In the fall of 2015, Bob Knakal was watching the bids come in for Manhattan land parcels across a portfolio of 40 sites.

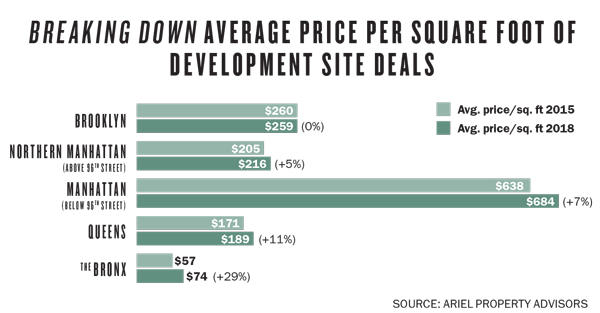

They weren’t good. Coming off a two year-boom in the market for development sites, buyers had been consistently bidding an average of $685 per square foot for Manhattan dirt. Almost overnight, those offers began plummeting by around 20 percent.

Then the chair of Cushman & Wakefield’s New York investment sales team, Knakal turned to his partner John Hageman and said: “It’s over.”

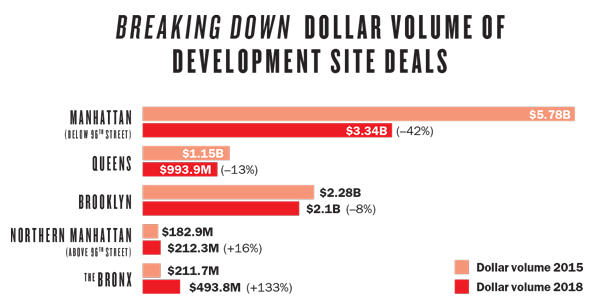

He was right. The following year, in 2016, the total dollar volume for development site trades in Manhattan below 96th Street plummeted 55 percent to $2.6 billion from $5.8 billion. In 2017, the dollar volume dropped by another 34 percent, according to data provided by commercial brokerage Ariel Property Advisors.

“That was a huge, huge air bubble,” Knakal, who in September jumped to JLL to become its chair of New York investment sales, told The Real Deal last month. “That is what’s driving price today.”

Although land sale prices did recover last year and are now roughly back to 2015 levels, the number of transactions is still significantly down.

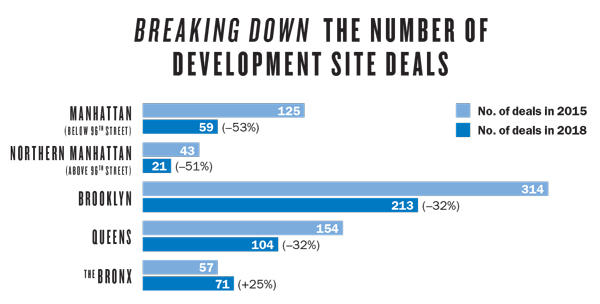

In 2015, 125 land parcels traded in Manhattan below 96th Street. In 2018, that figure stood at 59. That’s a 53 percent drop.

Citywide — or at least in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx — the picture is slightly better, but not by much.

While the pipeline of condo and rental inventory may be bursting at the seams, a dearth of land transactions now could have significant implications for the development pipeline going forward.

“There’s a lot of developers who have gone in and bought at too high a price, thinking they would build condos, and then the condo market got soft,” said Andy Gerringer, the head of new business development at the Marketing Directors, a development advisory firm. “And you are never going to make a rental work at $685 a square foot.”

In addition to high land prices and a soft condo market, developers have pulled back on buying land for myriad other reasons, including rising interest rates, the loss of 421a tax abatements, a LIBOR rate that has skyrocketed in the last three years and increasing construction costs (partly due to tariffs on steel imposed by the Trump administration), according to Aaron Appel, JLL’s vice chair and head of capital markets debt and equity.

“All those factors have a negative impact on value,” said Appel, adding that while condos have been the “highest and best use” for new development, the dynamics have changed given the oversupply of inventory.

That glut is largely thanks to the free-for-all environment that developers have been enjoying for the past decade, boosted by “enormous amounts of money available” from nonbank lending, said Andy Singer, chairman and CEO of the Singer & Bassuk Organization, the debt brokerage. “I’m not sure any land deal makes sense unless you want to drink the Kool-Aid on what [condo] prices are going to be tomorrow,” Singer said.

The pullback

Despite the cliff drop in land deals, there were several large trades last year that skewed the total dollar volume of deals.

The largest land transaction last year was Walt Disney Company’s $650 million purchase of 4 Hudson Square — a 1.2 million-square-foot site — from Trinity Church Real Estate.

Farther south, Milstein Properties finally unloaded 250 Water Street in Lower Manhattan, a parking lot with 290,000 buildable square feet.

The firm bought the site in 1979 for $5.8 million but battled with the city and community about development plans over the decades and was also facing a downzoning on the site. Instead of giving it another go, it sold to Howard Hughes Corporation in June for $180 million. The deal penciled out to $620 a square foot.

But those deals were the exception. They helped to push dollar volume of development site trades in Manhattan up to $3.34 billion last year below 96th Street from $1.7 billion in 2017, according to Ariel. That was, however, still 42 percent below 2015’s number.

“It wasn’t a secret that 2015 was a peak year for land in general, especially high-end land,” said Shimon Shkury, Ariel’s president and founder.

Shkury predicted that while the outer boroughs will benefit from zoning changes and Opportunity Zones, Manhattan below 96th Street will “continue to see transaction levels at 2018 levels.”

Across the bridge in Brooklyn, the number of transactions fell by 32 percent between 2015 and 2018 to 213 deals from 314, according to Ariel.

But remarkably, overall land sales in the borough came to $2.1 billion — only an 8 percent drop from 2015.

The picture looks less promising when zeroing in on residential deals.

According to Dan Marks, a partner at the Brooklyn-based brokerage TerraCRG, in 2015 there were about $2.1 billion in residential land site deals — a number that dropped to $1 billion in 2017 and remained there in 2018.

“Bidders are not quite at levels that sellers are trying to transact, because there’s a lot of distress in the market,” Marks said. “So buyers have pulled back for a number of reasons.”

He also said he expected an uptick in development spurred by Opportunity Zones.

Overall development sales last year in the borough were bolstered by several large deals.

In Red Hook, UPS bought a group of six waterfront properties from New Jersey-based industrial landlord Sitex Group for $303 million. The site offers up to 1.2 million buildable square feet and is likely to be home to a new distribution center. The megatransaction comes amid Amazon-induced growth for warehouse and distribution space nationwide.

On the residential side, Fortis Property Group dropped $91.1 million on the purchase of a Dumbo parking lot owned by Jehovah’s Witnesses, which it plans to develop into a 26-story, 74-unit condo. The firm locked in a $92 million land-and-construction loan from Madison Realty Capital and added equity of its own.

Asked why it invested in a project in an unpredictable market where land deals are declining, Madison co-founder Josh Zegen said Dumbo is a neighborhood where ground-up developments make sense, partly because landmark and height restrictions have created an inventory scarcity.

“Dumbo’s an area with height restrictions, landmark issues,” Zegen said. “It’s allowed [Fortis] to create a product that is in more demand.”

Overall, though, an onslaught of new inventory slated for Brooklyn is adding to developers’ concerns and steering them away from large projects. In 2019 alone, the borough is expected to get hit with 1,917 condo units and a massive 14,127 rentals, according to data compiled by the Marketing Directors. In total, the borough is expected to add roughly 35,400 units by 2021.

The Bronx is the one outlier in the city. Land trades there have been booming for the last several years as developers have tried to capitalize on reasonable acquisition costs and rising residential prices. The borough saw a 25 percent increase in its number of deals between 2015 and 2018 — and a 133 percent jump in dollar volume to $493.8 million.

During that same stretch, prices for those sites jumped to $74 per buildable square foot from $57. Compared to the other three boroughs, those prices are still a significant bargain.

Good for the market?

As Gerringer of the Marketing Directors noted, developers from Upper Manhattan to the outer areas of Brooklyn are still sitting on land that they paid a steep premium for a few years ago and are contending with a soft residential market.

For the first time in three years, the median price of a Manhattan condo dropped below $1 million in the fourth quarter, according to Douglas Elliman’s latest market report. That was down more than 10 percent from the third quarter and nearly 6 percent year over year.

And construction costs in the city were the highest in the world as of May 2018, hitting an average of $362 a square foot, according to Turner & Townsend’s 2018 International Construction Market Survey. That was a 3.5 percent increase year over year, a figure that is expected to double once totals for the full year are tallied.

In addition, 421a abatements, a huge selling point that developers could pass along to buyers to make their projects more appealing, are no longer available in Manhattan. (The tax breaks are still available for some qualifying projects in the outer boroughs).

All of this is making it difficult to pencil out their projects.

Gerringer said volume is “way down” because developers can’t make condos work and don’t want to build rentals.

Knakal predicted that land prices would continue to rise this year. “Not substantially, but they will,” he said. “The truly prime sites will continue to go up at a good pace, but they have to be the best of the best.”

But until prices come down, some say, developers will be reluctant to pull the trigger on purchases.

This pause in sales is actually a good thing for the market, giving it time to absorb the oversupply of condo inventory, said Robin Schneiderman, the director of business development at Terra Development Marketing, which oversees Halstead Property Development Marketing and Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing.

“In terms of future pipeline, not this year, maybe next year, you will see [fewer] new development units come online, which will help correct the market,” said Schneiderman.

Knakal also noted that there will never be a total standstill in transactions.

“Developers are gamblers by nature,” Knakal said. “They are gambling on the fact that market conditions will be better on the land they are buying today, and will be better when they sell the end product.”