Churchill Real Estate Holdings’ Justin Ehrlich made a name for himself as a New York developer snapping up distressed Downtown buildings during the financial crisis and turning them into luxury condos.

But lately, his focus has been on another high-growth business: cannabis.

In addition to his property dealings, Ehrlich is a partner in Loudpack, an umbrella company of brands that sells a popular line of vaporizers, among other products. He’s also a partner in Greenwolf LA — a recreational marijuana shop in West Hollywood described as “the Whole Foods of dispensaries” — and has a stake in the ne plus ultra of stoner culture: High Times magazine.

While the burgeoning cannabis business may seem contrary to New York real estate, Ehrlich said the two have more in common than one might think.

“It’s the same philosophy as when we were buying up distressed properties,” he said, referring back to the recession. “There was a lot of fear in the market, and we knew whoever had cash on hand was going to clean up. It’s the same thing we’re doing now [with cannabis products]. A lot of people don’t want to touch it because it’s very risky and it’s a lot of work.”

Ehrlich is one of several real estate players looking to get in on the ground floor of an industry with a vertical growth trajectory.

As states around the country loosen restrictions on marijuana for medicinal and recreational uses, there’s a growing class of investors clamoring for a piece of what the cannabis research firm Arcview projects to be a $57 billion industry worldwide by 2027. New York, Illinois and Florida are among the states now looking to legalize marijuana for recreational use, and doing so would not only give them a major tax revenue boost — it could also pump billions of dollars into real estate leasing, sales and financing deals.

And a number of property investors are looking to capitalize on the increasing need for cannabis-friendly commercial space by launching specialized funds and real estate investment trusts. To date, there are around 10 REITs and private funds exclusively focused on the marijuana industry.

“The investor class in cannabis is similar to any other investment today,” said Adam Levin, whose private equity firm Oreva Capital bought a majority stake in High Times in 2017. The magazine’s owners are now pushing for an initial public offering at a valuation of about $225 million. “People who invest in real estate,” Levin added, “there’s just all this overlap because of the opportunities cannabis investments present today.”

The roster of big-time players in the sector is also growing.

The roster of big-time players in the sector is also growing.

Money managers BlackRock and the Vanguard Group are the biggest investors in Innovative Industrial Properties, the top-performing cannabis REIT. We Company CEO Adam Neumann is an investor in an Israeli medical marijuana company. Magnum Real Estate Group principals Ben Shaoul and Marc Ravner are partners in Ehrlich’s growing cannabis empire. And the blue-blooded Durst family even teamed up with the Greater New York Hospital Association in 2015 in a bid for one of the state’s first medical growing licenses— though the duo lost out to five other ventures including Columbia Care, which now runs a dispensary in the East Village.

“We were interested in that because we have one of New York’s largest organic farms,” the Durst Organization’s spokesperson, Jordan Barowitz, told The Real Deal. “As a real estate company, we are familiar with highly regulated industries.”

Into the weed

In total, 33 states have now legalized medical use, while 10 states (plus Washington, D.C.) have made recreational use legal. These early adopters have handed New York, Illinois, Florida and others a roadmap for what worked and what went wrong.

But the latest states are far behind places like California, Colorado and Nevada, where recreational use is already legal and the cannabis industry is in growth mode, sources say.

“I think Nevada has probably done it best,” said Michelle Bodner of the medical marijuana company Curaleaf New York, which holds one of just 10 medical licenses in the Empire State. “They started their adult-use program very slowly and were very cognizant of oversupply problems.”

New York, meanwhile, has shelved plans to legalize recreational use in its latest state budget, and New Jersey lawmakers recently voted down a similar proposal.

How the U.S. cannabis market and cottage industries around it evolve largely depends on federal and state regulations. Too many restraints could stifle a potentially booming industry, while sweeping legalization could fuel an investor frenzy across state borders, pushing out local players, experts say. For now, as long as federal laws prohibit the cultivation or sale of marijuana, it’s a divided market.

“This is generating revenue for the states, and [state governments] may be covetous of that revenue,” said John Massocca, a stock analyst at Ladenburg Thalmann Financial who covers Innovative Industrial.

Marc Spector, principal of the New York design firm Spector Group, which works with cannabis clients, said those heavily invested in the business are eager for federal changes that would allow money to flow across state lines. “Right now, on a state-by-state basis, you are siloed with what you can do,” he said. “A growing company can’t use resources from Colorado to expand into New York.”

And while real estate is essential to the marijuana industry, there are huge barriers to entry. On top of federal restrictions, the business still conjures up images of smoke-filled dorm rooms and streetcorner drug deals for some. Many banks and other large corporations won’t go near it. The same goes for most of the big commercial brokerages, at least publicly, sources say. CBRE, JLL and Cushman & Wakefield, for example, have published only a handful of detailed reports on cannabis and real estate. At the same time, property owners are still working out the legal kinks of renting space to tenants that create or sell marijuana products.

New York attorney Jerry Goldman, co-chair of Anderson Kill’s regulated products practice, said that while landlords have been charging less of a premium on rents for dispensaries as legalization becomes more mainstream, the costs are still generally higher than in leases for other businesses. That’s largely due to uncertainty over how federal marijuana laws will be enforced on the local level, he noted.

Goldman referred to the federal “crack house” law — which makes it a felony to knowingly lease space for the manufacturing or distribution of any controlled substance — as a deterrent to leasing space to cannabis companies.

“That risk does exist until federal law changes,” he said.

High rates

Matthew Schweber, an attorney at Feuerstein Kulick who represents dispensaries, manufacturers and other marijuana companies, called it the “cannabis premium.” Schweber said he’s representing a client who was awarded a license in West Hollywood and, for those reasons, will likely pay double the rent a noncannabis company would. “It is a legal concern,” he said, noting that landlords “will say there’s the risk of foreclosure.”

If an individual or company has a mortgage on a property and leases it to a cannabis producer, that landlord is violating a clause of the mortgage, which means the bank could demand full repayment of its loan at any moment, Schweber added. The clauses stem from federal lending guidelines, and in some cases, companies in the marijuana industry need to pay all cash to buy property for growing and distribution.

That’s left a huge void when it comes to financing for cannabis companies looking to lease or build out space, one that specialized REITs and private funds are stepping in to fill. Many of these new entrants buy properties, pay off the mortgages and then lease back to the operators, knowing they can get two or three times the typical rent in that area.

But the higher rates most of them charge — 150 to 200 percent in some cases — make it hard for smaller firms to break into the cannabis business, sources say. And that’s creating an uneven playing field in the industry.

“It’s very difficult for any company other than, say, a large multistate operator to be able to afford the cost of operating,” Schweber said, “because the real estate is as critical to their welfare as any other component of their business.”

That landscape is further kept in check by a limited number of licenses per state, which caps the number of competitive players — even in big recreational markets like Los Angeles and Denver.

In L.A., landlords still have “all the leverage in the world” over would-be tenants, said Ali Mourad, a broker at Sperry Commercial who’s worked with both cannabis tenants and landlords.

The city is expected to allow another 200 licenses over the next few years, but the process can be complicated and expensive, Mourad said. Cannabis companies have to secure a lease before they can get a license, which makes it even harder for property owners to commit to lease agreements.

The city is expected to allow another 200 licenses over the next few years, but the process can be complicated and expensive, Mourad said. Cannabis companies have to secure a lease before they can get a license, which makes it even harder for property owners to commit to lease agreements.

“It’s still really complicated, and that’s caused confusion on the landlord side,” Mourad said. “And there’s still a stigma there. Then you have zoning restrictions, so operators are really limited to where they can go.”

Limited supply

Where there’s resistance, however, there’s also opportunity, as shown by the investors and lenders that have pounced on the burgeoning business.

The publicly traded Canadian cannabis firm Harvest Health & Recreation partnered with two family offices late last year to form a $100 million real estate fund called Aina We Would, for example. Harvest, which spun off its property holdings, will finance acquisitions and new construction projects while pursuing its own investments through the fund, including land purchases and sale-and-leaseback deals.

Aina We Would lends to other companies at an interest rate of about 12 percent, which accounts for the legal risks it takes on, said Harvest Health President Steve Gutterman. He argued that it’s a good price, citing a going rate closer to 16 percent.

A number of similar funds and REITs have cropped up in California.

Inception Companies, a private investment firm based in Beverly Hills, launched a $50 million cannabis REIT last August. Inception is also focusing on leaseback deals with marijuana companies. And the popular L.A.-based retailer MedMen Enterprises partnered with the family office Stable Road Capital in January to form a cannabis REIT called Treehouse. Similar to Harvest, Medmen spun off its real estate assets in a deal valued at about $100 million, financed in part by Treehouse’s first capital raise of $133 million.

While there are several risks to investing in cannabis-related property, the financial upsides can be significant.

San Diego-based Innovative Industrial, which specializes in medical-use marijuana farms, was the country’s best-performing REIT in 2018, netting investors a 117 percent profit — beating out Vornado Realty Trust, SL Green and other large traditional real estate players.

Massocca of Ladenburg Thalmann said companies focused on triple-net lease deals pay cap rates in the single digits for less desirable real estate, like properties leased to tenants with bad credit. Innovative Industrial, on the other hand, is investing at cap rates in the low to mid teens, which means there’s plenty of room for it to improve a property’s fundamentals, he noted. The REIT’s performance “has risen dramatically” in the past few months, Massocca added.

At the same time, the field of financiers in the pot and real estate arena is still narrow, said Dan Leimel, CEO of the private real estate investment firm Pelorus Equity Group. The company, based in Newport Beach, California, launched its own $100 million debt and equity fund targeting cannabis-related real estate in September.

“It’s not a robust market in a sense that there’s a lot of players,” Leimel said. “Is it robust for those of us in it? Yeah.”

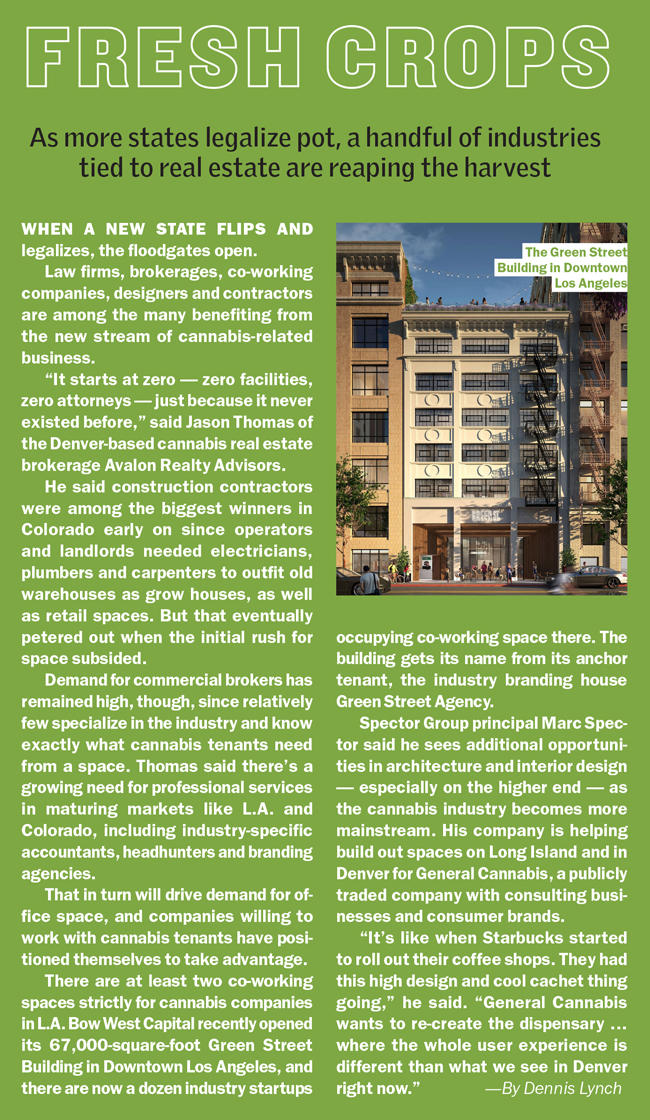

MedMen’s dispensary storefront at Ashkenazy Acquisition’s 433 Fifth Avenue

Jason Thomas, founder of the Denver-based cannabis real estate brokerage Avalon Realty Advisors, said there were “less than 10 large-cap” players, but estimated there were several hundred smaller investors with somewhere between $3 million and $5 million to deploy. Many are one-off investors working in local markets, he said.

But as more states legalize, REITs and private funds are jockeying to establish themselves in those markets. And the industry could be in for a major shift if the federal government lifts financing restrictions and institutional lenders flood the market.

The New York Times reported last month that nearly all of the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates favor legalization and have framed it as a racial justice issue, since nonwhite offenders are disproportionality imprisoned over marijuana offenses. Meanwhile, President Donald Trump has sent mixed signals on the issue but has said that he would back a bill protecting cannabis businesses with state licenses, the paper reported.

Leimel said increased competition pushes him to sharpen his business model. He argued that his firm will thrive on value-add deals, especially in cases where banks may only lend a portion of what operators need to build out a space or expand operations.

If and when “federal restrictions are lifted, we’re going to beat banks all day on that,” Leimel said.

A tighter lid

MedMen opened its first Manhattan dispensary last year — a sleek storefront at Ashkenazy Acquisition’s 433 Fifth Avenue that’s been compared to an Apple store.

Zeeshan Hyder, MedMen’s chief corporate development officer, said the posh location was very intentional. “Our retail strategy includes being a first mover in attractive consumer markets,” he told TRD by email, noting that the Fifth Avenue lease deal “is an extension of the playbook we’ve executed on in California.”

Hyder cited the regulatory and legal environment, including zoning laws, as the biggest challenge his company faces in New York.

And those invested in the cannabis industry in New York could face even more hurdles if the state legalizes recreational use. Curaleaf’s Bodner said that when it comes to selling marijuana even for medical use, “New York is the most highly regulated state in the country.”

New York’s limited number of licenses allow those companies to operate a total of 40 medical dispensaries in the state of nearly 20 million residents, Bodner noted.

Florida, by comparison, has seven times the number of dispensaries per capita, while California authorities have issued over 10,000 commercial cannabis licenses to businesses in the state and has 49 active medical licenses.

New York City could be further hampered by density issues. Of the 10 companies licensed to grow and dispense marijuana in the state in 2019, for example, none are growing in the five boroughs. The closest ones are more than an hour north of the city in Orange County, and one operation grows in Monroe County near Lake Ontario.

But while the number of dispensaries in New York remains capped, that’s led to better quality control. “We have the best product in the country,” Bodner said about the consistency of the state’s medical marijuana — including its potency.

“You look around at other states where licenses have been issued to people who perhaps don’t have the background of professional growers, and the market becomes flooded and prices implode,” she added. “Things go to the black market.”

It remains to be seen how and when New York lawmakers will address legalization for recreational use. For months, it looked as though Albany would deal with legalization in the state budget process, wrapping on April 1. But in late March, Gov. Andrew Cuomo said the prospect of getting legalization done through the budget process was unlikely, signaling that it may get picked up later this year in the legislative session.

By comparison, in the two years after Colorado legalized pot for recreational use, grow house leases in metro Denver rose two to three times higher than average warehouse rents in top cultivation submarkets, according to CBRE. And industrial buildings occupied by cannabis companies in that market saw their sales prices rise more than 17 percent between 2014 and 2017, from $98 to $115 per square foot.

Denver’s City Council did not cap dispensaries and grow operations until April 2016, which slowed what was until then strong demand for space and likely tempered rent growth, sources say.

In California, which legalized recreational marijuana just last year, the values of state-compliant properties in the Los Angeles area have risen by as much as 50 percent, Pelorus’ Leimel said. That growth has been strongest with industrial buildings in blighted desert areas in northern L.A. County, he noted. Property values increase not only due to the higher rents, but also because some cannabis companies are investing millions to accommodate large-scale growth operations.

“These are high-tech spaces,” Leimel said. “Some of them look like hospitals.”

Similar strains

The picture in Illinois is similar to New York, with most of the growth operations taking place far outside the city.

Tim McGraw, CEO of the California-based development and property management firm Canna-Hub, said that on top of the high costs in both markets, “there’s typically more bureaucracy in a big city.”

“Why would you want to deal with it?” he asked.

Still, some investors are ready to dive head first into New York.

Leimel said his fund has been closely tracking the state’s cannabis market and political environment — and he suspects others are doing the same.

If New York legalizes recreational use, many think the landscape will look a lot different than it does on the West Coast. Avalon’s Thomas said the volume of licensing will play a big part in how real estate is impacted.

“A state that has a shallow pool of licenses that will likely go to the most qualified applicants is not going to perpetuate a massive green rush for properties,” he noted, “because maybe we’re talking about a dozen stores and the same amount of cultivation locations.”

Brian Staffa, founder of the New Jersey cannabis consulting firm BSC Group, said East Coast states have kept a tighter cap on licenses overall.

How and where a state distributes its licenses is also important, he added. A state like New York would be wise to allow more cultivation licenses in rural areas and more retail locations in the city, Staffa said. That could revitalize areas with obsolete and disused industrial space.

But he cautioned that there may be just a few winners in New York real estate when all is said and done. Staffa said it’s important that developers and property owners carefully analyze demand before building too big.

“Mistake No. 1 is misreading the potential market to drive project size,” he said, noting that some developers in legal states “have built out at such a scale in markets that couldn’t support it and they just bled and bled.”

—Additional reporting by Eddie Small in New York and Joe Ward in Chicago