For decades, Staten Island development was a largely local affair.

While the borough’s population has exploded in the 50-plus years since the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge opened and connected the island to Brooklyn, most of the building has been done by small community-based developers. And those developers have mainly built suburban-style, single-family homes, especially in the southern two-thirds of the island.

The North Shore neighborhoods are more urban, but just a few projects have gone up there in recent years, and those, too, were built by small firms or Staten Island companies, as the major actors in New York City’s development community largely overlooked the city’s smallest and hardest-to-reach borough.

No longer.

Fueled by a convergence of massive retail and commercial projects now underway, including Empire Outlets and the New York Wheel, developers are transforming Staten Island’s North Shore waterfront communities with new housing.

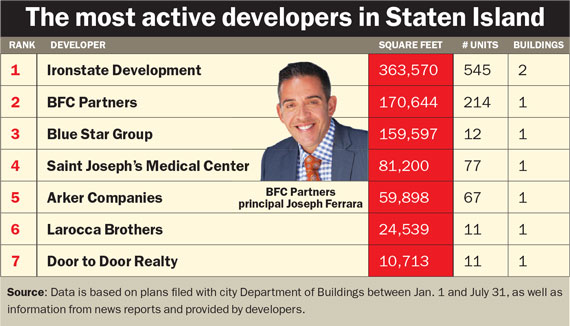

Overall, there are more than 800,000 square feet under development in Staten Island, according to The Real Deal’s analysis of building permits and offering plans filed with the city since January as well as news reports.

While that’s far less than other boroughs, it’s a significant amount for Staten Island, where current development projects are expected to add over 1,070 new residential units to the housing supply.

David Barry’s Ironstate Development, based on Hoboken, New Jersey, is leading the way, with nearly 364,000 square feet under development in a pair of rental buildings on the Stapleton waterfront permitted for a total of 545 units. The project, known as URL Staten Island, short for “Urban Ready Life,” is slated to add a third building in its second phase that will hold the balance of a total of 900 units for the complex.

Coming in at No. 2 was Brooklyn-based BFC Partners, with 170,644 square feet under development at 475 Bay Street, a planned 214-unit rental building a block from URL.

Blue Star Group, based on Staten Island, clocked in at No. 3, with a nearly 160,000-square-foot residential building at 1095 Rockland Avenue adjacent to Rockland Square, the company’s newly built townhouse development in the mid-island New Springville neighborhood.

Back on the North Shore, coming in fourth is St. Joseph’s Medical Center, a Bronx-based nonprofit that is facing community opposition for its plan to build a roughly 81,000-square-foot, 77-unit building at

108-110 Port Richmond Avenue. Residents are upset because the plans call for 50 of the units to be dedicated for mentally ill residents in a supportive housing setting.

Finally, the Queens-based Arker Companies rounded out the top five with 59,898 square feet at 533 Bay Street, a 67-unit affordable housing project for seniors.

“The motor for development is switched on,” said Jonathan Miller, president of real estate appraisal firm Miller Samuel. “At this point, it seems relatively unstoppable.”

Both public and private funds are driving the current construction efforts.

A decade ago, with practically no development taking place on the North Shore, the city authorized a redevelopment plan on the 35-acre Stapleton homeport, a decommissioned Naval base left mostly unused since 1994. Ironstate’s URL will anchor the development with its 900 residential units, 35,000 square feet of retail space and a 5,000-square-foot on-site farm. The city, with the state and Environmental Protection Fund, is also investing $130 million in public infrastructure.

Meanwhile, private investment on Staten Island is also ramping up.

“You’re seeing smart capital investing,” said Win Wharton, executive director of development of BFC, which is developing the $350 million Empire Outlets, a 350,000-square-foot retail and entertainment complex in St. George adjacent to the Staten Island Ferry terminal, with backing from Goldman Sachs.

There’s also the 630-foot New York Wheel, a $500 million project next to the outlet mall that’s been funded, in part, by Chinese investors though the EB-5 visa program.

“There’s a recognition that it’s a changing market and it might not be fully mature yet,” Wharton said. “It’s definitely behind some of the other boroughs, but you’re seeing it trending in the right way.”

Smart capital

Overall, private investment in Staten Island developments is estimated to top $1 billion in the coming years, in addition to financial backing from the city and state. Across the board, developers working on Staten Island told TRD they think the borough is overdue for a buildup.

“The waterfronts in other boroughs have already experienced development,” said Elysa Goldman, director of development at Triangle Equities of Flushing, Queens, which is building a $230 million, mixed-use development in St. George, on the other side of the ferry terminal from Empire Outlets and the Wheel.

Lighthouse Point will have 62,000 square feet of retail, a 180-key hotel and 116 rental units, 20 percent of which are slated as affordable. The project missed TRD’s cutoff, but Triangle Equities filed plans as TRD was going to press.

Triangle Equities, which landed the Lighthouse Point project via an RFP in 2007, was an early believer in the borough. “We believed in the site regardless, mainly because it’s a transit hub already,” Goldman said. “With all of these new developments happening, it will increase from there.”

Others echoed her faith in mega-projects like the outlets and the Wheel to act as a catalyst for additional development. “It doesn’t happen instantly, it’s a process,” said Ironstate’s Barry. “We want a rising tide that will float all ships,” he said. “It’s great to see legitimate developers investing heavily in Staten Island.”

Notably, outside developers are singularly focused on the North Shore, with its views, access to transportation and proximity to Manhattan.

“It’s a little bit of a tale of two cities,” said Barry, who added that throughout the rest of the island, lawmakers and activists are trying to preserve open space to alleviate traffic congestion. “It’s a North Shore, South Shore dynamic.”

Andy Gerringer, managing director of new business development at the Marketing Directors, said Staten Island is in need of rental units. “There really hasn’t been a lot of new inventory,” he said, since Staten Island is predominantly a homebuyers’ market.

The Marketing Directors is working with Ironstate to lease up its URL project, where Gerringer said apartments will come online in phases to avoid oversaturating the market. “There’s no comparable rental product there,” he said.

Compared to Manhattan, prices are a relative steal.

“You’re not going to see $900-per-foot condo sales, or $50-per-foot rentals,” said Wharton. “But you will see $30- to $35-per-foot rentals, which, quite frankly, offers an opportunity for young people and young families to live only 25 minutes from Manhattan, but get an affordable rent.”

Local developers do continue to fill in pockets with more traditional projects geared toward homeownership. Most notable is the Savo Brothers’ controversial plan to build up to 250 townhomes on the grounds of the former Mount Manresa Jesuit Retreat House, in Fort Wadsworth, about a half-mile away from the waterfront. The developer filed demolition plans last year for the retreat house buildings, which date from the late 1800s and early 1900s, and despite delays and community objection, is moving forward with the project.

Seeking affordability

Just as with other emerging neighborhoods, the North Shore has been a magnet for developers seeking affordable land prices.

BFC started its work in Staten Island with two affordable projects in Stapleton. It built 200 low-income units combined at the Rail at 40 Prospect Street, blocks from the URL site, and at 180 Broad Street, about a half-mile away.

When the city’s Economic Development Corp. issued an RFP for Empire Outlets, “we jumped on it,” Wharton said. “It’s difficult to bring something to New York that doesn’t currently exist,” he said, explaining BFC’s eagerness to build the city’s first outlet mall.

Ultimately, BFC was also able to negotiate favorable terms for a 99-year ground lease by working with the city, said Wharton.

Developers also have brought condominiums into the mix. The Marketing Directors is currently working with Meadow Partners to develop the Accolade, a 100-unit converted warehouse at 90 Bay Street, adjacent to Lighthouse Point. Plans aren’t yet filed, but prices are expected to range from $320,000 for a 720-square-foot one-bedroom to $1.35 million for a 2,300-square-foot penthouse.

Wharton said he’s encouraged by the mix of low-income and market-rate housing. “To me, that’s a true indication that it’s heading in the right direction,” Wharton said.

Bay Street corridor

Future rezoning on the North Shore would only boost the nascent development in the area. In February, the de Blasio administration targeted the Bay Street Corridor in Stapleton as one of six neighborhoods in the city that could be rezoned for residential housing, in exchange for including affordable housing units.

Already, Bay Street has attracted a cluster of development. While BFC’s project, the Rail, has an address on Prospect, the building fills a half- block on Bay Street.

Steps away from that building, Arker, which has developed more than 1,000 residential units on Staten Island in the last decade, recently broke ground on its Bay Street project.

Although that project is a ground-up construction, principal David Moritz said the firm generally acquires and renovates existing property in Staten Island because there’s limited land zoned for multi-family housing. “More than anything, land pricing is a challenge for us. Staten Island is no different than any of the other emerging areas in the city,” he said. “While it’s not $800 a foot like in Manhattan, we can only pay $30 a foot for affordable housing. So we have to be creative in the way we buy product.”

Within rising land prices, Moritz said his firm is focused more on land use now, and is buying sites with large footprints that make sense to rezone for affordable housing. “We’re priced out of as-of-right land at this point,” he said.

Ironically, despite the large-scale projects underway on the waterfront, Staten Island’s infrastructure remains lacking.

“We’re going to have real infrastructure challenges,” Borough President James Oddo said at an Urban Land Institute event in June. But, he said, “I’d rather have the infrastructure challenges that are looming than have a waterfront that is totally underutilized.”