Multifamily projects have been on the rise across Westchester and Fairfield counties for a while, so much so that sometimes it seems like it’s all anyone can talk about when it comes to suburban real estate.

But experts say there’s been a slowdown in construction loans from traditional lenders for these developments in both counties, citing concerns about too much multifamily stock in some markets despite continued strong demand and high occupancy levels.

“The market slowdown started maybe at the beginning of 2016, where lenders were more concerned with saturation in markets that have seen a substantial amount of multifamily growth,” said Mark Fisher, senior vice president at CBRE. “Loan values and loan-to-cost [ratios] have dropped also. Banks that were willing to make 75 percent [recourse] loans are down to 60 percent.”

Stamford is one area that has seen a significant amount of rental property growth, with about 15,000 units being added or in the pipeline over the past 10 years, said Thomas Madden, director of economic development for the city. The population has grown “from 122,000 in 2010 to just shy of 130,000 today,” he added.

Just over 3,600 units were under construction or approved as of the first quarter in 2017; however, multifamily permits dropped 31.6 percent from a year earlier, from 38 to 24.

Still, demand and absorption remain strong. The occupancy rate for Stamford is above 96 percent, said Madden, with a new 200-unit building being leased up in eight months as opposed to the norm of 36 months.

But as with any cycle, it’s hard to predict when it is at its peak. “There are a couple of factors,” said Wilson Kimball, commissioner of planning and development for Yonkers, which has about 1,000 units under construction and 2,000 approved. “The stock market is really high, and the recovery window from 2008 is now at nine years. Real estate cycles tend to be eight years. So you wonder. And no one knows what fiscal impact the federal tax bill is going to have. You’ll find more people being more risk-averse and more conservative.”

But as with any cycle, it’s hard to predict when it is at its peak. “There are a couple of factors,” said Wilson Kimball, commissioner of planning and development for Yonkers, which has about 1,000 units under construction and 2,000 approved. “The stock market is really high, and the recovery window from 2008 is now at nine years. Real estate cycles tend to be eight years. So you wonder. And no one knows what fiscal impact the federal tax bill is going to have. You’ll find more people being more risk-averse and more conservative.”

Peak rent

Another concern lenders have is that rents have leveled off, and landlords are increasingly having to sweeten lease terms with incentives.

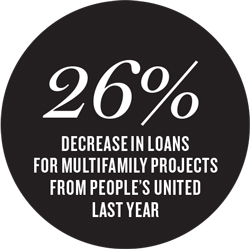

“In certain markets, we see one, two or three months’ rent [offered] to new tenants,” said Marjan Murray, executive vice president for commercial real estate lending at People’s United. The bank is the leader in multifamily construction loans for lenders based in Fairfield County, but it reduced the amount of these loans by 26 percent from September 2016 to September 2017, according to FDIC data.

Median rent for one-bedroom apartments in Westchester peaked in April 2016, at $2,289, according to Zillow. As of October 31, it was $2,257. Fairfield’s one-bedroom median rent hit a high in October 2016 of $1,907. A year later it was down to $1,708.

This doesn’t, though, take into account the varied locations and quality of product on the market in each county. “We still do deals in the right locations, for the right sponsor and with the right loan structure,” Murray said.

Successful plans

What makes for a solid project that will likely get financed? Experts say it’s proximity to a commuter train station with easy access to New York, high-end finishes, luxury amenities and walkability to a thriving downtown area with plenty of restaurants, bars and shops.

“[Developments where] people won’t have to get in their cars and drive three miles to go to the store,” said Matthew Bissonette, director of Citi Community Capital, which specializes in financing developments that have an affordable-housing component.

Lenders are leery about retail. “You have to be very careful,” said Mike Riccio, senior managing director at CBRE. “It has to be a small part of the income, because most lenders won’t give you credit for it, or will give very little for it.”

If the project does include retail, it’s best to keep it to the first and second floors, and developments should focus on tenants with experiential-type businesses as big-box stores are no longer a safe bet, experts said.

It also helps, of course, to have a successful track record and established relationship with a lender. “The key to these deals are borrowers who have great relationships with lenders and have done previous deals and executed them successfully,” said Steven Rock, first vice president, capital markets, for Marcus & Millichap Capital Corporation. “If you’re a brand-new developer and have never done anything before, it’s very challenging to get attractive financing terms.”

It also helps, of course, to have a successful track record and established relationship with a lender. “The key to these deals are borrowers who have great relationships with lenders and have done previous deals and executed them successfully,” said Steven Rock, first vice president, capital markets, for Marcus & Millichap Capital Corporation. “If you’re a brand-new developer and have never done anything before, it’s very challenging to get attractive financing terms.”

Alternative lenders

Traditional lenders provide about 95 percent of construction loans, CBRE’s Riccio said, and many of these banks will only work with their very best customers. But alternative lenders are moving into the market to fill the gap.

“Debt funds saw a new opportunity when the banks pulled back,” Riccio said. “For some developers, it’s their only option.”

Marcus & Millichap’s Rock started seeing a lot more of these lenders in the space about a year ago. They are willing to take on riskier projects that banks won’t do — for a price. Not surprisingly, the terms for these loans are less attractive than what traditional lenders typically offer. The interest rates will be higher, and there could be more recourse.

“They lend at a lower loan-to-cost ratio, but more equity is required in their deals,” said Mike Maturo, president of RXR Realty, which has several multifamily developments in Westchester and was chosen to be the master developer in New Rochelle (see page 18).

Alternative lenders don’t have to adhere to regulatory restrictions that banks do, added Maturo, like the Basel III regulations that went into effect in January 2015. Those rules introduced new capital and liquidity standards to strengthen the regulation, supervision and risk management of the banking and finance sector.

One such area of the regulations is HVCRE, or high-volatility commercial real estate, where developers who want a construction loan from a bank need to contribute at least 15 percent of a project’s value in cash. If they don’t, the bank must set aside a larger amount of capital to insulate itself against losses. These regulations are limited to larger loans, usually over $100 million.

One of the biggest differences between traditional and alternative lenders is that for construction loans, banks will count the book value of a land asset that could have appreciated greatly over time, not the current value.

“If you bought land 50 years ago and it’s worth more today, you cannot get credit for that increase,” said CBRE’s Fisher. “That makes it almost impossible on legacy properties unless you have an inordinate amount of equity in the deal.”

But alternative lenders will give you credit for the current value. “That makes a big difference,” said Maturo.

Insurance companies are another type of nontraditional lender, although they don’t typically do too many multifamily projects. “They’re very specific in what they want,” said Riccio. “They’ll fix the rate through the construction period and give a 10- to 12-year loan. It’s not the cheapest way to finance construction, but if you’re looking for long-term and you’re not sure where interest rates are going, it’s a great alternative.”

The land issue

The biggest challenge — for both market-rate and affordable housing developments, which are in high demand — is land costs. The high premium on space in the area, not to mention the construction costs, gives many lenders pause when they are deciding about financing a project. In addition, projects with restricted income must compete with market-rate properties, where developers can “charge three times as much,” said Citi’s Bissonette. But even developers with more capital can have a hard time finding the right parcel.

“A lot of suburban communities are not zoned for multifamily. Zoning changes have to happen,” said Heidi DeWyngaert, chief lending officer for Bankwell Financial Group. “Approval and zoning are barriers to entry by developers who see an opportunity, so towns have to come to an understanding that it’s something they want and be open to changing zoning.”

Darien went through that in early 2017 during an approval process for Baywater Properties’ downtown development. In Westchester, Yonkers and New Rochelle have addressed these issues and made project approvals easier to obtain.

Construction costs are also high in the region, which can make obtaining lending more difficult. “It’s hard to make the numbers work without some government support,” said Tim Jones, vice president of the board and vice chair of economic development for the Business Council of Westchester and CEO of the Robert Martin Company. “The numbers end up being tight, especially with high-rises … Costs go up a lot when you go over five stories.”

Some lenders will work with developers to try to make a project come to fruition.

“There are times when we’re approached by a developer with limited capital, and we may leverage another asset or property in addition to the construction property to make it work,” said Anthony Pili, vice president of strategic planning for Greater Hudson Bank, which lends in both Westchester and Fairfield. “We’ll also look at government programs and counsel them on what might be appropriate for them.”

Future opportunities

Despite the uncertainty, many remain bullish on the market and there continues to be high demand for multifamily construction loans in both Westchester and Fairfield.

“We haven’t seen a problem with absorption yet,” said Marsha Gordon, president and CEO of the Business Council of Westchester. “There’s still a lot of units to come on, but my guess is there is a lot of potential market as well. You have to look at the overall New York market, and our pricing is still below Jersey City, Manhattan and Brooklyn.”

There’s also been pent-up demand — some of the towns in the counties haven’t seen new multifamily developments in 50 years, added CBRE’s Riccio. “We haven’t overbuilt. People really want to rent in new apartments with new amenities. They’re moving out of the old stock and into the new.”

In both counties, growth continues along the transit corridor. For Fairfield, experts said interest remains strong in Stamford, Norwalk, Darien, Westport, Danbury and the town of Fairfield. There’s also strong demand for Greenwich, but not much to choose from as there aren’t many parcels of land available, said Marcus & Millichap’s Rock.

In Westchester, White Plains has a lot of projects on the drawing board that have yet to finish the permit process, but it’s where developers and lenders see continued demand. In addition to Yonkers and New Rochelle, developers are also keen on Mount Vernon and Port Chester, the latter of which recently opened a request for proposals for a master developer for its downtown area. Tarrytown, Hastings-on-Hudson and Ossining are also getting interest from multifamily developers.