) and affordable mixed-use buildings at 600 East 156th Street (Mega) and 1932 Bryant Avenue (Monadnock) in the Bronx.

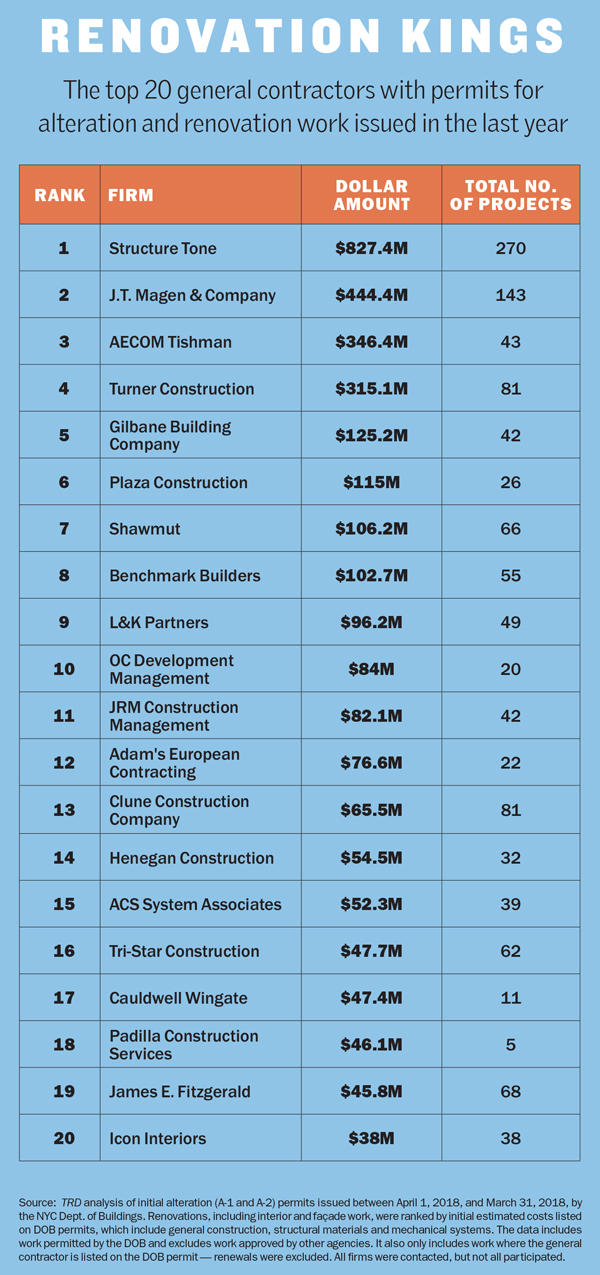

With regard to alterations and conversions, Structure Tone was top of the pile with $827.4 million in work, up from its No. 2 rank last year at $607.5 million. J.T. Magen & Company, which hit TRD’s alteration apex at $741.8 million last year, took second this year at $444.4 million. Trailing behind both companies were AECOM Tishman ($346.4 million), Turner ($315.1 million) and Gilbane ($125.2 million).

With regard to alterations and conversions, Structure Tone was top of the pile with $827.4 million in work, up from its No. 2 rank last year at $607.5 million. J.T. Magen & Company, which hit TRD’s alteration apex at $741.8 million last year, took second this year at $444.4 million. Trailing behind both companies were AECOM Tishman ($346.4 million), Turner ($315.1 million) and Gilbane ($125.2 million).

And while AECOM Tishman dropped off TRD’s new-build list, the company is still taking on plenty of new work. It broke ground in April — just outside TRD’s new-permit parameters — on the Pacific Park residential complex near Brooklyn’s Barclays Center after taking over from Turner.

Jay Badame, president of AECOM Tishman’s New York division, said office buildings, affordable housing and

airports were high on his list over the past year, while luxury condos and health care facilities remained relatively flat.

Badame, who has overseen megaprojects at SL Green’s One Vanderbilt and Silverstein Properties’ World Trade Center, added that the construction of new terminals at JFK and LaGuardia airports should be a major source of construction employment in future years. Having established relationships with subcontractors helps AECOM Tishman keep the assignments coming.

“We’ve been No. 1 [in New York] for multiple years, and clients want to go to somebody who’s not only going to start the project but has the balance sheet to complete [it],” Badame said. “Some of our competitors who are coming into the market as a new player [have to] reduce cost just to get an edge, and that’s probably short-sighted.”

Climbing costs

Construction costs in the city — and nationwide — have risen steadily since 2010. The average cost of building office space in the five boroughs is now $575 per square foot, the highest in the country, while multifamily construction costs an average of $375 per square foot, third behind San Francisco and Chicago, according to an NYBC analysis in February.

“New York City is still the most expensive U.S. city in which to build,” the trade group noted in its report. “Compared to other major cities, New York’s construction costs for Class A office and retail rank highest, and the average cost of construction ranks above all other U.S. cities.”

The cost of construction materials is subject to fluctuations in the market, which pushes those costs higher. The NYBC said that within the past year the cost of diesel fuel has risen 52 percent, lumber by 23 percent and copper piping by some 14 percent. Structural steel, whose price has been the most stable during the past decade, experienced a 9 percent price hike within the past y ear, according to the NYBC report.

“It’s very much a supply-and-demand industry, and the market is busy,” said Ralph Esposito, Lendlease’s head of East Coast construction. “And when the market is busy, contractors raise their margins. Resources are finite, so they price them accordingly.”

The federal government’s protectionist trade policies have not helped matters. In March 2018, the Trump administration imposed a roughly 25 percent tariff on steel and levied a 10 percent tariff on aluminum imported from certain countries, citing national security concerns. Steel prices climbed around 10 percent soon after that announcement, before the tariffs even went into effect on June 1 of last year. Nearly 12 months later, the city’s top construction firms are feeling some pressure from increased prices, but this has yet to result in a major operational change.

“The initial effect we felt was more on schedule than price — imports dropped off and domestic production replaced what was missing from the imports,” said Howard Rowland, president of E.W. Howell Construction Group (a Plainview, New York-based firm that did not make TRD’s rankings), noting a shift to alternative sources of steel.

Some construction companies have started to take ambiguities about potential material costs into account when signing on to new projects, said several industry players.

“Many subcontractors who use a significant amount of steel in the trades — structural steel, drywall, HVAC and electrical — have been qualifying their bids, stating prices are subject to increases in steel pricing,” said J.T. Magen President Maurice Regan.

Firms that work on larger projects often have greater exposure to such price changes.

“There’s only a few major mills and fabricators that are capable of doing the large projects that we do that range anywhere from 25,000 to 75,000 tons,” said AECOM Tishman’s Badame. “A company that’s doing 500 tons may not see that big of an impact, but when you start to look at 25,000 to 75,000 tons, a $200 per ton impact is not a rounding error.”

Badame noted that while developers are bothered by such bottlenecks, they have yet to reach the point “where people have stopped their projects.”

As is the case with many of the Trump administration’s trade policies, the future of both the steel and aluminum tariffs remain unclear. A continued lack of clarity could encourage builders to move away from steel — a staple in the city’s modern construction landscape.

“It may make some people consider doing more concrete structures than steel structures,” Badame said. “Some projects can go both ways depending on the foundation.”

Staffing shortages

Another contributor to rising construction costs has been an ever-tightening labor market. Unemployment in the U.S. construction industry hit 3.4 percent in August 2018, the lowest figure this century, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Though construction is a seasonal industry that sees a significant swing in unemployment between the summer and winter months, each yearly cycle has bottomed out a bit lower than the last this decade. Several general contracting firms told TRD that staffing levels are a primary constraint on how much work they can take on at once, with many outfits saying administrative staffers are in particularly short supply.

Though construction is a seasonal industry that sees a significant swing in unemployment between the summer and winter months, each yearly cycle has bottomed out a bit lower than the last this decade. Several general contracting firms told TRD that staffing levels are a primary constraint on how much work they can take on at once, with many outfits saying administrative staffers are in particularly short supply.

“Given the large volume of work our industry is experiencing right now, the labor shortage remains a major challenge. We’re seeing a shortage of people in all areas — including skilled workers and tradespeople, management staff and young professionals entering the construction industry,” said Structure Tone CEO Bob Mullen.

With the continued shortage of young professionals entering the industry, many construction firms are increasingly focusing their hiring practices on bringing aboard college graduates. Structure Tone’s Mullen said his firm has been able to maintain its “high volume of work” due to its successful recruitment and retention efforts.

Badame said AECOM Tishman takes a similar approach by trying to establish a relationship with prospective employees when they are still in college. “We have a great internship program here. We try to get them young and we try to get them early, so that when they’re ready to graduate they look at us as their first choice,” he said.

J.T. Magen’s Regan described a shortage of skilled and experienced project managers with precise areas of expertise.

“Our teams tend to work in specific industries on similar projects, and most of them have worked together in the past for cohesive camaraderie,” Regan said. “We look at the suitability of specific staff available when a project bid comes in. We carefully select the projects we take on so we don’t end up with more work than we can properly handle.”

Another option being explored by construction companies is recruiting from adjacent industries. Phillip Ross, a partner in the construction industry group at accounting firm Anchin, Block & Anchin, said some general contractors have branched out by hiring from architectural firms.

“There’s a bit of a learning curve involved, but since they’re still pulling in people who have been involved in construction, they tend to work out pretty well,” said Ross, although he added that the financial incentives needed to recruit people across industries can also increase costs.

Labor — and legal — woes

One major way construction firms have sought to control costs is by using nonunion labor. But that maneuver comes with its own set of challenges.

One major way construction firms have sought to control costs is by using nonunion labor. But that maneuver comes with its own set of challenges.

At Hudson Yards, where Related Companies has taken on the dual role of developer and general contractor, the past year was marked by a long-running dispute between the company and the Building and Construction Trades Council. Related accused the union group of inflating costs by $100 million and intimidating workers, as the BCTC opposed the developer’s use of nonunion labor at 50 Hudson Yards and the western portion of the megadevelopment.

In March, a week before Hudson Yards’ grand opening, the two sides came to a somewhat unexpected truce, with Related dropping its lawsuits while the BCTC agreed to stop participating in protests against the developer.

“The settlement between Related and the union is a victory for the industry,” said AECOM Tishman’s Badame, whose firm has handled vertical construction work at Hudson Yards. “It means people can pause, go back and look at where we’re aligned and where our differences are, and then come to a place that makes sense for both sides.”

The labor headaches of general contractors are perhaps only equaled by the legal troubles that some face.

In December, the district attorney’s office in Manhattan filed criminal bribery, theft and fraud charges against two top executives in Turner’s construction division and two at Bloomberg LP. The defendants and their subcontractors were indicted in a bid-rigging and bribery scheme that allegedly netted them tens of millions of dollars by overcharging for renovation work performed at two Bloomberg offices in Manhattan.

Despite that embarrassment, Turner emerged from the flurry of unwelcome press coverage relatively unscathed. The company and its CEO, Peter Davoren, were not accused of wrongdoing, and Turner spokesperson Chris McFadden told TRD that it was “not a target of the investigation, but merely a witness.”

“The [construction] starts are a good reflection on the trust clients place in Turner to achieve their goals,” McFadden said. “The former Turner employees betrayed our company, their fellow employees and our core values of honesty and integrity.”

Plaza Construction, sixth in TRD’s rankings for renovations and No. 13 for new builds, agreed to pay $9 million in restitution and penalties after being charged in 2016 over a 13-year overbilling scheme. In 2015, Tishman Construction Corporation (now part of AECOM Tishman) paid more than $20 million for a similar scheme. And Structure Tone forfeited $55 million in 2014 after pleading guilty to corruption charges filed by Manhattan prosecutors.

“Many of these companies have grown significantly over the past few years, and we’ve been working with them to make sure that their controls and their procedures keep pace with the size of the company and to make sure there aren’t any loopholes sitting inside their systems,” said Anchin’s Ross.

Some of those protocols being put in place are similar to those in industries like banking and finance, which has also seen its fair share of corruption and scandal. Ross noted that some construction firms have introduced “mandatory time away,” a common practice at big banks, which is meant to prevent employees in sensitive roles from abusing their positions.

“It’s a very complicated business with a lot of moving parts and a lot of people involved,” said Plaza Construction CEO Richard Wood. “We’re getting better and better at preventing the things you’ve read about in the past from happening again.”

One key way of managing the complexities of building projects, and reducing the opportunities for graft, is to adopt new project management technologies.

“Companies have to take the time and put in the investment for these technologies, and that puts a pressure on profitability,” said construction lawyer Barry LePatner, founder of LePatner & Associates. “You have to buy the hardware, buy the software and train people in the proper processes.”

A look forward

Though new technologies may offer another way for construction firms to mitigate risk and trim costs in the long term, the uncertainty involved in applying new methods and the upfront costs demanded by research and development have meant the industry has often been slow to innovate, sources said.

“Historically, especially in the New York market, we’ve been slow to adopt new technologies and techniques because we don’t want to retrain people,” said Plaza Construction’s Wood. “We want certainty in our projects. We don’t want this project to be the guinea pig for trying out something that may or may not provide savings.”

But as construction firms continue to invest in research and development, some previously experimental technologies are starting to become more mainstream, such as modular construction and virtual reality.

In April, Marriott International announced it would build a 26-story modular hotel in NoMad that would be the tallest modular hotel in the world when completed. And in March, the city tapped a development team led by Thorobird Companies to build a 167-unit affordable project using modular construction.

As the luxury residential market continues to cool, some construction industry sources believe that increased interest in affordable housing could provide an opening for more prefabricated and modular construction, which could allow for housing to be built faster and at less cost. Meanwhile, virtual reality is beginning to find application in some more specialized projects, such as health care facilities.

City-led initiatives may also demand a technological response from construction firms. In April, the City Council passed the Climate Mobilization Act, which requires owners of buildings larger than 25,000 square feet to cut emissions by 40 percent by 2030. That goal could cost building owners more than $4 billion in retrofit costs.

Mayor Bill de Blasio even stated that he would like to “ban the classic glass-and-steel skyscrapers” as part of the initiative. “If someone wants to build one of those things, they can take a whole lot of steps to make it energy-efficient, but we’re not going to allow what we used to see in the past,” de Blasio said on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe.”

Construction barons seem pleased with the controversial legislation.

“I think it’s a very conscientious and admirable initiative,” Lendlease’s Esposito said. “I think the challenge will be balancing world-class architecture with the desired energy efficiency. It is achievable.” Added J.T. Magen’s Regan: “The city has legislated that all construction professionals are to make sustainability one of their most important focuses.”

Still, the industry’s labor shortage could be an obstacle to the more widespread adoption of new technologies. Regan cited “productivity, project intelligence, stakeholder collaboration, costs, deadlines and client satisfaction” as spurring such advances, all of which hinge on effective recruitment.

“We adapt new technology when the benefits are clear, not just because it’s cool,” he said.