When the famed Brill Building changed hands for nearly $300 million this summer, its role in 20th Century American popular music was duly noted. But few reports mentioned the man who built it, Abraham Lefcourt.

That would have been inconceivable in the 1920s. Lefcourt, an active developer prior to the Great Depression, at one point held more property than any other Midtown landowner. He lived large, and like many contemporaries, had a tragic fall when the economy collapsed following the 1929 crash.

But while his name may no longer be in the headlines, his legacy still lines Manhattan’s streets. This month, The Real Deal looked back at Lefcourt and other developers who together built some of New York City’s seminal structures.

To be sure, there were many real estate pioneers who left their stamps on New York, perhaps starting with John Jacob Astor, who in the 1830s began purchasing land on what was then the city’s limits, and leasing it out to builders, thus influencing how many residential and industrial neighborhoods were developed. Among the few buildings he built was the Astor House at Broadway and Vesey Street, the city’s first grand hotel.

In his footsteps came men like John Noble Stearns, who in 1889 opened the city’s first skyscraper, the Tower Building at 50 Broadway, to gawking crowds waiting for it to topple in the wind; Harry S. Black, the colorful developer of the 1902 Flatiron Building, then the city’s tallest steel-framed building; Seymour Durst, who led the development of multiple office buildings in both East and West Midtown in the mid-20th Century, and John D. Rockefeller, whose namesake Midtown complex remains an unmatched achievement in urban development.

Others who rightfully belong in the city’s pantheon of memorable developers include affordable-housing builders Abraham Kazan, Frederick Ecker and more modern mavericks like Samuel LeFrak and Fred Trump.

When it was built in 1880, the Dakota stood alone on 72nd Street

But we’ve focused here on seven whose enduring works model trends that are resurgent in the industry today.

These men built precedent-setting luxury apartments, speculative office buildings, enlisted the starchitects of their times and set records for the tallest, largest and most unique properties in the city. Their buildings were not always the first of their kind, but these developers all represented turning points in the city’s growth, and in the growth of the real estate industry, that still resonate with today’s developers. And number crunchers take note: Many of their buildings are still garnering big prices in today’s market.

Edward Cabot Clark

(1811–1882)

In this era of $100 million apartments, it’s hard to imagine that the rich once shunned apartment living. But when Edward Clark started building the Dakota in 1880, the city’s first true luxury apartment building was dubbed “Clark’s Folly.”

Clark earned much of his spectacular fortune (said to be $25 million by the early 1880s, which translates to around $6.53 billion today) as a co-founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Co. Inventor Isaac Singer was the better-known, and named, partner, but Clark’s business acumen was credited for their success. Among his innovations was selling on installment plans, an early form of credit.

Clark started investing in real estate in the 1870s, and took note of the handful of successful middle-class apartment houses, like the Stuyvesant, which stood on 18th Street and is considered New York’s first true apartment building. Clark was inspired to attempt a new venture — an apartment building designed for the upper class.

At the time, apartments were synonymous with tenements, and wealthy society types lived in townhouses, mansions or plush hotels.

Clark spared no expense: The Dakota would cost an unprecedented $1 million to build.

Despite his plans for splendor, though, the location on 72nd Street, far Uptown on the edge of still-incomplete Central Park, “seemed like the North Pole,” wrote Stephen Birmingham in the book, “Life at the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address.” In fact, Birmingham wrote that a friend’s comment that Clark might as well be building in the Dakota territories spawned its name. Extending the joke, Clark instructed prominent architect Henry Hardenbergh to include “Wild West” embellishments on the exterior, including the building’s famous Indian carving.

Birmingham wrote that Clark intended the Dakota to be “a short-cut route to opulent living,” and planned to market not to those dining with the Astors and Belmonts, but to newly minted millionaires with less social status. And seeing the city’s rapid growth, he rightly predicted that 72nd Street wouldn’t seem far away for long.

Clark died two years before the Dakota was complete. His heirs continued the project, and when it opened, the New York Daily News called it, “One of the most perfect apartment houses in the world.” It was fully rented before it opened, and Clark is credited with seeing the future of both apartment living and the Upper West Side, said Donald Albrecht, curator of architecture and design at the Museum of the City of New York.

Now a co-op, the Dakota continues to draw the well-heeled. Last month, a three-bedroom apartment overlooking Central Park sold for $23.5 million.

Frank W. Woolworth

(1852-1919)

Although he made his money in his once-ubiquitous five-and-dime stores, Woolworth’s biggest stamp on New York was the Downtown tower that bears his name.

The skyscraper as we know it was already well established when Woolworth started his project, said Francis Morrone, a professor at New York University and author of “New York City Landmarks,” which features the Woolworth on its cover. In fact, the 11-story Tower Building, built in 1889, a few blocks north, was demolished in late 1913, a few months after the Woolworth opened.

But from the crafty land assemblage labeled a “realty triumph” for Woolworth’s agent, Edward Hogen (who spent $4.5 million acquiring the parcels), to its record-setting height, the building had lasting impact.

Designed by one of the era’s starchitects, Cass Gilbert, it was originally planned as 30 stories, but grew to 57, while the budget climbed to $13.5 million.

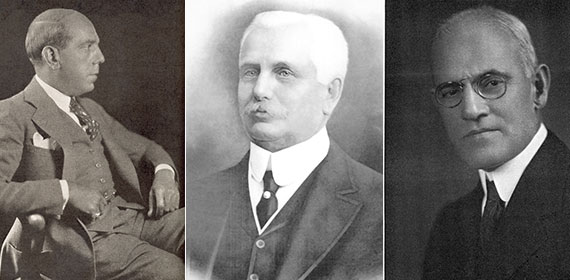

From left: Abraham Lefcourt, Frank W. Woolworth and Alexander Bing

The neo-Gothic structure was a sensation at its debut. Clad in gleaming white architectural terra-cotta (much of it removed during subsequent renovations), and with a gilded roof stretching to 792 feet, it surpassed the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower as the tallest building in the world.

It was a “soaring symbol of American pride” at a time when the nation was taking its place among the world’s great powers, Morrone noted in his book. On April 24, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button in Washington D.C. to illuminate its 5,000-plus windows for the first time.

“This building and the success of its owner shows that this is the land of equal opportunities; that a man may start with nothing and accomplish everything,” Gilbert said at the opening ceremony for the building dubbed “The Cathedral of Commerce,” for its resemblance to European cathedrals and its ornate lobby.

Also notable is that the Woolworth Building was built largely on speculation. At the time, companies building high-profile towers did so for their own use. But the dime-store operator occupied just two floors, enabling Woolworth to profit from renting the rest.

“I saw possibilities of making this the greatest income producing property in which I could invest my money,” Woolworth told a newspaper in 1912. Among the first tenants were the Irving National Exchange Bank and Columbia Records.

The landmarked property was owned by the Woolworth Co. until 1998, when, less than a year after the last five-and-dime closed, its successor company sold it to the Witkoff Group for $155 million.

Today, it’s part of another significant New York trend: its top 30 floors are being converted into super-luxury condos by Alchemy Properties, which purchased the upper reaches of the building in 2012 for $68 million. The 9,400-square-foot penthouse, dubbed the “Pinnacle,” is being marketed for $110 million.

Abraham Lefcourt

(1877-1932)

Lefcourt started his development career by building a “towering” 12-story garment factory at 48-54 West 25th Street in 1910.

By 1924, the one-time shoeshine boy owned much of the area between 35th and 39th streets west of Broadway, valued at over $100 million (that would be a staggering $7.07 billion today).

By 1930, he had completed 31 buildings, 20 in Manhattan, including lofts, apartment buildings and office towers. His total investment came to “well over a quarter of a billion dollars,” the New York Times wrote in 1930. Many of his structures bore his name, including the 26-story Lefcourt Clothing Center at Seventh Avenue and 25th Street, which became the anchor for the Garment District. The landmark Essex House on Central Park South is one of at least 17 of his buildings that remain.

“No other single individual or building organization has constructed … as many buildings as are in the Lefcourt group,” the 1930 Times story said.

Jason Cochran, a journalist and self-described pop historian, called Lefcourt, “The Donald Trump of Roaring ‘20s Manhattan,” for his flamboyant lifestyle, high-profile developments and the fact that “he grandly affixed his own name to many of them to secure his own reputation.” The developer even started his own bank, the Lefcourt Normandie National Bank, in 1928.

But Lefcourt’s 32nd project at Broadway and 49th Street, on a property sublet from the Brill Brothers, a men’s clothing store, was a turning point.

At the start of construction in 1929, he declared it would be the world’s tallest, though no plans were filed to show how that might be accomplished. Instead, his effort to compete with the Chrysler Building and Empire State Building, which were both rising at the time, was tinged with tragedy. By 1930, the Great Depression was draining his wealth and Lefcourt faced heartbreak in the death of his 17-year-old son, Alan.

The Woolworth Building around its opening in 1913

Instead of building the world’s tallest building, he filed plans for a 10-story Art Deco office building. He named his last property the Lefcourt-Alan Building.

By 1931, Lefcourt had defaulted on his sublease and the Brills took over the property. The building took their name, though it still bears a bronze bust of Alan over the door.

Lefcourt died suddenly the following year in another of his buildings, the Savoy-Plaza Hotel, which was demolished in 1956 to make way for the GM Building. According to the Times, he had just $2,789 left to his name, none of it in real estate.

Alexander Bing

(1879-1959)

Working with his brother, Leo, Alexander Bing was the business mind behind the firm Bing & Bing, one of New York City’s most prolific developers. Between 1906 and 1921, the pair built more than three dozen apartment buildings and hotels.

The properties, many of which were designed by prominent architect Emery Roth, featured spacious units in some of the city’s prime neighborhoods and are considered the very definition of “pre-war classic.” Among them were the Alden, at 82nd and Central Park West, the Southgate apartment complex on East 52nd Street, 2 Horatio Street in the West Village and the Gramercy Park Hotel.

The Bings “made their names synonymous with stately, spacious apartments in elegantly detailed buildings that often had Art Deco touches,” the New York Times wrote in a 2006 feature on their Upper East Side buildings.

“Sometimes, you’ll find in a real estate ad even now, a ‘Bing & Bing building,’” noted the Museum of the City of New York’s Albrecht.

At 1000 Park Avenue, the two carved figures in medieval dress near the main entrance of their apartment building are said to be “portraits” of the brothers.

But their prolific production for the gentry was just a part of the legacy.

Alexander Bing retired from the family firm in 1921 to get involved in developing lower-income communities. In the early 1920s, he provided funding for the City Housing Corporation of New York City, which built Sunnyside Gardens in Queens, and the planned community of Radburn in New Jersey, which introduced concepts like the cul-de-sac and interior parklands. He was also a patron of the arts and a renowned philanthropist.

Bing & Bing continued to manage many of the founders’ properties until the mid-1980s, when the family’s heirs sold them in several transactions, including a block of 29 buildings that in 1985 went for more than $250 million to a partnership led by real estate firm

M.J. Raynes.

Fred F. French

(1883-1936)

Born into poverty, Fred F. French had to go to work as a young boy, selling newspapers and doing odd jobs to help support his family. Yet he also managed to stay in school, and eventually study engineering at Columbia University. When he died, he would be credited with building some of the most significant residential developments of the 20th Century, along with several notable office towers.

French led an expansive lifestyle. And he once famously said, “You can’t overbuild in New York.”

In 1925, he undertook Manhattan’s largest-ever housing project, on five acres along the East River in the 40s. His plan was to build a $25 million “urban Utopia” of parks, gardens and neo-Gothic apartment buildings in an area dominated until then by slums, tenements and slaughterhouses. His aim was to provide affordable housing for office workers then fleeing Manhattan for the outer boroughs and the suburbs.

The project, called Tudor City, saw its first building open in 1927. Considered the world’s first residential skyscraper complex, it included 11 high-rises, four brownstones and a hotel, with roughly 3,000 units when complete.

Although there are still a good number of rental tenants, the properties, now across the street from the United Nations’ headquarters, went co-op in 1984.

Although there are still a good number of rental tenants, the properties, now across the street from the United Nations’ headquarters, went co-op in 1984.

By 1934, French was also at work building Knickerbocker Village, a multi-building complex for the working class on the site of another notorious slum between the Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges. It was one of the first federally subsidized urban renewal projects to be privately built and owned.

French also built several office towers, notably the Art Deco French Building at 45th Street and Fifth Avenue.

Among his innovations was the use of investment capital from individual investors, who purchased equity shares in his projects and were paid dividends before the developer took any profits.

Erwin Wolfson

(1902-1962)

Shortly before he died, a cancer-ridden Erwin Wolfson inspected the progress of construction on his greatest project by flying over the site of the Pan Am Building in a helicopter.

The prolific builder was deeply involved in the details of his massive creation. He worked out a unique foreign financing deal with British investors when he couldn’t get a U.S. bank to loan him enough money to build what was then the world’s largest commercial office building. And he personally negotiated the lease for 15 floors with the now-defunct airline whose name the building wore for two decades, saving $1 million or more in commissions in the process. A group led by Tishman Speyer bought the building in 2005 for $1.72 billion, a record price at the time for an office building.

The Pan Am Building, which he didn’t survive to see debut, was only one of the dozens of Manhattan office buildings, apartments and other structures Wolfson left as his legacy.

He got his start in real estate when he bought two lots in Florida while vacationing in the mid-1920s. On one, he spent $6,500 to build a house he then sold for $20,000. He went on to earn a small fortune building residential and commercial properties, but lost it when a Florida land bubble burst just a few years later.

Wolfson then moved to New York and took a low-level construction crew job. Not 10 years later, he was directing construction at upwards of 20 office-building projects for the Adelson Real Estate company.

Then in 1936, he co- founded the Diesel Electric Company to install power plants in buildings. A year later, the firm changed course and began constructing its own buildings.

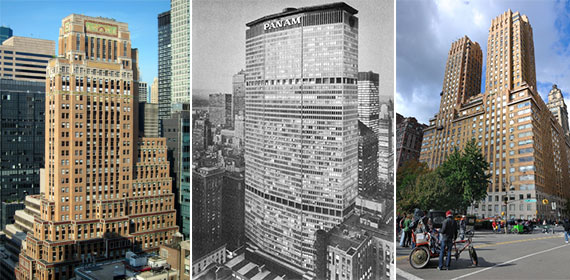

From left: The Fred French building on 45th Street, the Pan Am building and Irwin Chanin’s Majestic Apartments

Diesel led construction of multiple towers, including massive block-filling office buildings like the 20-story 100 Church Street, designed by Emery Roth; 30 Broadway; 579 and 589 Fifth Avenue, and the Bankers Trust Building at 529 Fifth Avenue.

At the same time, Wolfson had a parallel career as an investment builder, putting up buildings he held a financial interest in. His New York Times obituary credited him with independently putting up 6 million square feet of office buildings in the city. He was also an active builder in Chicago, Philadelphia, Memphis and Denver.

Irwin Chanin

(1891-1988)

Irwin Chanin had a theatrical flair that extended beyond his construction of several of Broadway’s landmark theaters, but he first made his mark on the Great White Way.

After a stint with his brother Henry building homes in Brooklyn, the Chanins built six playhouses in the 1920s that today remain the core of the Theater District: Theatre Masque (now the Golden), the Royale (now the Bernard B. Jacobs), the Majestic; the 46th Street (now the Richard Rodgers); the Biltmore (now the Samuel J. Friedman) and

the Mansfield (now the Brooks Atkinson). The brothers also built the Roxy, a grand movie palace on 50th Street demolished in 1960.

Irwin Chanin was listed as the architect of record on a number of his buildings.

Also among Chanin’s lasting contributions are two monumental, landmarked apartment complexes on Central Park West: the Majestic, built in 1930, and the Century, built in 1932. There’s also the Chanin Building on 42nd Street at Lexington Avenue.

Chanin “understood the fact that architecture is a performing art,” the New York Times once wrote. It called the two twin-towered apartment buildings “the ultimate in urban sophistication,” and said the Art Deco office tower “epitomized Chanin’s vision of modern architecture as a theatrical setting for a dynamic society.”

“He wanted something that had more meaning than just putting a building there,” said Cooper Union professor Diana Agrest, who wrote a book about Chanin when the architecture school at his alma mater was renamed in his honor in 1981.

Chanin also built the Lincoln Hotel on Eighth Avenue, long known as the Milford Plaza, which was sold in 2013 for $325 million, and is now called the Row NYC. Other projects included 1411 Broadway, and the Beacon Theatre on the Upper West Side.