Blackstone is handing back the keys to an outdated office building north of Times Square. In Chicago, Alliance HP walked away from the leasehold on a West Loop office. A loan on Jamison Properties’ Equitable Life Building in Los Angeles is on a watchlist of properties in danger of defaulting.

Office landlords across the nation, hammered by the work-from-home revolution, are coming to terms with the first signs of distress. While a number of buildings were struggling to make debt payments even before Covid, home offices and hybrid work schedules have accelerated their downfall. The busts may be an early sign of a larger problem concealed by slow sales activity: Many office buildings are losing value.

“I don’t think we’re ever going back to the same level of economic activity in the big cities we saw in 2019,” said Manus Clancy of Trepp, the largest commercially available database of securitized mortgages. “People have fallen in love with this three-days-in-the-office thing,” he added. “I think that’s here to stay.”

Even as masks come off and urbanites return to the cities they fled, pushing up rents, sparking bidding wars and filling nightclubs with such alacrity that Miami Beach imposed a rare spring break curfew, offices remain stubbornly lifeless. Just over 40 percent of office workers were back in buildings in 10 major cities at the end of April, according to Kastle Systems, which tracks keycard swipe data.

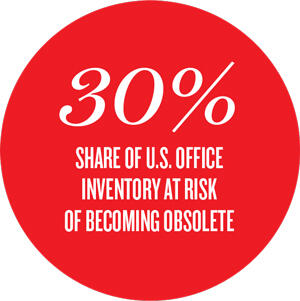

On top of that, about $1.1 trillion of office buildings — some 30 percent of the national inventory — are in danger of becoming obsolete due to changes in work patterns, according to an analysis by commercial real estate economist Randall Zisler, cited by Bloomberg.

One big caveat: Any change in building values hasn’t yet been reflected in data. Properties that have sold so far have mostly held their value. Concessions are showing signs of decreasing, and some leases in big cities appear to be recovering to pre-pandemic levels. One Vanderbilt, SL Green’s brand-new Midtown office tower, leased its uppermost office space for more than $300 a foot last month, a probable New York City record, people familiar with the deal told TRD.

Yet a recovery in sales and leasing has mostly been for higher-end assets, which are more likely to be insulated from valuation shifts. Struggling properties aren’t coming to market now and smaller tenants aren’t signing new leases, masking those changes.

“It appears that smaller-size deals are still lacking as a percentage of leasing activity,” real estate database CompStak wrote in a recent analysis. “Since smaller floor plate spaces tend to be cheaper than premier space, the recovery indicated by the average rent calculation is more of a reflection on the higher end of the market.”

Put another way, much of the market is hard to value because of a dearth of deal activity. So far, the shift is anecdotal, not based on viable data points.

“We’re still in discovery mode, and everyone is starving for more information and facts and data to really help them understand what the implied changes to value are,” said Erik Hanson of JLL’s capital markets team in San Francisco.

“We’re still in discovery mode, and everyone is starving for more information and facts and data to really help them understand what the implied changes to value are,” said Erik Hanson of JLL’s capital markets team in San Francisco.

Widespread challenges

Midtown Manhattan’s second- and third-tier office buildings faced competition from newer properties even before the pandemic. As in other markets, these properties have been the first to show distress.

At 1740 Broadway, for example, L Brands relocated to 55 Water Street in the Financial District, signing its lease in January 2020 — meaning Blackstone’s largest tenant in the 26-story Midtown building decided to move out before the pandemic.

The asset manager paid just over $600 million in 2014 to buy the now-70-year-old building from Vornado Realty Trust, which had renovated it seven years earlier.

Blackstone is reportedly handing over the property to the special servicer on its $308 million CMBS loan.

Trepp’s Clancy said the buildings that are getting into trouble are the older ones in less desirable locations that were already facing a tough road before Covid sent most office tenants home.

“Those buildings would need a fortune to be retrofitted to attract higher-paying companies,” he said.

In Chicago, a lender took control of Brookfield’s 22-story building at 175 West Jackson Boulevard in March, while the most likely outcome for AmTrust Realty’s 1.3 million–square-foot 135 South LaSalle Street is a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure, Trepp reported on March 21. The two owners had struggled to keep the properties sufficiently occupied to make loan payments before the pandemic, and were prevented from recovering as the virus raged.

New York-based AmTrust bought the South LaSalle Street property for $330 million in 2015, but longtime anchor tenant Bank of America exited its 830,000-square-foot space last year to head to its new namesake, a 57-story tower on Wacker Drive. A recent appraisal slashed the building’s value to $130 million.

“If you ever land an anchor tenant in your building, you should sell it the next day,” said Andy DeMoss, a landlord rep for Chicago-based brokerage Bradford Allen. “You’re so vulnerable to be picked off when their lease rolls.”

As occupancy declined at Jamison’s Equitable Life building in Downtown Los Angeles, the rating agency KBRA gave the 42-story Class A office tower a value of $89 million last April, when its outstanding CMBS debt sat above $92 million.

The 50-year-old building’s occupancy fell to 66 percent last June from 82 percent in late 2020, according to DBRS Morningstar, and it remains on a special servicer’s watchlist since being placed there last October. KBRA appraised the building at $150 million in 2014, when Jameson refinanced and took out $95 million in loan proceeds. The building began facing issues as early as 2018, when its largest two tenants decided to vacate.

San Francisco has probably been the slowest of the nation’s major office markets to rebound from the pandemic in terms of occupancy, said JLL’s Hanson.

About 22 percent of its office space was vacant at the end of last year, an almost fourfold increase from 2019, JLL data show. Direct asking rents, meanwhile, have decreased to about $80 a square foot a year after hitting $90 a square foot in 2019, according to JLL.

One such building downtown — steps away from Union Square, the city’s retail center — is testing the city’s office market. The 51,000-square-foot structure at 166 Geary Street consists of two levels of retail and 14 floors of offices, with the latter backing a $19 million CMBS loan that Concord Capital Partners took out from JPMorgan Chase in 2019.

Things were looking rosy for Concord, owner of the 115-year-old property’s office space, when it said in March 2019 that WeWork had signed a 10-year lease for 12,500 square feet. The deal, valued at over $10 million, made the flex-office company 166 Geary’s largest tenant and left the building more than 95 percent occupied.

Three years later, the outlook has become murkier. WeWork exited the building seven years ahead of schedule after defaulting on its lease, special servicer LNR disclosed in December. Concord began falling behind on its loan payments in April 2020 but emerged from delinquency in February after pumping more equity into the building’s offices, whose appraised value has dropped by 17 percent, to $21.5 million, since 2019, according to DBRS.

Almost 11,000 square feet of the building’s office space — the 12,700-square-foot retail condo portion of the property is owned separately by The Jackson Group — was available for lease as of April 28, according to its LoopNet listing. Concord is offering $10,000 to any tenant rep broker that gets their client to sign a full-floor lease by the end of the year, the listing said. Other San Francisco office landlords are handing out perks including higher commissions and a vacation in Cabo to avoid cutting rents in a stubbornly soft market.

Bargain buys

The data from Kastle Systems underlines the uneven pace of various office markets’ recovery.

New York- and San Francisco-area office properties tracked by the firm were 33 percent occupied in late April, trailing eight other major markets, including Chicago’s 37 percent, Los Angeles’ 39 percent and Austin’s 59 percent.

Averaged across all 10 major markets, occupancy has recovered to its pre-Omicron peak of just above 40 percent, but has generally flatlined there. Now, more than two years into the pandemic, Kastle’s index has yet to cross the 50 percent threshold.

One way to assess the impact on office building values is through capitalization rates, which aim to show how much an investor pays for a property relative to the income it generates.

While cap rates vary by market, they’ve generally stayed even or compressed slightly since the end of last year, suggesting investors haven’t yet been scared off, according to CBRE.

“In the markets that have been impacted, there’s still some uncertainty, but they’ve remained relatively stable,” said Darin Mellott, a researcher at CBRE. “A lot of this has to do with the success of the policies responding to the pandemic. Trillions of dollars in fiscal policy did a good job of maintaining asset values.”

Cap rates for trophy office buildings in Los Angeles have moved up to 4 percent from about 3.5 percent, but New York has had some compression. Mellott said secondary markets like Atlanta, Dallas and Denver have led the recovery.

Mellott noted that very few buildings have been selling. Those trading are typically well-leased properties that can attract strong pricing, so it’s difficult to assess the impact hybrid work has had on their values.

In Chicago, DeMoss said that if lenders get more aggressive in prying older properties back from struggling owners whose rent rolls were diminished by both the pandemic and the Windy City’s appetite for new development, it could propel the market upward.

“The 135 LaSalle and 175 Jackson seizures aren’t going to be the last,” he said. “There are multiple buildings that are probably in a very similar situation. If lenders take them back, that creates chances for fresh blood to come in and get it at a low basis. That’s good for the market. Some of that will flush out over a longer time horizon than we would want. I’m thinking two to three years before we’re fully out of this.”

For now, investors seem confident that markets will largely recover and that the busts will be contained, even though offices have been through a number of false starts as planned returns have been derailed by Covid spikes.

CBRE’s Mellott said a strong economy and job creation are stirring hope among investors that they will blunt the impact of companies cutting back space due to hybrid work. He said they generally say it will take three years.

“They’re clear-eyed about the changes in work patterns,” Mellot said. “The market clearly understands there are timing issues and uncertainty to be sorted through.”