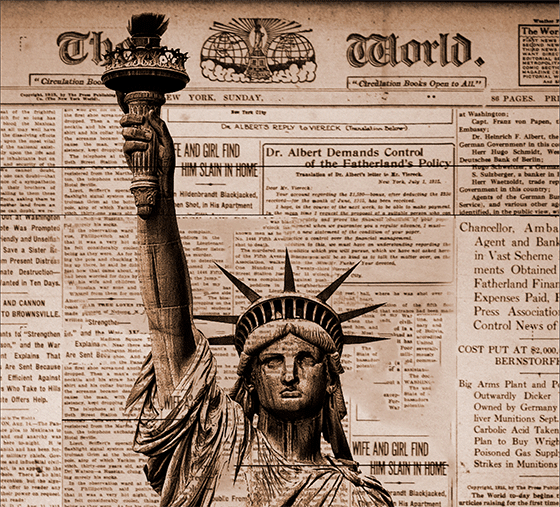

In the summer of 1885, readers of the New York World saw an unusual offering on the newspaper’s front page: its publisher, Joseph Pulitzer, asked them to donate a small sum to a “pedestal fund” that was to help finance the base of a new statue. “Let us not wait for the millionaires to give us money,” he wrote.

His appeal was successful. The campaign raised $101,091 from roughly 160,000 investors. And with that, the Statue of Liberty, whose parts had been waiting around in a New York port, was built. The iconic statue became one of the first major crowdfunded projects in the United States.

Today’s crowdfunding entrepreneurs like to see themselves as pioneers of an entirely new practice. But they are, in fact, simply reviving one that has been around for a long time.

The history of real estate crowdfunding in the U.S. offers insights into how the financial sector has changed over time.

On the most fundamental level, crowdfunding — or funding a project with the help of a large number of (usually small-time) investors — is hardly revolutionary. Developers have been funding projects through friends and acquaintances for centuries. The spread of print media and the growth of financial markets in the 19th and early 20th centuries allowed the practice to expand beyond that immediate circle of friends.

The pedestal fund was just one example of numerous offerings publicized in papers or by word of mouth that allowed investors to buy bonds or equity interests. But as the financial sector grew, so did abuses.

“A lot of bond deals and a lot of stocks came to market in what was described as a ‘self-regulated market.’ You have to keep a straight face saying that,” said Charles Geisst, an economist and financial historian at Manhattan College.

While states had their own rules, there were no overarching federal securities regulations, meaning issuers were subject to little oversight.

“There were companies that were reporting in the press that [they] were doing well when they weren’t,” Geisst said. In one case, he noted, an investment bank sold stocks to investors, assuring them the company was sound, even though it was bankrupt.

These excesses helped fuel the asset bubble that burst in 1929, plunging the U.S. into the Great Depression. In 1933, in an attempt to prevent these types of abuses, Congress passed the Securities Act.

Among other things, the law required the issuers of almost all securities to file with the newly created Securities and Exchange Commission. That turned out to be a seminal moment in the history of crowdfunding.

Filing with the SEC is expensive and time-consuming, making it all but impossible to raise small sums from investors. Still, crowdfunding was far from dead.

The age of the syndicate

On June 29, 1958, readers of the New York Times saw a 16-page editorial supplement, offering them the opportunity to buy a small stake in the leasehold of the old GM Building. The advertiser, an entity called Motors Building Realty Company, was looking to raise $5.8 million from a large number of individual investors.

But that syndication offering would likely not have seen the light of day without legendary investors Harry Helmsley and Lawrence Wien, who pioneered the practice a decade earlier.

In the late 1940s, the duo used it to build a real estate empire. The Empire State Building, which they took control of for $65 million in 1961, eventually became their crown jewel. (Wien raised $33 million from more than 3,000 investors for that deal.)

Much like crowdfunders today, Helmsley saw syndication as a way of emancipating small savers.

“The breaking up of the large sum required into small units has brought the small investor into the real estate field,” he wrote in a 1958 article in the Analysts Journal, which covers the securities industry. “Syndicates have made it possible for him to diversify his investments.”

But while syndication was crowdfunding on its most basic level, there are important distinctions from the version being used today.

For starters, the requirement to file with the SEC meant that syndication only made sense for large projects, and sums raised from each investor were sizable. A single share in the Empire State Building, for example, cost $10,000 — the equivalent of around $80,000 today.

Bringing in the crowd

As decades passed, crowdfunding advocates began to campaign for legislative reform that would make it easier to raise small sums for small projects.

The movement grew out of the fact that public and private offerings were only being shopped around to “elite investors,” said Joan MacLeod Heminway, a professor at the University of Tennessee’s law school and author of several articles on crowdfunding.

“There was nothing in it from the investor side for the John Q investor,” she said.

The lobbying effort culminated in the passage of the Jumpstart our Business Startups (JOBS) Act in 2012, which set the stage for the gradual easing of restrictions on crowdfunding.

In September 2013, Title II of the JOBS Act took effect. It allowed platforms to raise unlimited funds from accredited investors without having to register with the SEC, in effect enabling modern real estate crowdfunding. Dozens of real estate platforms have sprung up since then, offering investments in properties ranging from suburban single-family homes to Manhattan office buildings.

But so far, crowdfunding is largely restricted to accredited investors, or people with an annual individual income over $200,000, joint income over $300,000 or net wealth over $1 million. Raising money from unaccredited investors is still restricted in size, and comes with burdensome disclosure requirements.

Title III of the JOBS Act is meant to open up the market to unaccredited investors, but it is unclear when the law will go into effect.

“We’ve been waiting over three years, but still don’t know when that’s going to happen,” said Richard Swart, a research scholar at the University of California Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. For or better or worse, the century-long evolution of real estate crowdfunding is far from complete.