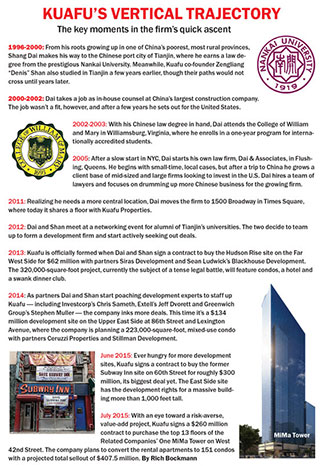

Before Kuafu Properties went on a $700 million-plus Manhattan spending spree, the Chinese development firm introduced itself last year with a routine press release.

The little-known U.S.-based company, which is headquartered in Times Square, announced plans with Siras Development to build a 47-story, mixed-use tower on the Far West Side topped off by a restaurant targeted at an international clientele, dubbed the “Shanghai Club.”

No doubt, part of the firm’s mystique — Forbes referred to it as a “mystery real estate company” — stemmed from the fact that co-founders Shang Dai and Zengliang “Denis” Shan were virtual unknowns in New York City real estate circles. In fact, the partners hadn’t even built a real estate team when they went into contract in late 2013. Kuafu was, at that time, a development company without any bona fide developers.

Since then, however, the company has turned into one of Manhattan’s most voracious and nimble buyers.

“Over the last 18 months they’ve continued to build their platform,” said Christopher Peck, a capital-markets director at the commercial brokerage HFF who helped the developers secure a $200 million acquisition loan for a pricey development site it bought this summer on the Upper East Side. The company, he added, has “diverse pockets of capital.”

The duo’s access to Chinese capital and their local connections trace back to the end of the No. 7 train in Flushing, Queens, far from the heated development grounds of Hudson Yards.

It was there, a decade earlier, that Dai founded a small law firm focused on serving Chinese clients — a business he has since parlayed into a major development firm that’s now competing for deals with some of the biggest New York City players.

While that may seem like a big leap, observers said it’s not that surprising considering the principals’ backgrounds.

Min Chan, a broker with City Connections who specializes in international development deals, said it makes sense that a successful, well-connected lawyer from China would turn his attentions to real estate.

“In China once you have the relationships — once you have the money — I think it’s not so difficult to become a developer,” she said.

Crossing paths

While they didn’t meet until years later, Kuafu’s founders both have roots that reach back to the large coastal city of Tianjin near Beijing.

It was there that Dai and Shan — who declined to be interviewed for this article — studied law and architecture, respectively, albeit it several years apart.

In 1994, Shan and two partners founded what would become China’s largest architectural firm, while Dai, after graduating law school, went to work as in-house counsel at the country’s biggest construction company.

Dai didn’t stay at the firm for long, however. In 2002, he headed to the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, to enroll in the school’s one-year masters of law program for foreign-educated students with law degrees. After graduating he made his way to New York, but it wasn’t easy going.

The economy was still recovering following the burst of the dot-com bubble, and Dai failed the bar exam his first time out, according to a Chinese-language interview he gave with Queens-based journalist Weiwei Gao in 2013 for her book “Prominent Chinese Entrepreneurs in New York.”

Dai eventually found work as a lawyer in Flushing and, in 2005, started his own firm, Dai & Associates. His timing, sources said, was spot on.

“Flushing was on the ascendancy,” said Michael Meyer, president of the neighborhood’s largest landowner, F&T Group.

“There was this parallel to what was going on in China,” noted Meyer, who joined F&T around that time specifically to go after some of the large redevelopment projects that have since reshaped Flushing. “There was the geopolitical dynamic where so much focus was on investment from Asia, particularly from China, but from Taiwan and Korea as well.”

In fact, Flushing fared better than much of the city through the post-Lehman years, and Dai’s young legal shop began to gain traction handling a wide range of cases.

According to court records, the firm took on many matrimonial cases and contract negotiations involving construction companies, trading firms and industrial outfits during those early years.

It specialized in the kind of provincial cases one would expect in a neighborhood like Flushing: wills and immigration, local developers scooping up land and residents buying homes.

Dai soon stepped away from handling the casework himself and took on a managerial role as he staffed up his business with attorneys.

Some of those initial cases included pro-bono work, such as a wrongful-death suit filed on behalf of a woman who was murdered. Her killer, a Chinese seaman in the international merchant marine, should have been deported following a conviction for a previous assault, the attorneys argued. Another case involved a woman who claimed she was defrauded by her local Buddhist temple.

In 2007, just two years after putting up his shingle, Dai opened a small office in Shanghai and began drumming up legal business there as well, he told Gao for

her book.

He tapped into a network of personal acquaintances and soon became a hot commodity in Chinese business circles: a U.S.-based attorney with knowledge and connections who could help them invest in America.

The firm started representing Chinese businesses such as the Beijing-based manufacturer Tianhai Industry Co., which makes steel cylinders for compressed gas. Dai represented Tianhai in its roughly $10 million acquisition of a company in Houston that makes valves for those cylinders.

By 2010, Dai & Associates had grown to be the largest Chinese-owned law firm in the state, with 10 employees, according to the New York Law Journal. Mainland clients accounted for 80 percent of its business.

That year was also a significant turning point for Dai’s business.

In 2010, Tianhai was charged in an anti-dumping case. In international trade, dumping is when foreign importers flood the market with artificially low-priced products in order to drive domestic competitors out of business. Several high-profile cases have involved dumping of imports from China of steel and solar-panel glass.

But instead of going with Dai & Associates, the Beijing company chose a Manhattan law firm, explaining that it didn’t feel an outer-borough outfit was up to handling such a complex litigation.

In the interview with Gao, Dai said that was when he decided to make the move to his current office in Times Square.

“You don’t see too many smaller firms like that, borough-centric firms, coming into the city in any type of large way,” said Dennis Russo, head of the real estate practice at the Midtown law firm BakerHostetler, where he works on structuring joint-venture agreements with Chinese firms. “The volume and types of deals they were doing probably started getting larger. In order to represent those kinds of clients, he probably found that he needed to be in the city.”

The ‘ultimate’ bridge

In 2011, to celebrate the firm’s new office at 1500 Broadway, Dai threw a party at the hoity Harvard Club where the guest list included an alphabet soup of Sino-American business associations.

The entrepreneur was still sticking to the legal side of real estate deals, but watching his clients and their partners closely gave him insight into a niche he could fill in the market.

“He found more and more that the Chinese people were unrealistic in how they thought they could do business here, and Americans were equally unrealistic in how they thought they could do business with the Chinese,” Stephen Muller, whom Kuafu hired as its chief investment officer, told The Real Deal in June. “Time and again, he was literally putting all the pieces of the puzzle together and making lots of money for his clients.”

By 2012 his soon-to-be partner Shan was splitting his time between China, where he was running his architectural company, and a home in Westchester, where he lived with his daughters, who came to the country to attend school. He met with Dai for the first time at a networking event for alumni who studied in Tianjin.

The two came to the realization that the combination of Shan’s success in China and Dai’s local knowledge could be a force in the real estate market, and they quickly started seeking out deals.

It was around that time that Sean Ludwick’s Blackhouse Development was on the hunt for Chinese investors to bring into a Hudson Yards deal he was eyeing along with his former partners Saif Sumaida and Ashwin Verma at Siras Development. (Ludwick has since run into serious legal troubles. In August, he was charged in the Hamptons with DWI and leaving the scene of a car accident that killed a Douglas Elliman broker. The case is still pending.)

The developers had hired a cross-cultural strategist, Zhao Jin of International Business Partners, to seek out Chinese partners. In mid-2013, Jin introduced them to Dai and Shan.

It took just a few short weeks for the Chinese pair to go into contract on the $62 million acquisition of the Hudson Rise hotel and condo development site, and by the time they closed the next year Kuafu had officially been formed.

With a Hudson Yards development site on their plate, they went to work hiring well-respected industry veterans like Chris Sameth from Investcorp, Extell Development’s Jeff Dvorett and Muller to staff up the fledgling firm.

In a May interview with TRD, Dvorett described his decision to join the company. “The future here in New York City is going to be greatly shaped by capital coming in from China,” he said. “Really the idea is to be the ultimate bridge between the capital coming in from China and us bringing sophisticated local market knowledge and development skills to putting some really unbelievable projects together.”

Kuafu — which now counts about a dozen employees — has been on a spending spree over the past two years, shelling out more than $750 million to acquire a handful of properties. The firm’s financial backing is said to come from a mix of institutional Chinese firms, high-net worth individuals and EB-5 investments.

Their acquisitions include the aforementioned Hudson Rise project, where infighting among the partners prompted Kuafu to take the extreme measure of filing to foreclose on the property in order to wrest control of it from Siras.

The unusually aggressive move prompted a countersuit from Siras, which accused its novice partners of filing frivolous litigation in an attempt to force a sale after “absorbing … Siras’s development expertise and know-how.”

“Dai, an attorney with absolutely no experience as a real estate developer, together with Shan, a foreign-trained architect with no experience in New York real estate — actively aided and abetted by Dai’s law firm — have perpetrated this scheme to misappropriate, at fire-sale prices, Siras’s interest” in the project, the developer’s attorneys wrote in the case, which is still ongoing.

Kuafu denied that and argued that its move to dissolve the partnership was not frivolous but instead the result of “irreconcilable” differences.

If that deal didn’t make the industry take notice of Kuafu, which means “beyond wealth,” its other large deals likely did.

Last December, the firm paid approximately $134 million to purchase a development site at 86th Street and Lexington Avenue, where it’s building a 223,000-square-foot mixed-use project with Ceruzzi Properties and Stillman Development International. Kuafu is seeking up to $50 million from EB-5 investors for the project.

Kuafu also paid more than $1,000 per square foot to acquire a six-property development site on East 60th Street for $300 million, where it is planning to build condos.

And, in July, news broke that Kuafu paid $260 million to buy the top 13 floors of the Related Companies’ residential project on 42nd Street, 1 MiMa tower, where the partners plan to sell 151 units for a total sellout of $407.5 million.

Speaking at TRD’s new development showcase in Shanghai this past September, Dai said that despite substantial spending over the past year and a half, the company is looking to do more risk-averse deals in what he sees to be a frothy market.

“The market right now is very hot. Land is expensive. So Kuafu right now is very careful, very cautious,” he said. “We’ve already switched our strategy from luxury condominiums to value-add projects and also cash-flow-generating projects and multi-families.”

Dai extolled the importance of Chinese and American partners working together to navigate cultural differences, as well as to choose partners wisely.

“The nature of Kuafu and the goal of the business is to build a bridge between Chinese capital [and U.S. development deals],” he said. “Are those people who have only money? Or are they people who not only have money but have knowledge and vision?