It was set to be the tallest condo tower in Lower Manhattan, capped with a ring of golden bands that arched toward the sky.

But as the new year arrived, with the high-end condo market in freefall, developers Madison Equities and Gemdale Properties pulled the plug last month on their 1,115-foot supertall at 45 Broad Street, citing “market conditions.” In the previous quarter, sales in the Financial District sank almost 45 percent.

Now, the project will be delivered later, and 80 feet shorter than expected, a spokesperson for the developers told The Real Deal — though time will tell.

“Assuming 45 Broad can’t be built as a rental, due to the costs of the project, then going on hold is a smart decision given the amount of inventory on the market,” said Andrew Gerringer, managing director of new business development at the Marketing Directors.

The site, a gaping hole encased in a cordon on a busy street in the Financial District, serves as a gloomy reminder for developers: The luxury condo boom that defined the past decade has come to an end.

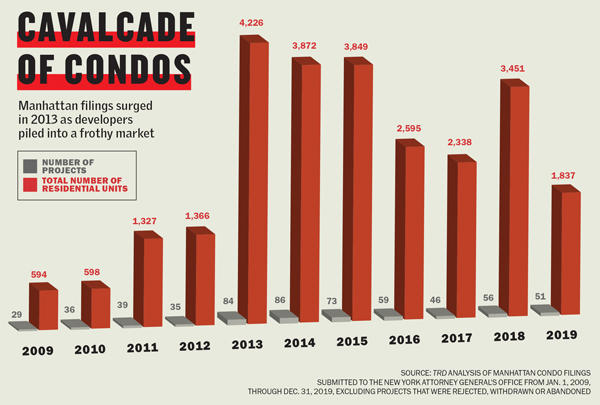

Back in 2013, when the U.S. economy was rebounding and foreign capital was flowing through the city, 84 Manhattan condo projects were filed with the New York attorney general’s office, according to a TRD analysis. The next year, that number peaked at 86.

Today, many of the units in these luxury buildings are still sitting vacant, and they could take more than six years to sell, according to appraiser Jonathan Miller of Miller Samuel.

To put that in perspective: There is $5.7 billion in existing inventory on the market and $2.2 billion in contract, according to a 2019 new development condo report from Halstead Development Marketing, which counted $13 billion in sales that have closed since 2018. Those figures combined still fall short of $33 billion worth of inventory lurking in the shadows, according to Halstead.

Condos conceived at the peak of the market are launching sales at a time defined by oversupply and uncertainty, forcing developers to cut prices, seek lender lifelines and come up with creative concessions to stay afloat. There are more than 1,000 unsold units across Manhattan’s four biggest condo projects, according to an analysis of figures from Nancy Packes Pipeline and Transactions Databases that are licensed to the real estate industry.

Related: Mondo condos — Manhattan’s four biggest projects of this cycle

“Anyone who thinks they can just sit there and charge the exorbitant prices they were able to get three or four years ago and they’re going to be able sell inventory in a prompt manner … it’s not going to happen,” said Christopher Delson, a partner at the law firm Morrison & Foerster.

While some developers are choosing to halt projects before they rise from the ground, others are opting for smaller boutique models over the gargantuan skyscrapers that hallmarked the boom. Eighty percent of the 51 Manhattan condo plans filed in 2019 were for projects with fewer than 50 units, according to TRD’s research. None of the projects had more than 200 units.

“I don’t think anyone is running to do a lot of new condo now,” said JDS Development Group’s Michael Stern, who argued the slowdown will clear the runway for new units to sell.

Others note that it’s a mixed bag for existing inventory, based on quality and price. “I think we are in a fragmented market, and all projects are not created equally.” said Robin Schneiderman, business development director for Halstead’s new development division. “While there are challenging spots, there are also spots that continue to perform very well.”

The decade’s boom-to-bust trajectory has taken a professional toll on many in the industry — and a personal one. Perhaps few have felt it more than Joseph Beninati. The Bronx-born developer burst onto the scene in 2013 with plans for a 950-foot-tall condo tower at 3 Sutton Place. But the 113-unit project collapsed under financial pressures, including costly payments on a $147 million construction loan. A 12-unit condo project at 515 West 29th Street sponsored by the developer’s firm Bauhouse Group also collapsed into litigation.

This January, Beninati filed for personal bankruptcy in Texas, disclosing that he has $24 million in liabilities and just $900 in his checking account. He surrendered the Mercedes and Audi he had been leasing. The developer, who could not be reached for comment, now earns $1,500 a month doing acquisition work for a company named Other Side Industrial, according to filings.

Beninati’s collapse was more a result of his inexperience and missteps than the market downturn. But the risk of casualty is high across the board.

“If the U.S. goes into recession, the stock market will be down, everyone will be hurting, and that will undermine the luxury market,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

“I do think recession risks, generally, are high and will remain high because of where we are in the business cycle,” he said. “The odds are probably one in five for this year, but if you told me we had a recession sometime in the next two to three years, I would not be surprised.”

A big correction?

Last March, veteran condo developer William Zeckendorf traveled to Albany to lobby against a proposed pied-à-terre tax. While his efforts helped kill the proposal, increased mansion and transfer taxes were imposed as an alternative, hitting high-end buyers directly.

These legislative changes, which followed a federal cap on state and local tax deductions, are part of a wider political shift that has rocked the industry’s long-standing power in New York and caused tension with a younger generation of activists concerned about gentrification, corporate transparency and climate change. The shift also put pressure on a sales market already struggling with a sharp decline in foreign buyers.

It’s difficult to know which factors had the most impact — from overpricing to politics to foreign buyers, the pool is vast — but by the end of the decade, no one doubted that the market had taken a major hit. In 2019, only 935 luxury contracts — which included condos, co-ops and townhouses — were signed for a total value of $7.65 billion, the lowest dollar volume since 2012, according to Olshan Realty.

As always, there were outliers: Vornado Realty Trust’s 116-unit tower at 220 Central Park South brought in record-breaking sales following its 2015 launch, including the $238 million penthouse purchased by hedge-funder Ken Griffin last January — the most expensive home sale in U.S. history.

Farther downtown, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos dropped $80 million on three units at 212 Fifth Avenue five months later, marking the largest downtown condo deal in history.

But while news of big sales gave the appearance of continued strength in the luxury market, they often spoke more to an extinct market rather than to current conditions: Many of the prices were fixed years ago when the units went into contract.

With the sales market in flux, high-end rentals reaped some of the rewards as buyers retreated to temporary homes to wait for prices to hit bottom. “Luxury rental prices boomed at the onset of the financial crisis and then stabilized for about six years, then began to climb again in 2019,” Miller said. In the last quarter of 2019, they hit a median price of $9,000 — the highest in 10 years.

Of course, in the world of big money, big stakes and big egos, real estate is an inherently risky business, and some brokers insist the narrative of doom is overstated. Volatility is par the course, they say, and New York will always be seen as an attractive place to buy.

“I think it’s easy to jump on the bandwagon and say how bad the market is,” said Douglas Elliman’s Richard Steinberg, who noted that, while 2019 was a particularly difficult year, his team saw a 50 percent increase in sales in the fourth quarter, and he was positive going into 2020.

He said the uptick showed that developers and sellers were slowly accepting that prices had to come down.

The last big drop in luxury pricing came at the onset of the financial crisis, Miller said. The current retreat is notably longer; prices peaked in 2016 and continued to fall through the end of last year. While there may be another price correction ahead, Miller said, the “heavy lifting,” by and large, is over.

Longtime Sotheby’s International agent Nikki Field said brokers themselves are jumping into the market, a vote of confidence for buyers considering their options. “My senior partner Kevin Brown bought a condo recently, and I’m buying a co-op,” she said. “When an experienced professional in the field is buying at this time, you know that we feel this is the right opportunity.”

But despite positive forecasts, the declines in recent years have undoubtedly led to collective soul searching about where things went wrong. The climate should be ideal for sales: The U.S. economy is still strong; the S&P 500 skyrocketed 30 percent last year; and interest rates are near an all-time low. Yet one-in-four new luxury condos built in New York City since 2013 were unsold as of last September, according to an analysis by StreetEasy.

The glut of inventory raises questions about whether there was ever enough demand for all the luxury units that were built and whether developers relied too heavily on all-cash foreign buyers who saw Manhattan as a safe haven for their money.

Donna Olshan, head of the boutique residential brokerage Olshan Realty, said developers should have given more thought to who was coming to the city, including the thousands of tech workers who are expected to move here in the coming years as companies, including Facebook, Google and Amazon, boost their New York operations.

“I think the developers suspend reality — if they can raise the money to build a project, they do,” she said. “They’re like Broadway producers. They always think they have a hit.”

One57 for all

When the financial crisis rocked Manhattan’s luxury condo market in 2008, everything from bank lending to construction ground to a halt. But in 2014, an ambitious skyscraper rose up over Central Park, built by Gary Barnett’s Extell Development.

One57 — a record-breaking, 75-story structure with a facade of silver and blue squares — cemented Barnett’s place as a pioneer, pushing prices higher and ushering in an ultra-competitive era of luxury real estate.

“It was the great project at the time,” said Charlie Attias, a broker at Compass who’s been selling condos in Manhattan for nearly two decades. “There was nothing else.”

But 10 years into the country’s longest economic expansion and one of the city’s most dramatic real estate cycles, Barnett — like dozens of other high-profile developers — is struggling to sell.

Extell’s One Manhattan Square, the biggest project on the market with 815 units, has sold just 223 apartments with another 39 in contract, according to TRD’s analysis of data provided by Nancy Packes.

At One57, resale prices have reflected the market’s decline. Last year retail heir David Lowy sold his three-bedroom unit at the tower for $19 million, about 32 percent less than what he paid in 2015. It was the largest resale loss of 2019.

Extell declined to comment for this story. But in an interview with this publication last December, Barnett said the city’s unpredictability has led his firm to look more outside New York and move further into rentals.

“We don’t have the velocity we’d like to see, but we are signing deals,” Barnett said of Extell’s Billionaires’ Row projects. “We are chipping away at the inventory. There’s less inventory at that super high level. There are also fewer buyers.”

He expressed confidence, however, that the Manhattan condo market would recover. For high-stakes developers, an aura of confidence can help to allay buyer nerves in a sentiment-driven climate. But some are seeing clearer results than others.

HFZ Capital’s Ziel Feldman famously paid $870 million for a full city block near the High Line — one of the priciest Manhattan land deals ever — and borrowed $1.25 billion — one of the largest construction loans of the cycle — to build his firm’s two twisting towers at 76 11th Avenue. Sales officially launched at the building in September 2018.

The developer is targeting a total sellout of $2 billion. But while New Zealand billionaire Graeme Hart reportedly went into contract for a $34 million penthouse at the building last June, there have been no recorded sales on XI’s 236 condo units to date, Packes’ data showed. HFZ declined to comment.

For now, the Related Companies appears to be leading the pack at its 15 Hudson Yards development, where 171 of the 285 units are sold, and 10 are in contract, according to the firm.

On the other end, Aby Rosen’s RFR Holding and Chinese firm Vanke have started to slash prices at its 94-unit, 63-story condo at 100 East 53rd Street, where just 23 of the property’s units had closed as of December 2019, according to public filings. The developers took on huge debt for the project, including $360 million from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

“I don’t think there’s a single new development building that has not come under pressure from banks,” Leonard Steinberg, the Compass agent directing sales, told TRD in December. “But it’s not like there’s a gun to our heads.” RFR declined to comment.

Olshan said players who are being squeezed will need to renegotiate their debt, noting that every developer has a different relationship with their backers. “Obviously, if they’re not selling, they have to placate their equity partners,” she noted.

“Some of them will stay forever and hang in there. Others won’t.”

Money matters

In Downtown Manhattan, on the border of Chinatown, Extell’s One Manhattan Square stands as a symbol of boom-era goals and market realities.

Since sales launched in 2015 — the first push targeting buyers in China, Malaysia and Singapore — the developer has introduced an array of concessions to spur deals, offering to waive common charges for up to 10 years and even launching a rent-to-own program that allows residents to try before they buy.

The program has also been rolled out at two Downtown properties owned by Ben Shaoul’s Magnum Real Estate Group.

Jordan Brill, a partner at the firm, said the plan made sense in an uncertain market fraught with psychological barriers. “Product’s moving very slow because people are being extra cautious and want to make sure they make a sound investment amidst this relative state of paralysis,” he said.

Shaun Pappas, a real estate attorney who works with Magnum, said he has been contacted by smaller developers about whether rent-to-own would work for them. One of his clients, Italian-born developer Stefano Farsura, said he was considering it for his 14-unit condo on 139 East 23rd Street. Sales launched in January, and all units are asking below $4 million. “We decided to stay flexible and see how the market reacts,” he said.

The developer, who filed plans for his project in 2019, said he had changed course as he watched the market struggle. First, he scrapped a penthouse with a rooftop garden — an “ego apartment,” he called it — in favor of making the units more uniform in price and converting the rooftop into a communal space with open-air seating and a barbeque. His next step was to push sales back to when the project was all but complete, a trend that is becoming more common because buyers don’t have the same sense of urgency they once did and often want to see their units before signing a deal.

“We have a number of condo projects that are on the drawing board — things that we know will happen — but people are holding off putting them on the market until they are close to completion, as opposed to pre-construction marketing,” said Jay Neveloff, a partner at the law firm Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel.

But as concessions, incentives and even delayed sales launches become pervasive — in many cases coupled with price cuts — the line between solid strategy and marketing gimmick can narrow. In January, star Nest Seekers broker Ryan Serhant surprised some in the industry by posing behind a pile of cash for an Instagram video, in which he announced, “I’m going to offer $50,000 in cash to the first broker who brings me a deal at 196 Orchard in 2020.” (Magnum, the firm behind the Downtown project, later confirmed it was footing the bill.)

Brill said he was surprised to see a few people suggest the promotion was unethical and put the criticism down to shortsightedness. “Any broker looking to push a transaction through today is going to offer either a piece or all of that incentive to their buyer, and what would be unethical is not sharing that extra $50,000 with their buyer,” he said.

The need to lift sales is particularly pressing for developers weighed down by large amounts of debt. One luxury condo project that almost came apart because of missed loan payments and sluggish sales is 125 Greenwich. Sponsored by Davide Bizzi’s Bizzi & Partners, Howard Lorber’s New Valley, China Cindat and the Carlton Group, the building topped out last March but is plagued by litigation and has yet to be completed.

Singapore-based United Overseas Bank, which lent $195 million on the 275-unit project, moved to foreclose on the developers at the Downtown site last summer, then sold the debt to development firm BH3 Capital Partners. A separate foreclosure action by an EB-5 lender, Nick Mastroianni’s USIF, is also stalled after a planned auction did not happen last summer. And in December, a complaint was filed against the developers for skipping seven months of rent for the project’s sales office on the 84th floor of One World Trade Center.

“If you haven’t started and gotten your construction loan yet,” the Marketing Directors’ Gerringer noted, “why would you build today in a market like this when there is so much uncertainty and so much at risk?”

Despite the challenges at some big development sites, Neveloff predicted most well-backed projects would withstand the current market pressures with plenty of options for prominent sponsors to recapitalize.

But George Doerre, vice president at M&T Bank, predicted there would be fewer construction loans in 2020.

“The number of people coming forward looking for condo financing just isn’t there,” he said, noting that rent reforms had hampered condo conversions. For those projects that were initiated, Doerre added, “you have to feel really confident in their ability to sell out.”

Tall orders

JDS Development’s Stern — one of the luxury condo market’s newcomers of the last decade — has been building an ambitious 1,428-foot development at 111 West 57th Street on the backdrop of the luxury slowdown.

The 60-unit condo project, which has a projected sellout of $1.3 billion, was co-developed by Kevin Maloney’s PMG and equity investor Ambase, which was later sidelined from the project after a drawn-out legal battle over ownership stakes and missed capital calls.

But if Stern is worried about marketing 111 West 57th — the world’s skinniest skyscraper with just one unit per floor — he doesn’t show it. After launching sales in 2016, he suspended them amid the slowdown and relaunched in 2018. While the developer declined to discuss figures, he said interest has been strong, primarily from domestic buyers. The project’s first closings are expected in April, and construction is expected to wrap this year.

His project is one of the newest on Billionaires’ Row, which has become crowded since One57 was built and is known for both record sales and disappointing resales.

A recent Miller Samuel analysis of eight buildings in the area found that close to 40 percent of units remain unsold as of September 2019. (Extell’s Central Park Tower at 217 West 57th Street was not included.)

“The developers on 57th Street started building condominiums for people that barely exist in the world,” Terra Holdings owner and co-chair Kent Swig told TRD last December. “I don’t think people did their demographic homework.”

At Vornado’s 220 Central Park South — which Miller estimated to be 85 percent sold — the 116-unit building’s golden touch is soon to be tested: The first reported resale was listed this year with owner Richard Leibovitch asking $10 million more than he paid just a year ago.

Stern said that while 2019 was difficult for the industry, the slowdown in new projects was positive.

“We should see some of the older inventory absorbed, and that bodes well for moving more product in 2020 than we did in 2019,” he argued.

Future Outlook

In the past decade, 22,304 condo units were built in Manhattan, the most of any borough, according to data from Packes first reported by The New York Times.

Although the 10 biggest Manhattan condo projects on the market have hundreds of empty units among them, Miller said condos priced below $5 million were faring well. Commentators often speak about the condo market as a monolith, he said, but sales below $5 million make up 96 percent of it. That portion, he said, “is moving sideways or rising.”

Though often discounted, sales are still happening. There were 611 condos sold last year, according to CORE’s year-end report, fueled in part by the pre-mansion-tax rush in June. That was a slight uptick from 605 the previous year but down from 840 sales in 2017 and 883 in 2016.

Many luxury brokers are still optimistic about the year ahead, while reserving caution about the potential effects of the federal election. An analysis for TRD by Jonathan Miller of co-op sales between 2008 and 2019 shows this concern is warranted: Sales in presidential election years dropped 12.7 percent between June and October and peaked again in November and December.

Global volatility, which brokers say has wreaked havoc on the sales market in the past few years, will not slow any time soon. The impeachment trial, unrest in Iran and mounting concern over climate change all play into buyer sentiment.

“The biggest concern, for me, is the pied-à-terre tax,” Elliman broker Frances Katzen said. “I think if that goes into effect — excuse my language — we’re fucked because we are heavily reliant on that investor component to diversify and absorb a big chunk of what’s being built.”

Many in the industry argue that well-priced inventory will continue to sell, though disagreement persists about what pricing is realistic. “Part of the condo story is, What is the good inventory and the bad inventory?” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Halstead Property Development Marketing. “At some point, when do we not count them as inventory anymore when they’ve been on the market for so long?”

Neveloff is confident developers can navigate the uneven terrain. “I don’t expect to see many foreclosures,” he said. “I certainly don’t expect to see many bankruptcies.”

Morrison & Foerster’s Delson differed. “My guess is we’re going to start to see foreclosures,” he said, noting that the process usually takes about two years.

Outside Manhattan, other boroughs are also showing growth, and Brooklyn has been transformed with new development in the past decade. “New York is a bifurcated market,” said Compass’ Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan. Despite industry fears of a recession, she has seen much worse.

“In the 1990s, you couldn’t give apartments away,” she said. “We aren’t in a situation like that.”

Write to Sylvia Varnham O’Regan at so@therealdeal.com