While the 52-story tower at 270 Park Avenue is set to be demolished in the coming year, one thing that will not get destroyed with the building is the legacy of the woman who designed it.

During a time when men dominated, Natalie Griffin de Blois was the lead architect of the iconic mid-20th-century glass-and-steel office tower, which was finished in 1961 and stands in the heart of Midtown.

The current owner and occupant of 270 Park, the megabank JPMorgan Chase, announced in February that it would raze the skyscraper and replace it with a soaring 70-story, yet-to-be-designed corporate headquarters.

The move is a product of the controversial 2017 rezoning of Midtown East — a 78-block area near Grand Central Terminal. The rezoning allows for taller buildings and the sale of unused air rights over landmark structures. The rights can also be sold across the neighborhood and not just between adjacent buildings, as is the case elsewhere.

JPMorgan bought more than 700,000 square feet of air rights — including 680,000 square feet from Grand Central for $240 million — to make way for its new $4 billion tower. The 1,200-foot supertall could be the first in a wave of modern buildings that could collectively remake the aging Midtown office market.

But the development, which is expected to be completed in 2024, has also put a spotlight on de Blois, who despite her accomplished career never won full partner status at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

“SOM claimed to design the buildings, but Natalie really did,” said Cynthia Phifer Kracauer, an architect and the executive director of the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, a nonprofit that raises awareness about the contributions of women in architecture.

“Women never get enough credit,” Kracauer added.

Bending gender roles

Born Natalie Griffin in 1921 in Ridgewood, New Jersey, to Harold, a civil engineer, and Cornelia, a teacher, de Blois was encouraged from an early age to blaze her own path.

Lever House

In junior high school, she refused to take sewing and cooking classes, then required of girls. Instead, with the advocacy of her father, she insisted on taking mechanical drawing, according to a 2002 oral history at the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Her interest in buildings was cemented in 1935, when at 14 years old, she visited the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in Manhattan with her Sunday school class. Inside stood a life-sized, three-story tenement building that was part of an exhibit about “slum clearance.”

“It just struck me that my interest in architecture broadened seeing that exhibition,” she later said.

Her fascination with the city and its architecture led her to Columbia’s University’s school of architecture, where she received her degree in 1944. Just five of the 18 students in her class were women. That was a seemingly high percentage at the time, but many men were away fighting in World War II.

Upon graduating, de Blois joined the now-defunct, retail-focused architecture firm Ketchum, Gina and Sharp. But her presence in the male-dominated world of architecture — one report out of the U.S. Department of Labor found that women only made up 2 percent of the profession in the 1940s — was not always well received.

Some of her male colleagues never seemed to reconcile her professional abilities with her gender.

A Ketchum colleague, for example, would take her dancing at Benny Goodman concerts, but when she rebuffed his romantic advances he allegedly complained to the company that he could no longer work with her. The firm ultimately fired de Blois.

“I didn’t realize that things like that happened,” de Blois said. “I took this first shock — and there were many more of them — I took them personally.”

Soaring at SOM

If there was a silver lining, it was that Morris Ketchum, the boss who fired her, quickly landed her a job at SOM, just one floor below her old firm. And there de Blois quietly became a prolific architect of big buildings in major cities.

Her most prominent works are the corporate Modernist buildings raised on Park Avenue during the “Mad Men” era.

Her projects include Lever House at 390 Park Avenue, the luminous blue-green 21-story office building that was completed in 1952. She was also instrumental in the design of the Pepsi-Cola Building at 500 Park.

Her projects include Lever House at 390 Park Avenue, the luminous blue-green 21-story office building that was completed in 1952. She was also instrumental in the design of the Pepsi-Cola Building at 500 Park.

And she was involved in the designs of the Hilton Hotel in Istanbul, the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati and the Equitable Building in Chicago, among others.

More locally, she designed the Abraham Lincoln Houses, a 14-building public housing development in East Harlem; a cliffside co-op known as the Horizon House in Fort Lee, New Jersey; and the bathhouses at Jones Beach State Park.

And she helped shape the United Nations and Lincoln Center, she said. For those two projects, SOM partnered with Harrison and Abramowitz, the official architect of record.

But it was 270 Park Avenue that raised her profile the most. The soon-to-be-leveled building — for which she served as “project designer” — was created as the headquarters of Union Carbide, the chemical company behind Prestone antifreeze and Eveready batteries. The full-block East 47th Street building, whose steel mullions jut out like fins, has 11 acres of glass windows and 19 miles worth of black stainless steel, according to a brochure that’s included in a collection dedicated to de Blois at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

The 712-foot-tall tower, which also has a plaza and 13-story wing, was the ninth-tallest building in New York City when it was completed, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, a research group. But it was never landmarked.

The price tag to construct it was a hefty $80 million — the equivalent of $674 million today. And since its construction, it’s changed hands several times.

In 1981, Union Carbide sold the building to the bank Manufacturers Hanover, which redesigned the plaza and lobby, removed cubicles and added elevators. Chase took over in 2000 and, in 2011, renovated the building to make it more eco-friendly, adding planted roofs, new cooling systems and a 54,000-gallon tank to collect rainwater for use in bathrooms.

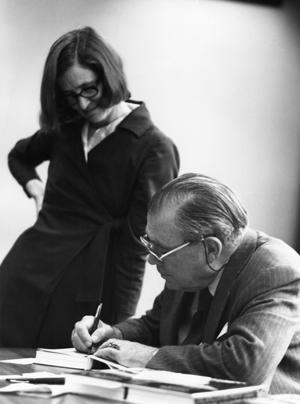

De Blois with architect Myron Goldsmith

But the Midtown East rezoning put the nail in the building’s coffin when it put a massive amount of air rights in play. In addition to the square footage JPMorgan bought from Grand Central, it also paid $21 million to St. Bartholomew’s Church for 50,000 square feet.

The bank — which was required to contribute millions of dollars toward transit improvements in the area as part of the air-rights deal — is set to start construction next year. The new building will accommodate its 15,000 employees, who are now spread out among several buildings.

Standard sexism

After the completion of 270 Park, de Blois departed for a 13-year stint at SOM’s Chicago office. But it took three more years for the firm to finally elevate her to an associate partner in 1964.

De Blois left SOM in 1974 having never received the coveted senior partner title. “I think [the firm’s] theory was there’s not going to be any women partners, ever,” she later said.

Throughout an impressively long and storied career, de Blois continually faced hurdles. Colleagues regularly excluded her from male-only lunches, she said. And she said one of her frequent collaborators (an SOM partner) once asked her not to attend a ribbon-cutting ceremony because she looked too pregnant.

Despite that reality, de Bois went on to have four children — all boys. With three of them, she returned to work just one week after they were born. In addition, having divorced in 1960, she mostly raised all four children by herself.

In a 2004 interview for the SOM Journal, an in-house periodical, she also recalled how the aforementioned SOM partner, Gordon Bunshaft, once asked her to leave her sons in the car during a business meeting. “His treatment of me as a woman was typical at that time,” she said.

But de Blois never complained and rarely spoke of her family — or role as the primary caregiver — for fear she might get fired or be further ostracized. Her family life was so separate from her work life that she “didn’t have any pictures of my children on my desk,” she once told an interviewer.

Still, Bunshaft had moments of professional support —recommending her for an architectural Fulbright fellowship in Europe, which she won in 1951 to research Auguste Perret, an architect known for his postwar buildings.

By the 1970s, de Blois seemed eager to tackle some of the industry’s ingrained sexism. She co-founded Chicago Women in Architecture, an advocacy group, and began working with the American Institute of Architects to push for less-offensive language in advertising, such as removing references to women as the “weaker sex.”

De Blois said she worked on Lincoln Center with Harrison and Abramowitz, the complex’s architect of record

“I admire her enormously,” said Deborah Berke, the founding partner an eponymous Manhattan-based firm whose portfolio includes 48 Bond Street and the interiors at 432 Park Avenue. (Berke also recently won a competition to design the Women’s Building, a prison-to-office-building conversion in West Chelsea.)

“Her work is beautiful, it is handsomely detailed and it has a rigor that I cherish,” she said, noting that the Pepsi-Cola Building is one of her favorite structures in New York.

A lasting legacy

In the late 1970s, de Blois moved to Texas to work for the now-defunct Neuhaus and Taylor in Houston while also teaching at the University of Houston.

Then in 1980 she relocated to Austin, where she worked part-time for a firm crafting the city’s downtown zoning. While there, she also taught architecture at the University of Texas. But her salary was not on par with her male counterparts’, she said. (The school later created a scholarship in her honor.)

De Blois never stopped reflecting on working conditions for women.

“The discriminatory actions by men still exist. Some men are just awful,” she told an interviewer in 2002. “There are people you just have to stay clear of. You can’t cope with them.”

As for the industry’s gender landscape today, Berke, who began practicing in the 1980s, put it this way: “It was bad then, and it’s still pretty bad.”

She added that even though women now make up 50 percent of students at architecture schools, “they don’t stay in the field, and that’s a shame.”

Elizabeth Harrison Kubany, a spokeswoman for SOM, acknowledged that de Blois — who died of cancer in 2013 at age 92 — never received her due recognition. Kubany called her “an extraordinary talent” and noted that she left “an indelible mark on SOM and the entire profession in the 1950s and ’60s, a time when there were very few women working as architects.”

“It is perhaps a sign of the times that she was never made a partner,” Kubany said. “If she were working today, she would almost certainly be a partner at the firm.”