UPDATED, Nov. 24, 1:45 p.m.: When the pandemic hit in March, affordable housing investment firm Yes Communities was negotiating a deal to purchase a portfolio of mobile-home communities across the country for more than $1 billion.

UPDATED, Nov. 24, 1:45 p.m.: When the pandemic hit in March, affordable housing investment firm Yes Communities was negotiating a deal to purchase a portfolio of mobile-home communities across the country for more than $1 billion.

But the sale posed a significant challenge at a time when many government offices were closed and in-person meetings were off the table: Denver-based Yes couldn’t record the mortgages because government offices in the states the 49 properties were spread across had been closed.

“They had essentially gone hard, and the whole deal needed to be pieced back together again,” said Ness Cohen, chair of the national real estate practice at the global law firm Clifford Chance, who represented the buyer on the deal.

Cohen said that ultimately his client and the seller were able to sit down with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and seal the deal in June. But the rocky road to closing was indicative of how many deals went sideways in the early months of the crisis.

“A lot of business pivoted toward keeping transactions alive,” he said.

It’s been a tumultuous eight months for the legal eagles who dot the i’s and cross the t’s on tens of billions of dollars’ worth of real estate deals each year. The attorneys who rely on a regular churn of sale and financing transactions saw that deal flow grind to a halt in major markets like New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago.

Landlord and tenant attorneys have been effectively locked out of housing court rooms for months.

In New York, for example, as tenant advocates protested the reopening of housing court in June, some 100 attorneys from the Brooklyn Housing Court Bar Association mulled the idea of a public demonstration outside the Barclays Center on behalf of landlords unable to evict non-paying tenants during the pandemic.

And lawyers who specialize in areas like foreclosure and distress are, by and large, still waiting for a rush of work many believe has been put off by government bailout measures.

And lawyers who specialize in areas like foreclosure and distress are, by and large, still waiting for a rush of work many believe has been put off by government bailout measures.

In the meantime, some are finding work handling loan forbearance agreements and workouts or negotiating settlements outside of court between landlords and tenants. It’s also true that the regular rhythms of the legal business — such as client-building power lunches and the annual rush of recruiting after bonuses are paid out early in the year — have been disrupted.

With that backdrop in mind, The Real Deal compiled its annual ranking of the top real estate law practices in New York, one of the biggest markets in the country for both the legal and real estate industries.

One thing that’s certain is that nothing about their work is routine in 2020.

Jay Neveloff, head of the real estate group at New York-based Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, acknowledged the personal struggles many are going through in the midst of a health and economic crisis. From a legal perspective, he said, it’s forced everyone to sharpen their skills and come up with unique solutions.

“There’s no uniform approach,” Neveloff said. “It’s actually kind of fun.”

Survival of the busiest

Not surprisingly, the city’s leading law firms on real estate sales and financing deals saw their overall activity drop this year.

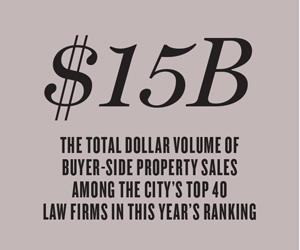

All told, the 40 most active firms handled about $15.3 billion in buyer-side sales from September 2019 through September 2020, down from $24.8 billion among the top 30 in last year’s ranking.

On the debt side, the total dollar volume among the 40 leading firms fell to $26.2 billion on lender-side loans, down from $69.5 billion among the top 30 in the same time frame. It should be noted that last year’s ranking included both mortgage documents and agreements, while this year’s was based solely on mortgage documents to avoid potentially inflated figures. That applied to all firms across the board.

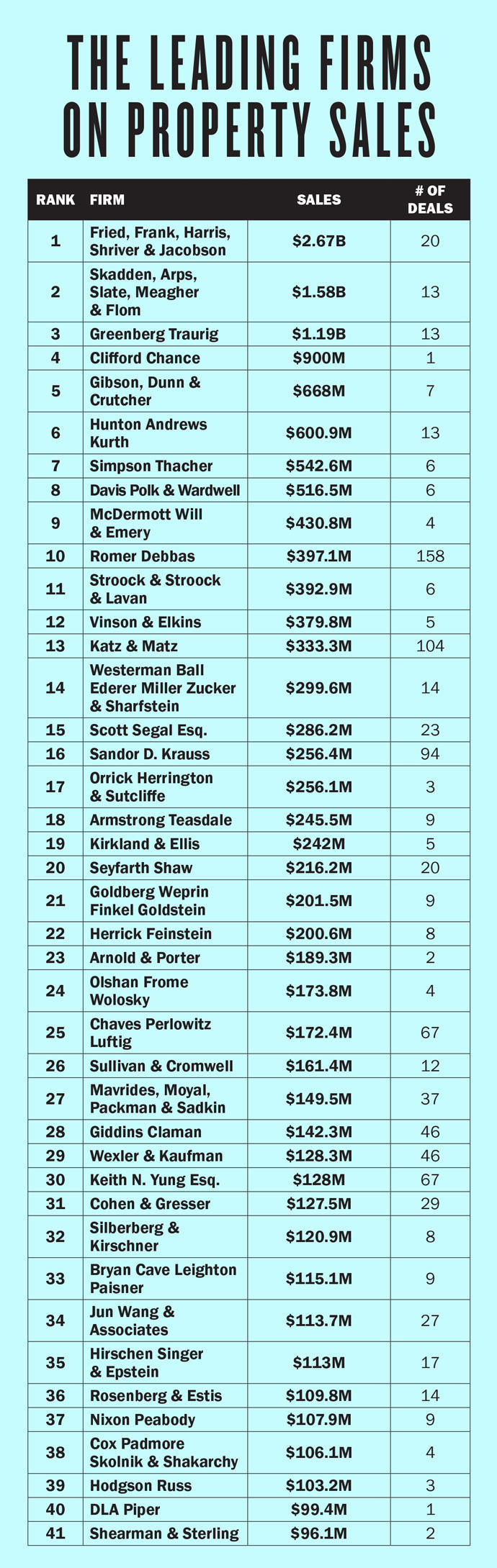

Source: TRD ANALYSIS OF NYC BUILDING SALES THAT CLOSED BETWEEN SEPT. 1, 2019, AND SEPT. 30, 2020, AND WERE RECORDED IN ACRIS. ONLY TRANSACTIONS OF $1 MILLION OR MORE WERE INCLUDED, AND LAW FIRMS WERE ONLY CREDITED FOR DEALS IN WHICH THEY REPRESENTED THE BUYER. FIRMS WERE PROVIDED DATA FOR CONFIRMATION, BUT NOT ALL RESPONDED.

On the sales front, perennial powerhouse Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson took the top spot again this year with a total of $2.67 billion in buyer-side sales. The global law firm was followed by Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom with $1.58 billion in sales, while Greenberg Traurig took third place with $1.19 billion. Clifford Chance landed at No. 4 with $900 million, and Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher rounded out the top five with $668 million.

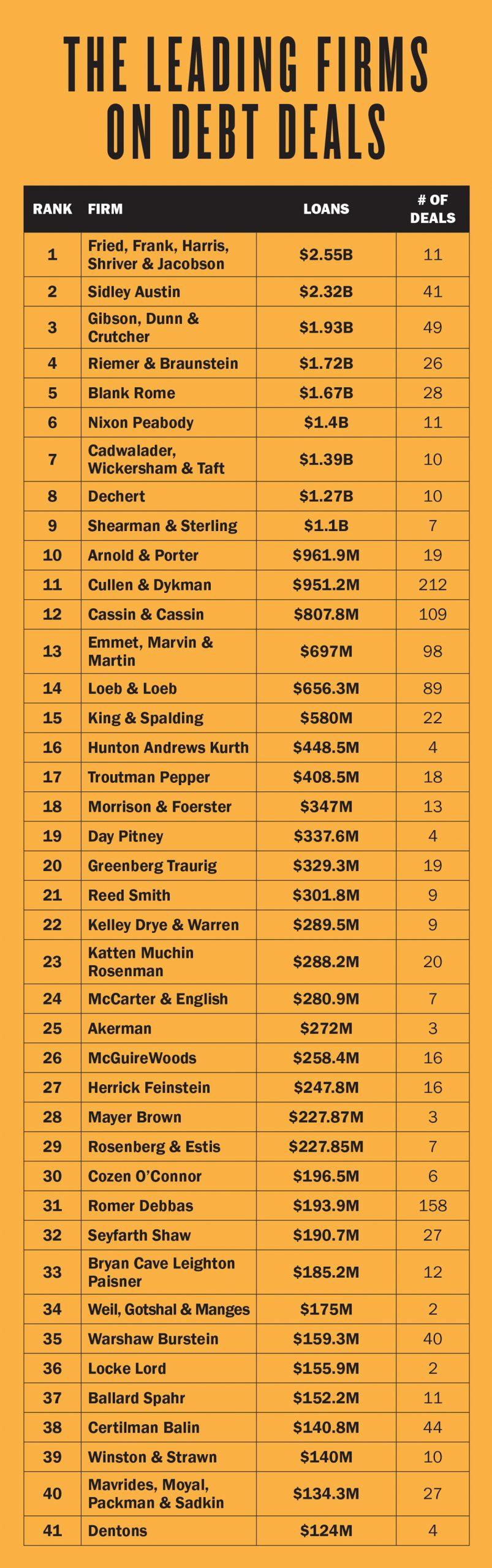

On debt deals, Fried Frank also came in first on this year’s ranking with a total of $2.55 billion in lender-side mortgages, followed by Sidley Austin with $2.32 billion and Gibson Dunn with $1.93 billion. Riemer & Braunstein came in fourth with $1.72 billion, while Blank Rome took the No. 5 spot with $1.67 billion.

Stephen Rabinowitz, co-chair of Greenberg Traurig’s global real estate group, said that while the number of sales transactions has been down, lawyers have been busy counseling their clients on properties.

While some notable buildings like Midtown’s Hilton Times Square and Roosevelt Hotel have completely shuttered, other real estate assets in the Big Apple are actively leasing, trading and taking on new debt and equity.

“It’s been a lot of pulling out old sets of documents and finding out what we can do to protect our clients,” said Rabinowitz. His recent deals include SL Green’s contract with the 601W Companies in early November to sell its Amazon-anchored office building at 410 10th Avenue in Hudson Yards for roughly $950 million — the largest commercial real estate deal since the start of the pandemic.

Attorneys who represent borrowers and lenders said that where activity has dropped off on new loan originations, they’ve picked up work negotiating forbearances and loan restructurings. About $30 billion worth of CMBS loans had been granted forbearances as of November, according to data firm Trepp.

Attorneys who represent borrowers and lenders said that where activity has dropped off on new loan originations, they’ve picked up work negotiating forbearances and loan restructurings. About $30 billion worth of CMBS loans had been granted forbearances as of November, according to data firm Trepp.

But when it comes to the wave of distressed loans that many were expecting to wash over the New York City market — due to shuttered hotels, empty office buildings and a glut of vacant retail — some industry attorneys say that has yet to hit.

“I thought we’d be dealing with workouts, litigation and bankruptcies all year,” said Gibson Dunn attorney Noam Haberman. “It’s somewhat refreshing that hasn’t been the case. It’s been more counseling on existing deals.”

Michael Hurley, a partner at the real estate law firm Cassin & Cassin, echoed that sentiment. “We’re just not seeing as much as we thought we’d see,” he noted.

Hurley added that his firm has been working on a lot of modified and extended debt deals that involve “new money,” some of which were not included in this ranking because they were recorded with the city’s Finance Department as agreements rather than mortgage documents.

“We’ve done significantly more new originations on the loan side than I would have expected, which I think is attributable to the fact that interest rates are at an all-time low,” Hurley said.

Private affairs

Law firms are private companies and therefore don’t report earnings like their publicly traded counterparts.

So, while it’s clear to see how the pandemic has impacted large commercial brokerages and real estate investment trusts through a dropoff in earnings, it’s harder to quantify the impact on law practices.

SOURCE: TRD ANALYSIS OF NYC MORTGAGES THAT CLOSED BETWEEN SEPT. 1, 2019, AND SEPT. 30, 2020, AND WERE RECORDED AS MORTGAGE DOCUMENTS IN ACRIS. ONLY TRANSACTIONS OF $1 MILLION OR MORE WERE INCLUDED, AND LAW FIRMS WERE ONLY CREDITED FOR DEALS IN WHICH THEY REPRESENTED THE LENDER. FIRMS WERE PROVIDED DATA FOR CONFIRMATION, BUT NOT ALL RESPONDED.

But attorneys who spoke to TRD said their business is either flat or down by about 10 percent.

Others are gearing up for the distress that has yet to arrive en masse.

Michael Lefkowitz, managing member of the New York real estate law firm Rosenberg & Estis, for one, said his company recently brought on a small group of three bankruptcy attorneys to start growing the firm’s work in that space. The move predates the pandemic, he noted, but is one that should prove useful as more companies go under.

Another large area of work for the firm — its landlord and tenant practice — took a hit as courts closed this year amid eviction bans. Lefkowitz said it will be challenging to resume that work when courts get back to business. Housing courts are allowing some cases to proceed, but the vast majority of eviction cases won’t be heard until January at the earliest.

“I think the bottleneck will be cause for both the landlord and tenant side to negotiate settlements rather than waiting on the courts to decide the case,” he said.

In addition to restrictions on evictions coming out of Albany and Washington, D.C., there are a number of other regulatory issues complicating the real estate landscape.

After forcing many businesses to close their doors for months in the spring and summer, for instance, Gov. Andrew Cuomo imposed a 10 p.m. statewide curfew on New York restaurants, bars and gyms in mid-November to curb a surge in new Covid cases.

Robin Cohen, head of the insurance recovery practice at McKool Smith, said she’s seeing a lot more work from real estate companies trying to get their insurance firms to cover business interruption losses under their policies.

“You’ve got a lot of policyholders seeking payment,” she said.

“You’ve got a lot of policyholders seeking payment,” she said.

Distant socializing

In New York City, the height of the holiday party season is the annual bash hosted by Fried Frank at Cipriani’s in Midtown, which draws the biggest names in the industry.

It’s not just a party — it’s the event to be seen at in a business where elbow-rubbing and glad-handing grease the wheels of multimillion-dollar deals.

This year, understandably, it has been called off.

“We spent a lot of time thinking about another way to do it,” said Fried Frank’s real estate chair, Jonathan Mechanic, who gregariously hosts the event each year. “It’s just too complicated when you think about 1,200 or 1,300 people. Zoom would crash.”

Not only did the pandemic throw a wrench in the works of the city’s transaction pipeline, it also disrupted the networking aspect of the business. Mechanic said that since the Fried Frank office opened back up, he’s been having lunch with clients at Midtown restaurants like Casa Lever and Estiatorio Milos.

But Mechanic, who worked with Brookfield Property Partners on a $1.8 billion refinancing of One Manhattan West in September, said it’s not the same as visiting clients in their offices. “I think people are being protective of their offices — knowing who’s coming in and out,” he said.

It’s one of many adjustments attorneys have had to make to working from home.

Department heads at firms with large national or international practices said their attorneys are used to working with clients who visit the city infrequently in normal times. By and large, they said, their colleagues have adapted well to their home offices.

Lawyers for the most part have their own offices, so social distancing within a law firm is easier than, say, on a trading floor or in a tightly packed tech office.

But some things have been put off.

January is the early part of the year when law firms generally recruit attorneys who have just received their bonuses, and many said that didn’t happen this year. Some firms have delayed their on-campus recruiting activities at law schools this year.

Wayne Cook, a partner at the New York law firm Windels Marx, said Covid fatigue is setting in.

“It’s difficult to create new relationships if you’re not out there,” Cook said. “I think it is difficult, but everybody’s in the same boat.”