Even after William Zeckendorf Jr. had been firmly established as a major developer in his own right, building neighborhood-altering mega-projects from the Upper West Side to Union Square, he maintained a profile so low that it sometimes seemed an intentional rebuke to that of his larger-than-life father, William Zeckendorf Sr. [TRDataCustom]

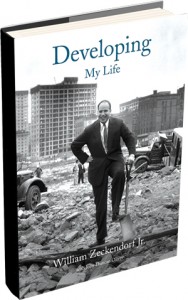

It seems only fitting, then, that Jr.’s autobiography, “Developing: My Life,” published by Andrea Monfried Editions last month, would appear quietly and posthumously, with a half-apology at the start. “For years I put off writing about my life in development. I’m pretty private, and I’d rather do something than talk about it,” Zeckendorf Jr., who died in 2014 at age 84, demurs. But family, including his sons, Arthur and William, who developed 15 Central Park West and a number of other ultra-luxurious towers, finally prevailed upon their father to turn out this 300-page volume, which was written in collaboration with Joan Duncan Oliver.

By contrast, Sr. — the consummate showman responsible for developing the United Nations site — seemed to have a colorful story about everything, including how he came to write “Zeckendorf: The autobiography of the man who played a real-life game of Monopoly and won the largest real estate empire in history.” The first real estate deal that he put together after going bankrupt in the 1960s was extending the lease of a publishing house. In exchange, they demanded his memoirs.

But while Zeckendorf Jr. may lack his father’s flair, he was a historic heavyweight — in 1986, the New York Times named him the city’s “most active real estate developer,” citing the 20 developments worth well over $1 billion that he was a partner in — and his autobiography is well worth the read. While I suspect the larger world will take little note of the book, for those of us who have an avid interest in real estate, especially Manhattan real estate, this volume is catnip.

It possesses an unintentionally charming candor, a complete lack of guile or posturing that is both welcome and informative.

All the same, almost every chapter in this book progresses with methodical detail, offering a systematic review of each of the developer’s 27 main ground-up developments in Manhattan, along with one in Queens. Along the way, Zeckendorf self-deprecatingly writes about dropping out of two universities, his military posting in Korea, his long and happy marriage to his second wife, Nancy, and the rise and fall of his father. But he invariably and dutifully returns to the task at hand: explaining to non-developers the particulars of what a developer does.

Or, I should say, a developer like Zeckendorf Jr., who operated on an entirely different level than the many unimaginative garden-variety developers that people tend to conjure up in their mind’s eye when they hear the term — those who simply buy land, build on it and sell the resultant structure. Most people have no idea of the larger vision that informs a man like Zeckendorf Jr., the ability to imagine how a run-down parking lot could be so much more.

Furthermore, most readers will be unaware of the almost unearthly patience the developer needs, harboring an ambition for decades in some cases before ground is broken. Likewise, few will have any inkling of the song and dance needed to stitch together a lot from a number of smaller lots with discordant and recalcitrant owners, or the politics of enticing investors and navigating the labyrinthine corridors of city hall.

The average city dweller is apt to pass through the streets of the metropolis every day of his life without once pausing to wonder how a specific building came to inhabit a specific lot. Providing answers to such questions and prying open the mind of the reader is the great service and invaluable gift of this largely unassuming autobiography.

The average city dweller is apt to pass through the streets of the metropolis every day of his life without once pausing to wonder how a specific building came to inhabit a specific lot. Providing answers to such questions and prying open the mind of the reader is the great service and invaluable gift of this largely unassuming autobiography.

Zeckendorf’s career in Manhattan is practically a history of the borough itself in the half-century after World War II. Though at the beginning it was much less grand, consisting as it did of buying up and restoring run-down hotels that, by the 1960s, were scarcely a shell of what they had been in their glory days, starting with the Mayfair Hotel on Park Avenue and 65th Street. He went on to acquire the Hotel Delmonico (in which he lived for many years) as well as the McAlpin Hotel in Herald Square and the Barbizon Hotel on Lexington and 65th Street.

One of the more interesting subplots of the book concerns a property that he never actually bought. He relates how he and his wife were invited, out of the blue, to visit the home of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon. At one point during their conversation, Moon told Zeckendorf that he wanted to buy a hotel and “declared that he wanted to leave for the city immediately.” One of his assistants organized a caravan of seven Cadillac limousines, stopping on 34th Street when Moon saw a tall building he liked. “Is that a hotel?” Moon asked Zeckendorf. “It was the New Yorker,” Zeckendorf writes, “which had been closed for some time and was in bad shape. ‘I will buy the New Yorker,’ Moon announced.” And so he did, with Zeckendorf’s help. It would subsequently host many of the mass weddings that were the signature events of Moon’s Unification Church.

Most of the book addresses the ground-up buildings that were the core of Zeckendorf Jr.’s career. Readers may be surprised to know that he did not complete his first one — the Columbia— until 1980, when he was over 50 years old.

The Columbia, a residential project, was designed by Frank Williams and became the first of many projects that they would work on together. “Frank became, in effect, my house architect, my I. M Pei [Pei had worked extensively for his father],” Zeckendorf writes.

Though controversial at the time, it was the first project signaling that the area, which had grown increasingly shabby since the Fifties, was turning around. “Central Park West was safe, but in the early 1980s upper Broadway and the side streets were still pretty rough,” the author writes. “All of that was about to change. My vision was to develop the Broadway corridor from West 96th Street down to 14th Street.”

Zeckendorf would go on to develop the elegant Park Belvedere on Columbus and 79th and the Copley just off Columbus Circle. Continuing to revitalize the West Side of Manhattan, he also developed the massive Worldwide Plaza at Eighth Avenue and 49th Street, a four-acre lot consisting of a massive tower designed by David Childs of SOM and a smaller residential tower designed by Williams.

He developed other projects that would be instrumental to reversing neighborhood decay as well, like the massive Zeckendorf Towers that beetle over the east side of Union Square, at the time a needle park.

Zeckendorf even extended his practice to Washington, D.C., building the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, which the author claims is the second-largest development in the city, after the Pentagon. This project, the work of James Freed of Pei Freed Cobb, conceived in the highly neoclassical style that was favored in the mid-1990s, was, architecturally speaking, perhaps his finest achievement. Most of Zeckendorf’s career in ground-up development, which stretched from 1980 to 2000, coincided with the neoclassical strain of postmodernism. But few of those developments approached the excellence of that Washington project.

Zeckendorf’s book leaves the reader with a sense of wonder and appreciation for the under-celebrated art of the real estate developer. Though Zeckendorf spent a large chunk of his career on hotel conversions, he found his stride — and finally stepped out from his father’s shadow. Ironically, it was only when he began to build neighborhood-defining developments that he truly became his father’s son. By the end of the book, one fully understands the motivation that animated its author in the first place. “Why did I find real estate development so compelling?” he writes. “The answer is simple: I wanted to build.”