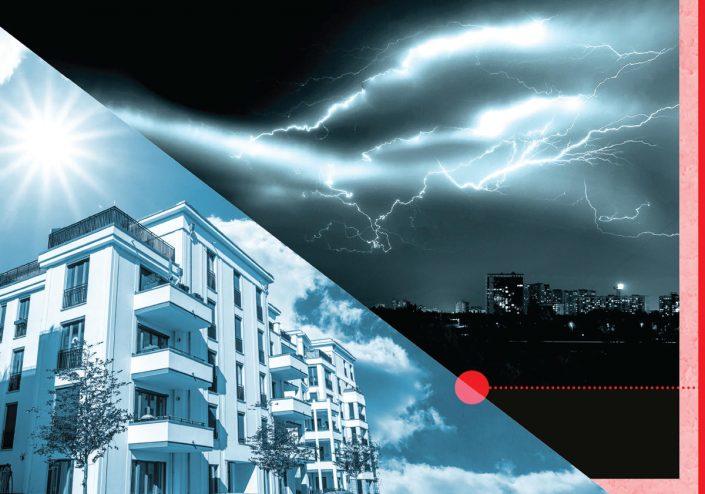

While hotels, retail and offices sink, the multifamily sector is sailing along.

While hotels, retail and offices sink, the multifamily sector is sailing along.

Rent collection has been largely steady despite high unemployment and early threats of rent strikes. Occupancy, too, has suffered less than expected except in dense areas and at the high end of the market, where tenants were more likely to relocate to a second home and new leases dwindled.

Commercial properties have lost revenue to lockdowns, reduced travel and online shopping, but people are using their residences more than ever. That has benefited the sector.

“For multifamily, these are peoples’ homes, and for many it’s become the place to work as well,” said Marc Wieder, co-leader of the real estate group at accounting firm Anchin. “It’s become even more important than before.”

Multifamily assets have not yet seen widespread distress. Firms whose portfolios are short on multifamily are looking to acquire more, and some are pondering converting nonperforming assets to apartments.

There really isn’t any distress to speak of in the multifamily market. But any owner would be lying if he said income hasn’t gone down.

Still, multifamily profits have diminished, and the sector would not be immune to a long recession. A U.S. Census survey found 15 percent of tenants were not current on rent in October. Eviction moratoriums and the prospect of rent control loom. Some owners are impatient with moratoriums, arguing that the possibility of eviction is necessary to get some tenants to pay.

“There really isn’t any distress to speak of in the multifamily market,” said Stuart Boesky, chief executive officer of New York-based investment firm Pembrook Capital Management. “But any owner would be lying if he said [net operating income] hasn’t gone down.”

Collections stable for now

The memory of federal stimulus checks has faded, and the $600-a-week federal unemployment supplement ended in July. Rent collection, however, has not fallen much, a survey of 11.5 million market-rate apartments shows.

Jeffrey Levine, chair of Douglaston Development, said that in his affordable portfolio, rent collection is about 80 percent and occupancy is in the high 90s. In units covered by Section 8, a federal subsidy, occupancy and collection have not dropped at all, because of steady checks from the government.

Not all apartment owners are faring so well, however.

Daniel Goldstein, managing partner of E&M Management, a New York City owner that in recent years has become the Hudson Valley’s largest landlord, said rent collection in the firm’s portfolio has dwindled to 65 percent of normal. It was better early in the pandemic, he said, when tenants were receiving enhanced unemployment benefits.

Still, Goldstein said he is thankful to not be an office landlord. In fact, his firm is in contract to purchase two office towers outside of the city to convert into apartments.

New York-based Gaia Real Estate, led by Chief Executive Officer Danny Fishman, is pursuing a similar strategy. His firm is considering converting hotels in New York City to residential, but he declined to share details.

Although rent rolls have not suffered the losses predicted in the spring, many landlords are troubled by the prospect of extended eviction bans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention implemented one in September. Some states and cities have more stringent bans. Many in the industry expect the moratoriums to endure, given surging infections.

If there is a feeling of possibly being evicted, instead of buying a 40-inch TV, tenants pay the rent. Not having that feeling is causing a lot of problems.

“If things go along the way they have been, or possibly worse, there is a good chance the eviction moratorium will be extended,” said Wieder, the accounting firm executive. “It is imperative that the government look out for people in their homes, because they will become a burden to the government if they are evicted.”

Wieder also lamented the lack of government assistance for landlords, who were ostensibly shut out of the Paycheck Protection Program — although a number of landlords and developers were able to tap into it through loopholes and affiliated entities.

Even as some industry professionals acknowledge that evictions are problematic during a health crisis, others say some tenants are exploiting the protections unfairly.

One large New York City property owner, speaking on condition of anonymity, expressed hope that Gov. Andrew Cuomo would lift the eviction limits in New York for “those who are taking advantage of the pandemic by using it as an excuse to not pay rent, despite their ability to do so, or abide by the nuisance terms of their lease.”

Goldstein put it more bluntly: The threat of eviction compels tenants to pay rent, he said, and without it, some tenants choose not to.

“If there is a feeling of possibly being evicted, instead of buying a 40-inch TV, tenants pay the rent,” Goldstein said. “Not having that feeling is causing a lot of problems.”

Beyond Covid

The problems that do exist in the multifamily market were brewing long before Covid.

In New York City, a spate of tenant-friendly regulations passed last year, and subsequent electoral gains from tenant-backed politicians pushing more rent regulation will be a driver of distress in the multifamily market, said Boesky.

“The biggest problem New York has is the new rent regulations that came into existence last year,” the investment manager said. “That’s a bigger issue [for multifamily] than the coronavirus.”

Investors are concerned that rent regulations will be expanded to new development — although legislation to do so has made little progress — and are less willing to assume that risk, Boesky explained.

“There is a huge chilling effect caused by the rent regulations, even though they don’t apply to new development,” said Boesky. “Why would you take the risk until you know for certain it will blow over?”

At the same time, industry forces prevailed in California with the defeat on Election Day of two ballot measures viewed unfavorably by real estate. Proposition 15 would have raised taxes on commercial real estate owners, and Proposition 21 would have allowed localities to expand rent control. The real estate industry spent more than $100 million on opposition campaigns.

The changes in New York, which some say eroded multifamily asset values 25 to 30 percent, have not yet resulted in widespread fire sales. Among those whose equity was wiped out by the new law, few are ready to sell at prices low enough to entice buyers.

“Eventually, there will be an opportunity to purchase those [assets] at cap rates that make sense,” said Levine, referring to buildings purchased with rent-hike expectations that were dashed by the new law.

Laurent Morali, president of Kushner Companies, explained that it may take some time for the rent-regulated market to stabilize.

“If you’re going to buy something today [in New York City] it takes a bit of courage — you don’t want to be an investor buying something and then six months later look like a fool because a much bigger trade takes place at a much lower price,” he said.

Even in the city, where the vast majority of the state’s rent-stabilized portfolios are, only those overleveraged will be at risk of default. It’s unclear what fraction of the market that could be, and lenders, rather than take back the keys, might prefer to let borrowers restructure their debt.

New York’s rent law reform stemmed from a progressive turn in the state’s politics. Yet some multifamily owners see signs that, despite more wins by far-left candidates this year, state politics are moderating.

In the November election, some Democrats hoped to secure a veto-proof majority in the state Senate — allowing them to pass more progressive legislation — but the Election Day ballot count suggests they might lose a seat or two. With a more evenly divided statehouse, many expect Cuomo to push for more moderate legislation.

One large property owner, speaking on condition of anonymity, was encouraged by the federal and state elections but worried about next year’s mayoral and Council races.

“We are looking toward next year’s New York City elections with the hope of a city government interested in governing for all New Yorkers and those looking to move to New York, not merely implementing unsustainable policies that meet the demands of tenant advocates or socialist politicians,” the owner said.

“The stability of New York’s housing is on the edge of a precipice and requires pragmatic leadership to secure it.”