Over the first few months of 2020, real estate agents began seeing a strange new trend in their inboxes: emails advertising listings not available on a certain popular listing site.

Over the first few months of 2020, real estate agents began seeing a strange new trend in their inboxes: emails advertising listings not available on a certain popular listing site.

“NOT ON STREETEASY!” screamed the subject line of a Compass team’s e-blast about a Financial District studio going for $650,000.

“Surprise your clients as this will NOT be found on StreetEasy!” an agent from Sotheby’s International Realty wrote about a $1.5 million sales listing on the Upper East Side, and an email from a Corcoran Group broker touted a $1.2 million Boerum Hill listing with the subject line, “The best condo in Brooklyn is not on StreetEasy.”

The senders are brokers who hang their shingles with some of the biggest firms in the city, including Halstead, Brown Harris Stevens and Keller Williams New York City, and the properties are prime listings. Of 15 such emails viewed by The Real Deal touting newly listed properties being kept off StreetEasy, most were sales — with asking prices reaching as high as $5.9 million — but one of the rental was asking $13,874 per month.

Multiple brokers say they began receiving the email blasts around early February — about the same time StreetEasy stopped accepting listings feeds from brokerage firms, and a month after the listings platform hiked its daily listing fees for the third consecutive year.

It’s a far cry from the organized boycott of StreetEasy some brokers have urged in the past without success. But this apparently organic, uncoordinated shift in agent behavior may forecast an opening for a shakeup in the lucrative and competitive market of where home listings get posted and how consumers get access.

Close to 5.8 million existing homes across the U.S. were sold in February at a median price of $270,100, according to the National Association of Realtors. And who gets to take a slice of those transactions is the subject of fierce competition among major public companies that display listings, such as Zillow Group, Redfin and News Corp.’s Realtor.com, and brokerages, like Elliman’s holding company, Vector Group, or Corcoran’s parent, Realogy.

Last quarter, Zillow reported $944 million in revenues compared to Redfin’s $233 million and News Corp.’s $294 million. Elliman’s revenues came in at $784 million, while Realogy, which doesn’t break out revenue by business, reported $1.3 billion overall.

In the New York market, the 800-pound gorilla of the listings game is StreetEasy, which Zillow acquired for $50 million back in 2013.

The city’s dominant listings platform was popular with brokers at first but began sparking their ire in 2017, when it started ramping up prices, rolling out new paid advertising programs and changing the way listing data was uploaded.

While tension between the brokerage community and the site has grown over the years, rival sites have never caught hold as viable competitors. But broker resistance might finally be reaching a tipping point, providing an opening for new challengers.

While tension between the brokerage community and the site has grown over the years, rival sites have never caught hold as viable competitors. But broker resistance might finally be reaching a tipping point, providing an opening for new challengers.

StreetEasy executives declined to be interviewed for this story, but a spokesperson acknowledged the competitive landscape in a statement: “We know agents have options when it comes to posting listings, and we work hard to deliver agents the biggest audience and consumers the best experience.”

Email blasting new listings might still be a marginal phenomenon, but the volume has increased so much that Fritz Frigan, Halstead’s executive director of sales and leasing, has added a question — “Is Your Listing on StreetEasy?” — to his weekly open house index survey.

Frigan said he suspects that fed-up brokers are trying to figure out if working with StreetEasy is really worth it after all at this point.

“I think they’re testing,” Frigan said, “to see how valuable StreetEasy is in driving traffic to the listing.”

“Not on StreetEasy”

Anecdotally, at least, it appears StreetEasy might be failing that test.

“When I sent it via email, I actually got a better response being off market than when it was on the market,” said Kaptan Unugur, a Sotheby’s agent who emailed out a $2.25 million listing of a three-bedroom in Tribeca with the “Not on StreetEasy” banner.

“It creates some allure and some exclusivity,” he explained of the approach. “It’s like buying a piano signed by Elton John, and there’s only a hundred of them.”

Before the coronavirus pandemic ground the market to a halt in mid-March, Sotheby’s broker Jeremy Stein said he was receiving between two to five emails every day for listings labeled “Not on StreetEasy,” revealing cracks in the conventional wisdom that StreetEasy is the only game in town.

“That starts to make people like myself lose faith in using that search engine exclusively,” he said. “You can’t just do a search on StreetEasy and think, ‘I’m done.’”

Stein said he’s not personally shopping listings by email, and he’s continuing to put his properties on StreetEasy — at least for now.

“The reason I do is I still think, at least at this point, there are still enough consumers using it that its exposure is worthwhile,” he said. “However, I’m starting to question that.”

Stein, who is on the executive committee for the New York Residential Agent Continuum, which represents agents, said he believes that StreetEasy’s switch to 100 percent manual entry in February was “the straw that broke the camel’s back for certain people.”

Extra typing wasn’t the only thing bothering brokers about StreetEasy, of course, which has increasingly squeezed agents for revenue over the past few years

In 2017, StreetEasy rolled out Zillow’s controversial flagship revenue-generator, Premier Agent, which sells advertising that appears on the sales listings of other agents within a certain zip code. Then last year, StreetEasy launched Agent Spotlight, where agents could pay $333 to keep Premier Agents ads off their listings.

On the rental side, StreetEasy began charging daily listing fees in 2017 starting at $3 per day. In December 2018, the company hiked the fee to $4.50 per day. Then a year later, the company jacked it up to $6 a day.

In response to the coronavirus crisis rocking the industry, Zillow has announced a 50 percent discount for Premier Agent users from March 23 through “at least” April 22. But as with the virus outbreak that prompted it, that discount will presumably end at some point.

Against that backdrop, agent frustration is approaching a fever pitch, according to Heather McDonough Domi, a Compass broker and founding chairperson of NYRAC.

“StreetEasy has proven to take advantage of the agent time and again, and I think the agent is to a point where they’ve had enough,” she said. “They want to try something different.”

Streets less traveled

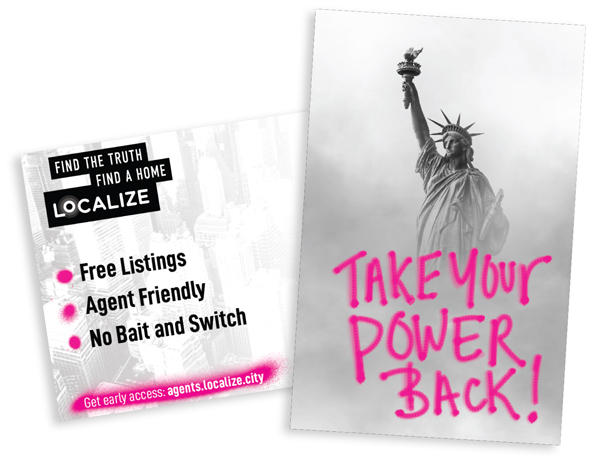

Days after StreetEasy announced a hike in rental listing fees for the third year in a row and its demand for manual entry across the board, Localize.city, a rival listings marketplace, sent out a striking mailer to brokers.

The simple postcard showed a black-and-white image of the Statue of Liberty with bright pink graffiti screaming, “Take your power back!” in the foreground. On the reverse side, Localize.city promised free listings.

“We’re proud to remind the New York real estate community that Localize.city does not charge for listings,” Localize.city president Steven Kalifowitz said in a statement at the time.

Localize.city is the U.S. subsidiary of an Israeli proptech firm that operates a similar website, dubbed Madlan, which uses artificial intelligence and a team of urban planners to provide an overview of each building’s history of violations, what’s being built or planned nearby, neighborhood crime rates, the precise hours of sunlight and level of noise.

The site launched in New York in 2018 and in the past two years has grown from an app aimed at consumers who want to know more about their apartment building into a full-fledged listings marketplace that last month launched a suite of features for agents. These include a customizable agent page and featured advertising in consumer feeds determined by search history and an agent’s expertise.

“Think of this as the best of LinkedIn for real estate,” said Andrew Kalish, Localize.city’s head of strategic partnerships. The site will charge agents a monthly subscription fee, ranging from $199 for sales and rentals to $99 for rentals only.

Matthew Hughes, a broker at Brown Harris Stevens, saw firsthand the value of a listing service that offers more information than just the address, price and whether the building has a doorman.

He recalled one client who was ready to sign on a Midtown East apartment before Hughes told them that a nightclub would be opening up two doors down, based on a permit he saw on Localize.city. That inside information nixed that deal but built client trust.

“StreetEasy was on the forefront,” he said. “[But] they don’t have any more information than I have at my fingertips.”

On-Line Residential, a firm best known for providing back-end listing management systems to brokerages, also took a shot at StreetEasy to promote its public listing portal Linecity

On January 31, the day before StreetEasy started requiring all agents to manually enter their listings, OLR sent out a letter to agents blasting StreetEasy’s data-entry demand as “a pain in the ass.”

“If you haven’t murmured ‘what a pain in the ass,’ you will shortly,” wrote OLR’s founder and president Jonathan Greenspan, going on to compare manual entry to “revisiting the stone age.”

Startup listings marketplace Localize.city sent out this mailer to brokers promising free listings last year — right after after StreetEasy announced its third hike in rental listing fees in three years.

Greenspan estimated he received 50 emails in response to his open letter.

“It was almost like Christmas morning,” he said. “You couldn’t wait to open up the next email, because people’s responses were just fabulous.”

In the weeks since then, web traffic, inquiries and demand for one-on-one meetings have all jumped, according to Greenspan, who is banking on OLR’s long-standing relationship with brokerages and agents to drive growth.

Though Greenspan said Linecity’s monetization plan has not been fully ironed out yet, he promised “fair” pricing and vowed: “I can tell you I’m never going to sell your page to another agent.”

Another listings startup aims to avoid relying on brokers for its main revenue. Kael Goodman, the founder of Marketproof, a public-facing portal that aggregates media clips, public records and listing feeds, plans on charging agents $20 per month with the bulk of revenue coming from subscriptions for developers, banks and investors.

“Everyone has their hand in the pocket of the agent, and we just don’t look at it that way. We look at agents as the water that turns the wheel,” Goodman said.

Competing with StreetEasy on price is a strategy that has been tried before, however — and by rivals far better resourced than the new crop of startups.

Back in 2017, when StreetEasy started squeezing brokers for fees, Realtor.com struck a deal with REBNY to display listings from the trade group’s industry-facing listing system. But the site was never able to gain much ground against StreetEasy among New York City consumers and brokers and even pales against Zillow nationwide, drawing only about a third as many monthly unique visitors.

Like Localize.city, Marketproof is betting on an information-rich product to lure customers and brokers with an altogether different value proposition.

Goodman said Marketproof is positioning itself as a free site with additional data and analytics available under a subscription model. One of those products is a private marketplace dedicated to listing new development inventory — including the shadow inventory being held off market. Dubbed “The Buyer’s List,” the platform is expected to launch later this year.

Rather than compete head to head with StreetEasy, Goodman said he believes creating a private marketplace around a specialized inventory and additional data analytics will be the formula to grow in the shadow of the listings giant.

“All those companies are trying to monetize an alternative to StreetEasy,” he said of his competitors. “What we’re working on here is addressing a part of the market that no one else is addressing.”

Changing its stripes

Last year, StreetEasy’s parent, Zillow Group, began moving from relying on advertising revenue to a more transaction-based model, known as Flex.

StreetEasy’s revamped Experts program now collects a 35 percent commission on any deals agents close through leads that came through the program.

Some agents were shocked at the 35 percent split StreetEasy was demanding, when the going rate for referrals within the industry ranged from 10 percent to 30 percent.

Brad Ingalls, a broker at Sotheby’s who used the Expert program “off and on” over the past four years, said last fall he would quit due to the cost.

“I’m not paying 35 percent for a referral,” he said at the time, adding that he will pay other agents a 20 to 25 percent referral fee.

Stephanie Schonholz, StreetEasy’s head of brokerage services, defended the steep fee in an interview last fall with TRD.

“Listen, we’re a business like any other business around the country,” she said. “But what I can tell you is that the cost for certain products is indicative of the value that we think they bring to the marketplace.”

Zillow’s pivot makes sense at a national level, said Steve Murray of real estate data firm REAL Trends. The first move was to “build portals, get consumer eyeballs and offer agents a way to market themselves,” but now there’s a shift into referral models.

He pointed to both Zillow’s rollout of Flex and Experts, and Realtor.com parent News Corp.’s acquisition of Opcity, which runs off a referral fee model.

Regardless of its revenue model StreetEasy is not going anywhere soon, according to experts, because of its vast consumer audience that sellers — and developers in particular — ignore at their peril.

“[There’s] nothing that comes close to StreetEasy — for the cost,” said Ilana Schwartz, who runs new-development marketing agency OMG, and whose clients include Witkoff, CIM, Brookfield Property Partners and Two Trees Management. “There’s been lots of people who try, but unfortunately the consumers are in love with StreetEasy. They have been for some time.”

Using StreetEasy’s advertising programs geared toward developers, she said she lands between one and four leads daily for projects. Even so, that doesn’t mean it’s the best option. Schwartz admitted that search and social media marketing can sometimes be more effective, depending on the type of property and price points.

“StreetEasy is the No. 1 real estate website, but not the No. 1 source of lead flow,” she said. “Google is still the No. 1 most effective way to market a property.”

Angela Ferrara of development advisory firm the Marketing Directors worked with OMG on 25 Broad Street, and she called herself a defender of StreetEasy in the same breath as she bemoaned the platform’s “unbelievable” 10 percent jump in prices for new development marketing.

The project’s developer, LCOR, is paying $26,000 for its “new development showcase” on StreetEasy and paid for a homepage featured ad for five months in 2019 at $2,900 a month — amounting to $40,500 a year.

“We spend a fortune,” Ferrara said. “I don’t know of another source that could put those numbers out there. Given that, the proof is in the pudding.”

According to Ferrara, 15 percent of the sales at 25 Broad came directly from StreetEasy, while 67 percent came from brokers, though many of them found the property through the listings giant.

Jed Wilder, a rental agent at Compass, estimates he and his team will spend the same as 25 Broad to list their rental properties on StreetEasy, if not more. Wilder pegged his annual expenses with StreetEasy’s daily $6 listing fees at between $40,000 to $50,000.

“The honest truth is that StreetEasy is where it’s at,” Wilder said, adding that it’s worth doing double entry of his listings on StreetEasy and Compass’ site.

Unugur, the Sotheby’s agent, said he does see signs of erosion of the platform’s virtual monopoly.

“You don’t see everything on there,” he said. “People have been pulling listings, like myself.”

But for now, StreetEasy still dominates the listings lane, and he will continue to rely on the site.

“I don’t necessarily support them,” he said, “but I don’t have another choice.”