The Flatiron Building, the Plaza Hotel and One Times Square are some of New York City’s most recognizable properties. The developer behind them, however, has long been forgotten.

Harry St. Francis Black, who was considered the country’s first national developer and at one point the “world’s greatest landlord,” oversaw the construction of those iconic buildings in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Black established his firm — first known as United States Realty and Construction Company and later renamed United States Realty and Improvement Company — as one of New York City’s largest developers.

And, in many ways, his brash, headline-grabbing lifestyle set the bar for the colorful players who dominate New York’s real estate industry today.

But it was not only his society hobnobbing and lavish purchases that made news. It was also his legal and personal problems.

Black was stung by martial problems, and, toward the end of his life, during Prohibition, he was accused of bootlegging liquor. Then, in 1930, at age 66, he committed suicide.

At the time of Black’s death, his estate was valued at $6 million, or roughly $89 million today, making him one of the era’s wealthiest developers.

“He was sort of this amazing figure in New York City history, and yet nobody has really heard of him,” said Alice Sparberg Alexiou, the author of “The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It,” which provides a rare account of Black, who didn’t leave behind many personal records.

“I don’t usually think developers are visionary,” Alexiou added, “but Harry Black had a vision.”

Rural roots

Black’s rise to success may have had more to do with luck and connections than education or job experience.

Born in 1863 in Coburg, a small Canadian town on Lake Ontario, Black, whose father was a major in the British Army, studied engineering. By the age of 20, Black joined a team of land surveyors in the Pacific Northwest, according to The New York Times. A subsequent decade-long gig as a traveling salesman selling woolens for a Chicago-based company was apparently lucrative enough to allow Black to establish two banks in Washington State, according to news accounts.

Harry Black

When Black returned to Chicago in the early 1890s, he courted Allon Mae Fuller, the only daughter of successful builder George A. Fuller. The couple married in 1895, and Black joined his father-in-law’s namesake firm, the George A. Fuller Company, as vice president. At the time, the company was known for its trendy steel-skeleton high-rises and was eager to expand into Manhattan.

When Fuller died in 1900, Black became the company’s president. In the following years — through a series of mergers, acquisitions and a public offering — Black amassed one of the largest construction companies in the country. He renamed the firm United States Realty and Construction Company in 1902, and the Fuller Company became a subsidiary that mostly handled construction.

Through those mergers, U.S. Realty accumulated a powerhouse roster of executives. At different times, its board of directors included railroad titan Cornelius Vanderbilt and Henry Morgenthau, then-ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. The so-called “skyscraper trust” also included Charles Schwab of Bethlehem Steel and James Speyer, a distant relative of Jerry Speyer, the current chairman of Tishman Speyer.

Black’s goal was to achieve near-total control of the New York real estate market, according to Alexiou.

And as the company grew, it gained a major competitive advantage. Because of its sheer size, Black was able to land bulk discounts for bricks, steel and other materials and parts, including elevators. That allowed him to construct buildings for 10 percent less than his rivals, according to the Times. His firm also acted as its own lender and property manager, which helped turn the operation into a well-oiled machine.

Black might have also been one of the first developers to have used syndication — or pooling money from multiple investors — to build pricey projects, such as the Plaza. On that famed property, he partnered with Bernhard Beinecke, who made his fortune in meat wholesaling, and John Gates, who got his start selling barbed wire to Texas ranchers, according to the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. The hotel cost them $12.5 million to build.

When the Plaza opened in 1907, the French château-style hotel had a stunning 1,650 chandeliers, white marble floors and bronze-and-oak revolving doors, the commission said. By most accounts, it was an instant hit. But Black didn’t live to see many gains, and in 1941, just over a decade after he died, the property was sold.

Ultimately, in a city crowded with small-time property owners, Black’s attempt to completely monopolize the market was unsuccessful.

Other builders had the same idea and were also trying their hand as real estate investors, explained Carol Willis, the founder of New York’s Skyscraper Museum.

Real estate firms like U.S. Realty’s rival Thompson-Starrett Company were just as prolific. In 1911, Black lost out to Thompson-Starrett on the chance to construct the Woolworth Building, Alexiou said.

Real estate firms like U.S. Realty’s rival Thompson-Starrett Company were just as prolific. In 1911, Black lost out to Thompson-Starrett on the chance to construct the Woolworth Building, Alexiou said.

And World War I brought skyscraper construction in the city to halt as steel was diverted to the military for ships and other war-related needs.

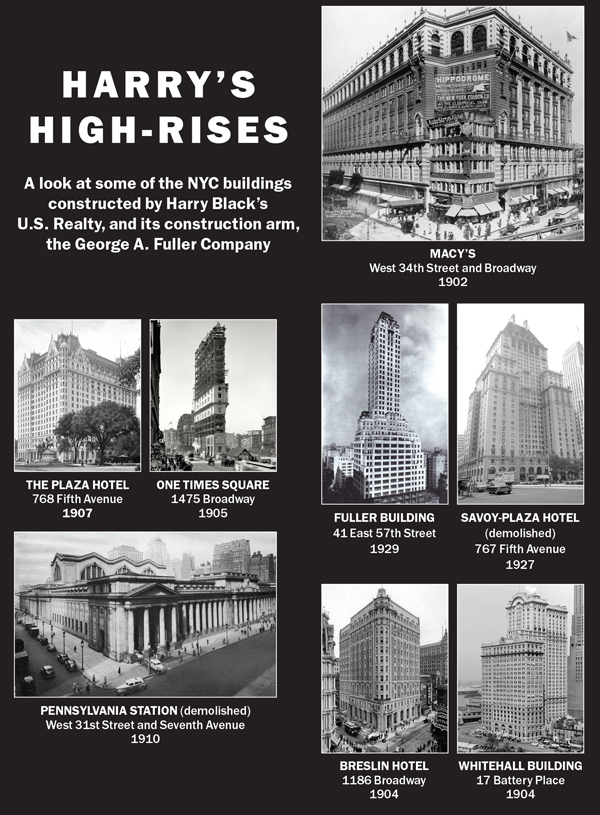

Black did, however, fulfill his father-in-law’s goal of making it big in New York. By the time Black died, the firm had built at least 35 New York City buildings, according to company records. And many of them are internationally recognized towers that still stand today. In addition, unlike its competitors, the firm was active nationwide, including Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C., as well as New York and Chicago.

Privileged but troubled

Black, who lived on Madison Avenue and later in a 23-room penthouse on the 18th floor of the Plaza, led a high-society existence — with the homes and hobbies to match.

He was a car collector and horse racer, and he had residences in Purchase, New York; Coconut Grove in Miami; and in Newport, Rhode Island, on the water.

Black also belonged to a long list of exclusives clubs, including the Larchmont Yacht Club, the Metropolitan Club and the New York Athletic Club.

The developer was so wealthy that he was able to absorb a $6 million settlement when Allon Mae divorced him in 1905 after she caught him having an affair with a nurse, a story that the press had a field day with.

Other scandals made news, too. In 1921, a year after Prohibition took effect, Black was arrested while traveling to his Florida abode by train, in his personal Pullman sleeping car, for having 55 cases of liquor, according to news reports. Another five cases were discovered on his property, but he was ultimately acquitted after testifying that he didn’t know how the alcohol got there, Alexiou wrote.

Black, who remained single for years after the divorce, eventually married Isabelle May in 1922.

But as the 1920s wore on, Black’s projects in New York slowed.

In 1925, he sold the Hippodrome, a theater on Sixth Avenue and West 43rd Street, for $6 million. That same year, he also unloaded the Breslin Hotel in NoMad, currently home to the Ace Hotel New York, for an undisclosed amount, and the Flatiron Building.

Then, in 1929, six days before the infamous stock market crash that tipped off the Great Depression, Black was found nearly drowned in a bathtub at the Plaza and had to be revived.

The following summer, on July 25, 1930, Black was discovered dead in bed in his pajamas at Allondale, a country estate in Huntington, Long Island, named for his ex-wife. He’d fired a bullet from a .38 revolver into his temple, and his valet found him about nine hours after the incident, according to the Long-Islander newspaper.

In his eight-page will, Black, who never had children, left most of his fortune to Isabelle. He also left a small portion to a nephew, George Allon Fuller, who was related to his first wife.

And he created a charity, the Harry S. Black and Allon Fuller Fund, for the “relief of unfortunate men, women and children, either sick or physically disabled,” the Times said.

Recipients of the fund, which is today administered by the Bank of America, have included the Disabilities Rights Advocates New York, Care for the Homeless and the American Civil Liberties Union. The fund had about $4.5 million in assets in 2015, according to public documents.

What happened to U.S. Realty after Black’s death is not completely publicly documented. The Westchester-based developer Cappelli Organization, which purchased the company’s assets in the late 1990s, declined to comment on the company’s recent history.

However, it appears that, like the Plaza, many of the company’s buildings were sold.

U.S. Realty seems to have been active for several decades after Black died, developing a telephone company building in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1950, for instance. A 1984 wedding announcement in the Times mentions Jack Lehman Jr., a former head of the company, and suggests U.S. Realty at that point was based in Newark.

There is also a company with the same name based in Westchester, though it could not be immediately determined if that firm is a descendant of Black’s. A person who answered the phone there last month hung up on a reporter when asked about the connection to Black.

With Black’s firm fallen into obscurity, so too has his legacy.