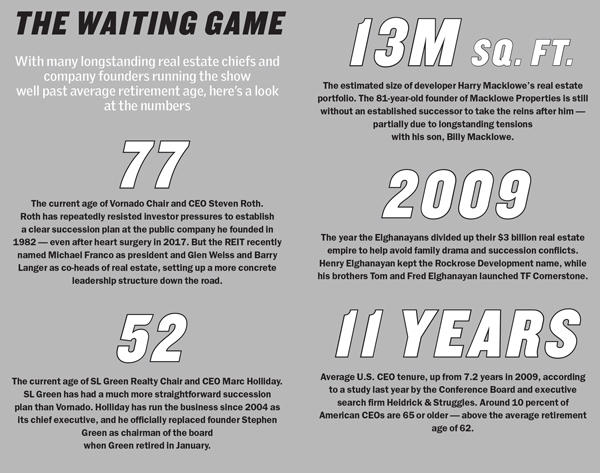

One of the main criticisms of the 2020 presidential race could apply to the New York real estate industry as well: A lot of the key players are very old.

Just as the quest to evict the 72-year-old Donald Trump from the Oval Office has been dominated by the likes of the 77-year-old Bernie Sanders, the 69-year-old Elizabeth Warren and the 76-year-old Joe Biden, the high-octane world of New York real estate is lorded over by veterans such as Vornado Realty Trust’s 77-year-old Steven Roth, Related Companies’ 79-year-old Stephen Ross, Macklowe Properties’ 81-year-old Harry Macklowe and Silverstein Properties’ 88-year-old Larry Silverstein.

And unlike the presidency, which has a succession plan enshrined in the Constitution, real estate firms don’t always have a clear idea of what they’ll do if an iconic founder or executive’s reign comes to an abrupt end. There have been some prominent cautionary tales in the recent past, such as Ceruzzi Properties and Fisher Brothers. A lack of succession planning can spook banks, employees, partners and the market.

“Very often, what you’ll have is an individual that is closely identified with the business — almost the business’s alter ego —and that can be enormously beneficial to the company,” said Morris DeFeo, co-chair of the corporate department at Herrick Feinstein. “But it can also create some potential challenges to the company, particularly if there is no clear plan of succession.”

Unlike other major industries such as Wall Street, where shareholder pressure, influential boards and intense media scrutiny have forced firms to take succession planning seriously, real estate continues to operate on the Great Man theory: Founders have almost complete control over their companies, and their substantial egos often prevent them from designating an heir apparent. Why bother worrying about who comes after you when you expect to live forever?

This devil-may-care attitude can persist even after a major event. In August 2017, Vornado’s Roth suffered a heart problem while golfing in the Hamptons, underwent double-bypass surgery and spent the better part of the month on medical leave. But the REIT still failed to reassure the market by designating a successor.

There are signs of change, however. As real estate becomes more institutionalized, as more B-school types fill the ranks and as more money flows in from private equity and pension funds, leaders are being compelled to get with the program. Related was one of the first big firms to embrace this new reality, with Ross designating Jeff Blau, now 51, as his heir in 2012. And this January, Gary Barnett, at a relatively sprightly 63, tapped Westbrook Partners’ Sush Torgalkar, who is in his early 40s, to be the CEO of his company Extell Development.

There are signs of change, however. As real estate becomes more institutionalized, as more B-school types fill the ranks and as more money flows in from private equity and pension funds, leaders are being compelled to get with the program. Related was one of the first big firms to embrace this new reality, with Ross designating Jeff Blau, now 51, as his heir in 2012. And this January, Gary Barnett, at a relatively sprightly 63, tapped Westbrook Partners’ Sush Torgalkar, who is in his early 40s, to be the CEO of his company Extell Development.

Succession planning consultants are beginning to infiltrate the industry, aided by attorneys who help massage the bruised egos and navigate the thorny dynamics that may arise. But even bosses who get that their firms need to keep going without them have an easier time planning for it in theory than in practice, according to Luzita Kennedy, managing partner at the succession advisory firm Pulvermacher Kennedy & Associates.

“When the patriarchs start to prepare for succession planning, I’d say intellectually they get it,” Kennedy said. “But when they start to actually go through it, there is a transition period because they have a really tough time letting go.”

Public domain

Warren Buffett’s investment playbook is closely followed by millions of speculators worldwide. But when it came to the future of his own Berkshire Hathaway, the “Oracle of Omaha” stayed silent for years. Finally, in January 2018, Buffett, 88, elevated two longtime executives to the role of vice chairs, describing the decision as “a movement toward succession over time.”

Buffett’s announcement calmed a lot of jittery nerves in the investment community, and with good reason. Many issues can arise if succession planning is poorly handled. Top talent may view the passing of a founder as the moment to leave, and competitors may see it as a good time to shore up their ranks. If no real plan is in place, the company’s remaining stakeholders may just decide to sell the firm or its assets off — usually at a discount.

“People are going to sense the desperation there,” said Barbara Lawrence, also of Herrick. “And it’s going to affect the price.”

Roth is a notorious example of a real estate executive ruling the roost with a succession plan that can generously be described as muddled. Michael Fascitelli, Roth’s protégé and former Vornado CEO, was for years seen as the future of the firm. But in 2013, Fascitelli, 55 at the time and one of the few industry figures with a personality as colorful as his mentor’s, announced he was stepping down from his position and taking a break from “working like a dog.” He went on to found his own investment firm, and Roth spent the next few years running the business without a hint of who would follow him. In his annual letter to investors in April 2018, months after the heart surgery, Roth wrote that he felt “fine” and planned to continue running the company.

Roth is a notorious example of a real estate executive ruling the roost with a succession plan that can generously be described as muddled. Michael Fascitelli, Roth’s protégé and former Vornado CEO, was for years seen as the future of the firm. But in 2013, Fascitelli, 55 at the time and one of the few industry figures with a personality as colorful as his mentor’s, announced he was stepping down from his position and taking a break from “working like a dog.” He went on to found his own investment firm, and Roth spent the next few years running the business without a hint of who would follow him. In his annual letter to investors in April 2018, months after the heart surgery, Roth wrote that he felt “fine” and planned to continue running the company.

But even he has since taken steps to acknowledge his mortality.

This April, Vornado promoted Michael Franco to president, and Glen Weiss and Barry Langer became co-heads of real estate. Former president David Greenbaum stepped back from the firm and took on the title of vice chair. And Haim Chera, the 50-year-old scion of the Chera retail dynasty, came aboard to head up the REIT’s retail operations.

“We’re having fun, sort of, [with] the transition of bringing the young bucks up and the old guys sort of packing up,” Roth said on Vornado’s earnings call in April.

These moves are as close as Vornado will get to a succession plan, according to Alex Goldfarb, a senior analyst at Sandler O’Neill & Partners. The lack of one, he said, had long irked investors, but Roth has generally snubbed such concerns.

“I don’t know that he’ll ever admit that there’s pressure from shareholders,” Goldfarb said. “I think he just reached the decision on his own that it was the right time, because really, people have been pressuring him for years, and he’s resisted the pressure for years.”

Vornado did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Succession at two other major New York-focused REITs has been more straightforward. Marc Holliday, 52, has been running the show at SL Green Realty for years as CEO. Last spring, company founder Stephen L. Green announced that Holliday would also replace him as chair. And at Boston Properties, co-founder Mort Zuckerman stepped down as CEO in 2013 in favor of the firm’s current CEO, Owen Thomas.

Thomas, 57, was seen as a surprise choice, with most people assuming company president Doug Linde — the 55-year-old son of Zuckerman’s co-founder and friend Ed Linde — would take over. After the pick was made public, Zuckerman told The Real Deal that he liked Thomas’ “easygoing style” and that the firm “did not do this casually.”

It was intimidating to follow in Zuckerman’s footsteps, Thomas acknowledged in an interview. But the stability helped.

“The president, the CFO and all the regional heads, they’ve all more or less stayed in place since I’ve been here,” he said, “and I think that’s been extremely important to the effective transition that we’ve had.”

Goldfarb echoed this point, saying it allowed Thomas to succeed despite his outsider status. If he had tried to mold the firm completely in his own image, it would have been a different story.

“He didn’t make it his company,” Goldfarb said. “He recognized that there was a tremendous amount of loyalty to Doug and that the company was a combination of all these different important people.”

In some cases, real estate’s growing stature and importance in the broader financial world can impact succession.

In February 2018, Jonathan Gray, widely seen as the architect of Blackstone Group’s real estate strategy — a playbook that saw the division leapfrog private equity as the firm’s biggest business — was named president of the company, cementing the 49-year-old’s status as heir apparent to 72-year-old founder Steve Schwarzman. Gray’s division, which now has over $115 billion of assets under management, was entrusted to Kathleen McCarthy and Kenneth Caplan.

“This succession was a very smooth transition,” McCarthy said at a recent panel discussion in Hong Kong, “because we’re running the business now the same way we’d really been running it for a long time.”

McCarthy’s promotion marked a still-rare instance of women moving to the top of the male-dominated real estate industry. Moves like that could also usher in a shift in the industry’s broader corporate culture — it’s hard, for instance, to imagine the next generation of leaders pulling a Sam Zell.

At an investor conference last year, Zell, the 77-year-old chair of Equity Group Investments, responded to a question about promoting women at his firm by saying: “I don’t think there’s ever been a ‘We gotta get more pussy on the block, OK?’” (After his comments provoked outrage, he apologized.)

Boards are often slow to tackle the problem of a CEO who’s behaving in a way that can hurt the company, said Gerry Pulvermacher, a partner at Pulvermacher Kennedy, because they assume the CEO is irreplaceable.

“In the long run, these organizations start to suffer for a variety of reasons when they allow this kind of behavior to go on,” he said, “whether it’s racial discrimination or gender.”

Famjam

At family-run real estate companies, succession planning has generally followed the same mantra: unto the sons.

“I have children,” said Jerry Wolkoff, the 82-year-old patriarch of G&M Realty, whose projects include the controversial 5Pointz development in Long Island City and Heartland Town Square in Suffolk County. “I’ve got my sons, David and Adam, and my grandchildren that are not old enough, but that’s our succession plan: family.”

Wolkoff believes that older executives at the top are still delivering, because the industry is too cutthroat to be sentimental.

“They’re doing a competent job, generally speaking,” he said. “Otherwise, why would they keep them?”

“The only thing that takes you away,” he continued, “is illness.”

At Clipper Equity, David Bistricer sees himself passing the mantle on to his son Jacob, who’s been at the firm for over a decade and is currently COO. But as for a timeline, there isn’t one yet.

“I’d like to say they’d need five people to replace me,” Bistricer, 69, said, “but I don’t want to be so presumptuous.”

And at Tishman Speyer, Jerry’s Speyer’s son Rob, a former reporter at the New York Daily News, was named co-CEO in 2007. Both Speyers have veto power over every major decision the firm, one of the world’s biggest developers, makes. When the company was in the final stages of negotiations to redevelop Hudson Yards, for instance, Rob and Jerry made a late-night stop at the Upper East Side diner Three Guys, according to Charles Bagli’s book “Other People’s Money.” There, over tuna sandwiches, Jerry told his son: “You’re going to be living with this project a lot longer than I. It needs to be your decision.”

And at Tishman Speyer, Jerry’s Speyer’s son Rob, a former reporter at the New York Daily News, was named co-CEO in 2007. Both Speyers have veto power over every major decision the firm, one of the world’s biggest developers, makes. When the company was in the final stages of negotiations to redevelop Hudson Yards, for instance, Rob and Jerry made a late-night stop at the Upper East Side diner Three Guys, according to Charles Bagli’s book “Other People’s Money.” There, over tuna sandwiches, Jerry told his son: “You’re going to be living with this project a lot longer than I. It needs to be your decision.”

“We’re not doing it,” Rob replied.

Tragedy or bitter conflict can unravel even the best-laid plans.

Fisher Brothers, for instance, had to cope first with the death of 52-year-old Anthony Fisher in a plane crash in 2003 and then with his 65-year-old brother Richard Fisher dying of cancer three years later.

The firm declined to comment for this story. But in a 2016 interview with TRD, company partner Kenneth Fisher said that you “don’t come back from something like that.” However, he characterized the firm’s response to the tragedies as simple.

“Just keep the ship sailing straight,” he said, “and wait for some more Fishers to get in.”

And at Macklowe Properties, after years of being groomed by his father, Harry Macklowe, to take over the firm, Billy Macklowe struck out on his own in 2010. In 2016, the problems between the two grew broader, with Harry slapping his son with a $300 million lawsuit over an operational dispute. Billy stood by his mother, Linda Macklowe, during her acrimonious split with Harry in 2017. As it stands, Harry does not have a successor to take over a real estate portfolio estimated to span about 13 million square feet. Harry did not respond to requests for comment, and Billy declined to comment.

The drama flared up anew this past March, when the 81-year-old Harry, who the New York Post dubbed a “lusty, long-in-the-tooth Lothario,” put up a 42-foot-tall billboard of his new wife on the side of his supertall 432 Park Avenue.

The drama flared up anew this past March, when the 81-year-old Harry, who the New York Post dubbed a “lusty, long-in-the-tooth Lothario,” put up a 42-foot-tall billboard of his new wife on the side of his supertall 432 Park Avenue.

Hard choices

Some firms, grappling with multiple possible successors, have had to make tough calls.

In 2009, the Elghanayans, one of the most prominent dynasties in the business, split up their $3 billion property empire. Brothers Tom and Fred Elghanayan started a new firm, TF Cornerstone, while their elder brother Henry Elghanayan held on to the Rockrose Development name. His son Justin is now president of Rockrose.

Henry initiated the split starting in 2008 in the hopes of avoiding infighting among the next generation. The brothers did not tell their parents about the split to avoid upsetting them.

TF Cornerstone did not respond to requests for comment, while Rockrose declined to comment. But one source familiar with both firms said the family’s decision was unusual given how forward-thinking it was. The brothers wanted to formalize a divide before someone got seriously sick or too many tensions arose. Most family firms shy away from contemplating those possibilities.

“It’s a psychological tendency to not want to think about the downside,” the source said. “It’s like a prenuptial. It’s not fun to think that things could ever not be perfect.”

Pulvermacher recalled advising a real estate family with several sons that wanted to expand their company. The firm ultimately determined that the youngest brother was best qualified to lead the push, but that did not sit well with his siblings.

“One of the brothers really had his nose out of joint because both he and his spouse were convinced he was the right guy for the job,” Pulvermacher said. “He was really good, but not for what they were thinking about doing, so it caused a great deal of strife in the organization.”

“One of the brothers really had his nose out of joint because both he and his spouse were convinced he was the right guy for the job,” Pulvermacher said. “He was really good, but not for what they were thinking about doing, so it caused a great deal of strife in the organization.”

Minimizing sibling rivalry — or at least making it seem less personal — is one of the main services that succession planning firms provide. Even in situations where the founder knows which family member is best suited for the top job, enlisting an outsider to ratify the decision can help other family members accept it.

“At times, the patriarch knows which family members need to be in what positions,” Kennedy said. “But because they want to avoid any conflict or any contention, they will use people like us to be an honest broker.”

This divide between what’s best for the business and what’s best for the family is one of the trickiest things for executives to navigate, according to Herrick’s Lawrence. The person they want to inherit their wealth is often different from the one they want to shepherd that wealth, she said.

“It’s almost like their business is another child to them,” she said, “in the sense of having hopes and aspirations for their business. And a lot of times, that is very different from what is economically or relationship-wise best for their family members.”

One of the city’s most prolific residential developers ended up looking past family when charting the future of his firm.

In January, Extell’s Barnett tapped Torgalkar, then the COO of Westbrook Partners, to be the CEO of his development firm. Though they’re often spotted together at industry events, Barnett is still very much the driving force at Extell and has not stepped back one bit, sources said.

“I just sold the last unit at the Carlton House, and Gary was the one that did the negotiation with me directly,” said Douglas Elliman’s Tamir Shemesh. “He’s extremely involved and knows every detail of everything.”

Sources said abdicating the throne was never in the cards for Barnett. But given the company’s size and its volume of active projects — it listed units for the city’s priciest condo project, Central Park Tower, last month — he was said to be mulling over the idea of bringing on a CEO for several years.

Sources said promoting an internal candidate (even Dov Hertz, former head of acquisitions, who left in 2016 to form DH Property Holdings) never really made sense given Extell’s relatively siloed approach to management.

“There’s not really a C-suite. Gary really is the driving force and the vision and the execution,” said one source, who said Barnett knew he needed more of a “generalist” to help him run the company. “At some stage, you’re so big that it doesn’t work to be all the things unless there’s someone to help do that.”

Torgalkar is seen as someone who can help formalize the company’s decision-making process, raise institutional money and tap global connections to help Extell grow. As for succession, several of Barnett’s family members work for him, but there’s been little in terms of grooming them to take charge.

“Do I see Gary ever giving the keys to the castle to somebody else? No, I don’t,” one source close to the company said. “I mean, everybody dies at some point, but I don’t see Gary retiring.”

Of house and home

Residential firms have also been grappling with the issue of succession.

When Elliman tapped Scott Durkin, now 57, to be president in December 2017, the move generated intense controversy at the brokerage, New York’s largest. Steven James, the CEO of Elliman’s New York division, was said to feel humiliated about being overlooked in favor of a relative outsider and considered leaving the company. He stayed on only after Howard Lorber, chairman of the firm and its largest shareholder, assured James that he’d continue reporting directly to him.

And while Lorber, 70, aggressively denied that CEO Dottie Herman was going to leave after Durkin’s promotion, by the end of 2018, Herman had sold her stake in Elliman for $40 million to Lorber’s Vector Group. Though Herman, 66, remains CEO, many have described her role as being largely that of a brand ambassador.

At Warburg Realty, Clelia Peters, 41, joined her father, Frederick Peters, 67, in 2014. And at Stribling & Associates, Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan, 40, joined her mother, Elizabeth “Libba” Stribling, 74, at her eponymous firm in 2003.

Neither woman, however, became boss right away.

Peters initially took an advisory role before becoming president in 2016. And Stribling-Kivlan — who worked at a San Francisco-based brokerage after college — started as an agent at the firm.

“If I hadn’t worked somewhere else, I don’t think Libba would have taken me,” she said. “My mother gave me one deal — a $250,000 buyer in Brooklyn. I grew my own business. I hustled to do it.”

Stribling-Kivlan’s portfolio grew through the years, and she became president in 2013. For six years, mother and daughter ran the 300-agent firm together. But in April, they decided to sell it to Compass, a move that Stribling-Kivlan said gives the firm the best odds to thrive at a time when residential brokerage is besieged by competition from online aggregators, listing platforms and lower-fee startups.

“We would never do anything without us both being fully on board,” she said. “I stand by our decision and think it’s the best decision we made.”