The sexual misconduct allegations against Richard Meier offer a telling case study for the #MeToo movement.

In many ways, the mixed messages the case sent is indicative of how the movement has unfolded in the New York City real estate industry over the last year and a half.

On the one hand, real estate firms are taking sexual harassment more seriously — not only because they’ve been forced to comply with new legislation, but also because they’re protecting themselves from financial liability. But on the other hand, cultural changes at some firms have been limited.

For Meier — who was accused by multiple former female employees and another woman of exposing himself to them and unwanted touching, among other things — there was short-term backlash. Cornell University rejected his endowment for a professorship, Sotheby’s auction house canceled a planned exhibit of his work, and GID Development quietly removed his picture from marketing materials for Waterline Square, a residential megaproject on Manhattan’s West Side where he designed one of three condo towers.

Then in October 2018, after a six-month leave of absence from his eponymous firm, it was widely reported that Meier would step down.

But that never happened. He remains a partner at the company and makes biweekly appearances in the Midtown office, though the company has set up an anonymous hot-line and made other internal changes.

“There are future generations of architects, female and male, to consider, who will be taking cues from how people let these people off easy,” said Stella Lee, one of Meier’s first accusers.

How easy remains to be seen. With this new heightened awareness about appropriate workplace behavior, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission saw sexual harassment complaints jump 12 percent in both New York and nationally from 2017 to 2018.

To get a better understanding of what changes real estate firms have made since Harvey Weinstein’s case broke open the #MeToo movement in 2017, The Real Deal reached out to more than 50 of New York City’s biggest commercial and residential brokerages and most active developers. We’ve also talked to high-ranking women since 2017 who’ve opted to stay silent about #MeToo moments, saying there’s a real risk of getting blacklisted in the industry and seeing their careers derailed.

Some firms acknowledged that the movement has prompted changes in policy. Others refused to discuss the subject, only saying that they’ve always had policies in place — or haven’t seen a need to revisit them.

“I think at all companies, including ours, collective awareness has been heightened with these stories,” said Darcy Mackay, CBRE’s chief of human resources. “It’s hard to be exempt from that.”

Legislation nation

Whether they want to or not, companies are facing a battery of new laws regarding workplace harassment and misconduct.

In January 2018, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office set up a work-related sexual violence team within its Sex Crimes Unit. The number of cases related to sexual misconduct in the workplace increased sevenfold that year across industries.

And last April, New York state passed a law requiring employers to adopt sexual harassment prevention policies as well as provide annual training to their employees.

New York City, meanwhile, extended the statute of limitations for filing cases with the Commission on Human Rights to three years from one. In January, the commission launched a unit to address sexual harassment in the private sector, and said it was investigating 180 cases of gender-based harassment in the workplace.

Although the state and city legislation both require employers of a certain size to provide annual training, the city law requires companies to train both employees and independent contractors. The latter is particularly relevant for real estate brokerages where agents operate as independent contractors and, until now, were not protected in the same way as full-on employees.

Within the world of employment law, however, there are differing views about whether the inclusion of independent contractors is an expansion of what’s already on the books.

Lawyers estimate costs for such training could range from a couple of hundred to a couple of thousand dollars for companies, though the commission offers a free training module online.

In March, REBNY issued a memo to members stating that brokerages must administer anti-sexual harassment training.

While it’s nearly impossible to get a comprehensive breakdown of what’s happening internally at private development firms, brokerages, architecture shops and construction companies, the response in the industry seems to be relatively muted.

Few firms acknowledged making operational changes beyond what they already had in place or what’s now legally required. But Mark Chin, who runs Keller Williams’ Tribeca office, said he has.

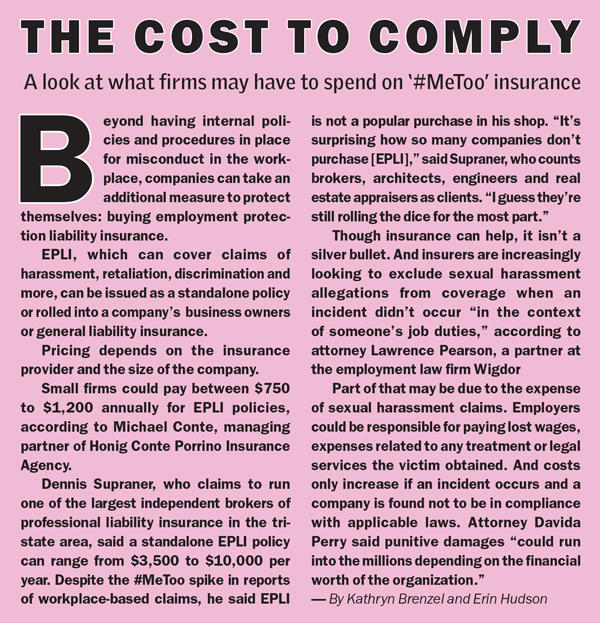

“I’m not going to lie. But we upped our insurance — our #MeToo insurance, just as a precautionary measure,” said Chin, adding that these kinds of changes have been “fairly common.”

While Chin declined to specify what kind of insurance he was referring to, lawyers said it’s likely employment protection liability insurance (EPLI) that would kick in to cover claims of harassment, retaliation, discrimination and more. And insurance brokers and lawyers say companies are, in fact, paying closer attention to it.

Under the new laws, liability extends to any misconduct a company knew about, or should have known about, and didn’t stop — regardless of whether the people involved are employees or not.

“If the UPS guy comes into your office and keeps harassing your employees and you do nothing about it, you can be held liable,” said real estate lawyer John Dolgetta of Dolgetta Law, explaining how liability has worked for years.

Andrew I. Bart, a real estate attorney at Borah Goldstein, said, however, these new laws create “very big changes.”

“A small shop can be hit with a discrimination suit just as easily as a larger developer, and they are held to the same standards of liability under these laws,” he said.

Employment attorney Davida Perry, managing partner at Schwartz Perry & Heller, said getting insurance can be crucial.

“For a smallish company, the insurance could save the company from going bankrupt as a result of having to pay a claim.”

Beyond the hard financial costs, businesses also have to face the court of public opinion.

A 2018 survey by the Washington, D.C.-based FTI Consulting warns that allegations of sexual harassment at a company — if not handled properly — will likely take a financial and reputational toll. The survey, which focused on the technology, finance, legal, energy and health care industries, found that 55 percent of professional women are less likely to apply for a job and 49 percent are less likely to buy products or stock of a company with a public #MeToo allegation.

“I think that companies need to pay attention to this, and they need to take some meaningful actions internally,” said FTI’s Elizabeth Alexander, who advises companies on crisis preparedness and gender-inclusive communications strategies. “A big thing that companies writ large across industries need to do is have clear policies and procedures for investigations when allegations arise. Everyone at all levels at the company needs to be aware.”

Outsourcing investigations

In February, Bo Dietl — the NYPD detective-turned private investigator, one-time mayoral hopeful, actor and media commentator — launched a “MeToo investigation platform” and quickly announced Douglas Elliman as one of his clients.

While he was forced to backpedal that claim when Elliman declined to publicly acknowledge whether it had hired him, Dietl said he is meeting with major developers and REITs.

Dietl isn’t an obvious figurehead for a #MeToo platform. He’s been repeatedly linked to investigations related to sexual harassment allegations against former Fox News CEO Roger Ailes. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2017 that Fox hired him to discredit two of Ailes’ accusers.

Still, he said the platform provides companies with a third-party avenue for employees to report misconduct.

“You don’t know what’s going on in a company,” he said. “It could be the most responsible, respectable person, and they could be involved in sexual harassment.”

He said the platform will help “diminish” litigation against companies, as employees can’t claim they opted against reporting incidents because they distrusted their HR departments.

Dietl’s company may be new, but law firms have been tapped to conduct these types of investigations for years.

Firms owned by parent companies with major legal and HR departments — such as Terra Holdings’ Brown Harris Stevens and Halstead or Related Companies’ CORE — are directed to take any complaints up the corporate chain of command.

Brittley Wise, COO at CORE, said any incident is immediately reported to Related’s legal team, which in turn manages all training in-house for managers and employees.

“We’re about 4,000 employees worldwide, so they have to be incredibly buttoned-up, and they are,” she said. “They dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’… They’re super conservative about following every rule.”

A representative for Meier’s architecture firm said that in addition to instituting an anonymous hotline for employees, it now has a third-party investigation firm on standby. (The company also maintains that it never said Meier would permanently step down, despite that characterization in the initial news reports.)

For some companies, the #MeToo movement is part of a broader discussion about how to ensure that employees feel emboldened to speak out when they see a workplace problem.

“The #MeToo movement just becomes a reinforcement of the messaging we’ve delivered,” said Pamela Mazza, chief human resources officer for Avison Young. “Everything we do is about the culture of the company.”

Natalie Diaz, chief of staff at development firm Time Equities, said the company has been working with nontraditional job-posting sites to ensure that more diverse candidates are aware of opportunities. Since 2017, hiring managers at the firm have been required to consider minority candidates. If the top five résumés don’t include a female candidate, the manager must bring in the highest-qualified woman for an interview, Diaz said.

“It’s easy for people to say, ‘Yeah, I would’ve loved to hire a woman for the position but none applied,’” Diaz said.

A new boogie

Those at Brown Harris Stevens know that Hall Willkie, the firm’s president, likes to dust off his dance moves at the company’s annual holiday party.

But Willkie said that in the post-#MeToo age he’s become a “more aware or cautious dancer” and will, for example, no longer grab somebody’s hand and twirl them around.

“I wouldn’t, in a dance movement, mean anything, but it doesn’t matter what my intention was — that’s the change of the mentality,” he said. “It’s not the act. It’s how the other person perceives it.”

Willkie said holding back is “kind of a shame,” but noted that his position at the company makes it a necessity.

The debate over intentions, which has Willkie on alert, is playing out on the national stage with former Vice President Joe Biden, who announced last month that he is running for president in the 2020 election. Biden is facing backlash over complaints of unwanted physical contact. While some say he’s simply an affectionate guy with good intentions, others say it’s an invasion of personal space.

More generally, the consequences of a #MeToo misstep loom large for many in the industry.

Oren Alexander, one half of Elliman’s Alexander Team, which just brokered the country’s most expensive home sale to date, said on a recent panel that what keeps him up at night is personal liability.

“What we see today is so many people have lost their business, their families, and everything due to stupid mistakes,” he said in March. “It’s so important to really make the right decisions, not just in your business but in your personal life, too. That’s something I really don’t take lightly. You gotta behave. You gotta make sure that you are doing the right thing.” Alexander declined to elaborate later on his comments.

But some think the #MeToo movement has gone too far — and hurt career prospects for women.

In some cases, sources said, men have gone into self-protection mode, opting out of mentoring female colleagues or of taking meetings with them.

Greta Guggenheim, CEO of TPG Real Estate Finance Trust, said on a panel of female REIT board members in April that “men are afraid to be alone with women.”

“I think [the movement] hurts us more than helps us,” she said.

Keller Williams’ Chin said that while he hasn’t seen that happening in real estate, he’s seen it in the broader business community.

“I’ve encountered that with people in the corporate world. They won’t even go into a meeting room alone with a woman,” he said. “They would never have dinner with a woman who isn’t their wife. They would consider that to be borderline insane behavior.”

Kirsten Sibilia, a managing principal at Manhattan-based Dattner Architects, said a contact from a construction company told her he was only scheduling working breakfasts and lunches in order to avoid dinners, where alcohol is more often consumed.

“That was kind of interesting to me. I was like, ‘Wow. Really?’” she recalled.

MaryAnne Gilmartin, who launched the development firm L&L MAG in 2018 , said she feels that the movement has overall been a positive. But the industry, she said, is still dealing with “old guard” thinking.

“It might be that the #MeToo movement makes it easier to gravitate toward a male candidate because there’s no liability associated with that candidate,” Gilmartin said. “So this question of a safe choice, which I think is absolute bullshit, but in an industry like real estate where it’s not been diverse historically, are there men who are making decisions around hires that maybe it’s concerning to hire a young woman who is vivacious and talented and capable and enthusiastic? Does that present concerns that maybe previously wouldn’t have been there? It’s possible.”

Others said avoiding one-on-one meetings is just best practice.

Halstead’s CEO, Diane Ramirez, said irrespective of gender, any kind of dinner or celebration should involve more than two people.

She said she finds that both men and women follow that practice so that “it can’t be a he-said, she-said scenario.”

But a group is not always possible. “In real estate, there’s going to be many, many times when it’s just two people in the room,” said Stribling & Associates President Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan.

She added that she always conducts employee reviews with two people and advises her agents to meet clients in the office when possible. But that attitude stems from broader safety concerns: While working in San Francisco in the early 2000s, a colleague was robbed while alone in a house with a client.

Though some, including Guggenheim, argue that “too many people are using #MeToo to settle personal grievances,” others believe the heightened attention is long overdue.

“We’ve learned how much abuse there is, or has been,” said BHS’ Willkie. “I think it’s made us all more educated.”