Stellar Management’s Larry Gluck was not pleased to learn earlier this year that tenants of his Chelsea apartment building were renting out their $3,500-a-month apartment via Airbnb on an almost nightly basis. Charging $375 a pop, the tenants were poised to net $11,000 a month, according to a lawsuit filed by Stellar in August, which detailed how the firm monitored short-term rental sites to quash such behavior.

But even while landlords like Stellar crack down on tenants renting through Airbnb, the home-rental site’s spectacular rise has breathed new life into the city’s short-term rental market, despite local housing laws that prohibit sublets of less than 30 days.

“The real estate industry is salivating over the opportunity, which is enormous,” said Jeffrey Schleider, CEO of residential brokerage Miron Properties, who represents several developers looking to capitalize on the Airbnb phenomenon.

In short, there’s big money in short-term rentals.

Since launching in 2008, San Francisco-based Airbnb has raised $1.5 billion in private funding and now boasts a $25.5 billion valuation. It is expected to pull in revenue of $850 million this year, up from $250 million in 2013, according to published reports.

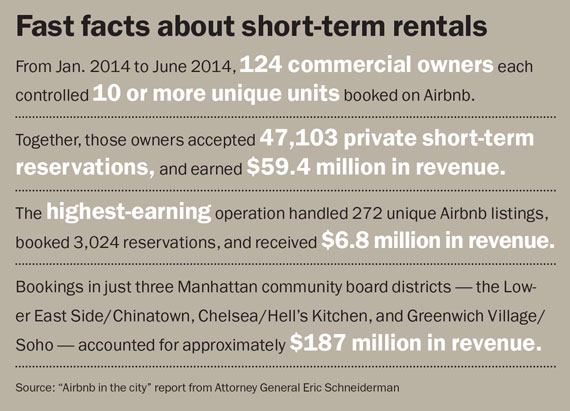

In New York City, Airbnb bookings spiked between 2010 and 2014, according to a report by state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman’s office, which has cracked down on the home-rental site because owners frequently skirt the law when renting out apartments. The report found that Airbnb and local hosts made $282 million from stays booked between 2010 and 2014. There were more than 100 hosts who turned Airbnb into their private businesses, generating nearly $60 million in revenue. The highest-earning of them managed 272 listings, booked more than 3,000 reservations and took home $6.8 million.

“There’s always demand for short-term housing in Manhattan, because people come from all different areas to work here,” said Gary Malin, president of the rental-focused brokerage Citi Habitats. “And they’ll pay dearly for it.”

Still, New York City’s short-term rental market is extremely fragmented. Before sites like Airbnb came along, the market was dominated by companies like Manhattan-based Oakwood, which caters to corporate clients, and local furnished apartment rental companies like Furnished Quarters and Furnished Dwellings.

As for landlords, many prefer to stay away from the headaches of short-term rentals, including juggling bookings and frequent maintenance. “There’s just so much management,” said Douglas Wagner, head of brokerage services for Bond New York, who noted brokers also earn smaller commissions on short-term leases.

But a number of landlords and brokers are learning that there’s money to be made by offering a limited number of short-term rentals. “There’s such a huge need for it,” said Phil Horigan, a Corcoran Group agent who in 2013 launched Leasebreak.com, a site geared toward short-term rentals that now has nearly 600 listings.

Developers are also creeping into the market.

At the Arthur, a 68-unit luxury rental building at 245 West 25th Street, developer Miki Naftali’s Naftali Group is renting two model units for between four and 12 months, according to Compass’ Jason Saft, the exclusive leasing agent for the property. “We made the decision to lease the furnished models, because we kept getting demand for it,” Saft said. “We thought, ‘Let’s explore this.’”

Jason Saft

Saft said that when owners have flexibility, they can demand a premium – both because it’s furnished and because it’s for a shorter term. At the Arthur, for example, a one-bedroom model unit is asking $7,000 a month, compared with a typical one-bedroom asking $5,500 a month.

Similarly, at 50 United Nations Plaza, the new owner of a three-bedroom condo is trying to rent out the apartment for $26,950 a month for a year-long lease, or $33,000 a month for a six-month lease. Zeckendorf Development, which developed the 88-unit residential tower in Turtle Bay, is one of few developers to allow six-month rentals, and the building had eight condos for rent as of Sept. 15, according to StreetEasy.

“It is uncommon for this type of building,” said Nest Seekers International’s Jessica Campbell, who is representing the new owner of the three-bedroom condo. The apartment went into contract in July, with an asking price of $3.865 million. “The owner has no intention of living there,” she said. The rental income “will cover the monthly charges and as time goes on, the property’s sales value will increase and at some point he’ll sell it.”

Hoping to partner with more owners, hospitality startup onefinestay, which bills itself as an upscale Airbnb, recently started negotiating with condo and co-op boards about renting out units in a way that complies with the city’s housing and hotel regulations. Participating boards would get a share of the proceeds, said onefinestay co-founder Evan Frank. “Institutions in New York are beginning to realize that the sharing economy is a trend that they may want to figure out how to be part of, versus a fringe trend that’s going to go away,” Frank said.

Rodrigo Niño

To that end, Pennsylvania-based Korman Communities, which operates AKA, a luxury extended-stay hotel brand, is converting two of its five New York City hotels into condos, where buyers will be able to rent out the apartments through the AKA rental program. The condos at AKA Sutton Place and AKA United Nations are asking between $1 million and $3 million, with a $10 million penthouse at AKA Sutton Place.

“If you are going to be a primary resident, this is not the place for you,” said Rodrigo Niño, CEO of crowd-funding platform Prodigy Network, a partner on AKA United Nations and AKA Wall Street, which is set to open in February. But, he said, if you’re an investor “you can put the unit in AKA’s short-term rental program and then use it [yourself] at your leisure.”

Meanwhile, traditional hotels are exploring their own extended-stay models, too. The Palace Hotel, for example, offers long-term stays at its Tower Suites, where a one-bedroom is currently available for $20,000 a month and a penthouse is asking $250,000 a month. At the more value-oriented Q&A, a 132-room hotel that’s housed within Rose Associates’ 70 Pine Street (a 612-unit rental building), prices start at $212 a night for a studio and $1,104 a night for a two-bedroom suite. Furnished Quarters is the hotel operator.

In addition to its joint venture with Korman and AKA, Prodigy is developing three residential buildings that will combine short-term rentals and co-working space. This spring, Prodigy paid $121 million for 331 Park Avenue South and 114 East 25th Street, which will have 141 apartments combined. Prodigy’s 17 John Street will have 185 units. “Seventy-five percent of the people who come to the collaborative work spaces are from out of town,” Niño said. “And normally you lose them to nearby hotels.”