National Drive in Mill Basin, Brooklyn, is a museum of late-20th-century suburban hodgepodge: A modest colonial here, a questionable Spanish villa there. Stucco sits beside stone and brick beside vinyl.

None are so remarkable, however, as the edifice sitting where National Drive ends near the Mill Basin inlet, just off Jamaica Bay. With its white façade, black windows and wall-to-wall marble, 2458 National Drive is an acquired taste.

A buyer put up $10 million last August to purchase the 14,000-square-foot property, which Russian heiress Galina Anisimova put on the market in 2013. A month later, Ralph Herzka, the CEO of commercial real estate firm Meridian Capital Group, filed plans for a Robert A.M. Stern-designed mansion in Brooklyn’s Midwood neighborhood, assembling five lots to build a 15,000-square-foot home.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, an abundance of national articles declared the death of the so-called McMansion, as baby boomers looked to downsize and a progressive younger generation emerged, one presumably more amenable to economical accommodations.

But Census data shows that since 2011, the size of new construction homes nationally has been trending more in the direction of the Mill Basin manor than the Manhattan micro-unit. In fact, new houses built in the Northeastern U.S. between 2015 and 2017 were a median 2,400 square feet — larger than at any other time in American history. A further analysis of building permits by The Real Deal found New York City to be no exception, though the number of plus-sized homes has dipped within the past decade as downzonings and available construction sites have dwindled.

“[Demand] is definitely moving on the upside again,” said Gregory Kyroglou, a residential broker at Queens-based Modern Spaces. “People are looking for space. We’re back to that.”

Kyroglou said a close friend who recently finished construction on a 4,000-square-foot home in Whitestone, Queens, is already receiving unsolicited offers from buyers wanting to pay more than $1.2 million for the property.

In a city home to new luxury condo high-rises like 432 Park Avenue and One57 in Manhattan, the seemingly ever-present desire for more space creates opportunities for high-end home construction in the outer boroughs.

“What happened is the land became much more expensive,” explained Staten Island-based homebuilder R. Randy Lee. “If you have expensive land, you have to have an expensive house.”

Siren song of Staten Island and Queens

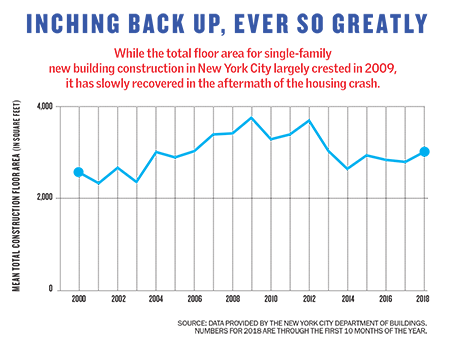

While the relatively small market for new detached homes in New York hasn’t quite brought median size back to the 2009 high of 3,111 square feet, the trend over the last year has been to go bigger, something that doesn’t surprise veteran homebuilders like Lee.

“If you read the trade magazines you will see homes getting smaller, and in many places that’s true,” he said. “[But] in the New York metropolitan area, that isn’t true. In a place like Staten Island, I would probably say it’s the opposite.”

In the first 10 months of 2018, the median space for permitted homes in the city measured 2,477 square feet, a number comparable to national figures. In Queens, however, the median of 2,974 square feet in 2017 — the most recent year for which final data is available — for 104 planned houses was the largest seen in the borough since 2012.

On Staten Island, which sees the largest volume of single-family home construction in the city and where new homes in 2017 were larger than they have been in a decade, developers have grown more cautious and overall are building fewer single-family homes, said James Prendamano, a broker at Bulls Head-based Casandra Properties on Staten Island. “There is a market for it, but it’s not what it was,” he said.

252 Benedict Road in Staten Island

In 2017, 214 houses were permitted on Staten Island with a median size of 2,454 square feet — the highest mark since 2009. But the number of homes is still less than 18 percent of what was permitted on Staten Island in 2003, during the height of the pre-crash housing boom.

Nonetheless, there is still the occasional indulgence that would give Mill Basin a run for its money. You can find many of them on Staten Island’s Todt Hill, a neighborhood located at the highest elevation in the five boroughs, where homes over 7,000 square feet abound. One mansion permitted in 2014 at 125 Circle Road measures 14,000 square feet.

Perhaps more varied in its large-home offerings is Queens, the largest of the city’s boroughs by area and the second-largest by population, and a popular place for the urban McMansion. Queens’ Flushing neighborhood has become a battleground for owners of single-story homes with small front yards to lash out at those looking to build two-story homes or those that reach all the way up to the property line.

Whitestone, an upper-middle-class area in the northernmost part of Queens where Kyroglou’s friend built large, is home to one of the last subdivision development sites in the city, an 18-acre waterfront plot with the destination-appropriate name of Waterpointe. Developers have struggled to build on the site for more than a decade, in part due to contamination that remains even after a Department of Environmental Conservation cleanup.

The latest developer to dive into Waterpointe, Chinese builder Edgestone Group, will have to outfit the 52 single-family homes it has planned for the property with “a system with alarms … to alert residents about the presence of hazardous materials to prevent them from causing health issues,” according to a Queens Chronicle report.

In more multifamily-centric boroughs like the Bronx and Brooklyn, single-family home construction is more rare and likely to be one-off infill projects, rather than planned communities of the kind Edgestone is attempting in Whitestone. City data shows that fewer than 50 new single-family homes have been permitted in the Bronx during the last five years.

In more multifamily-centric boroughs like the Bronx and Brooklyn, single-family home construction is more rare and likely to be one-off infill projects, rather than planned communities of the kind Edgestone is attempting in Whitestone. City data shows that fewer than 50 new single-family homes have been permitted in the Bronx during the last five years.

And in high-rise-heavy Manhattan, there are few places left where single-family construction can truly expand. As a result, homebuilders often resort to different ways of increasing space, such as digging into the basement, said developer Scott Hobbs, who constructs townhouses in Manhattan.

“Basements are now becoming full living spaces,” said Hobbs, noting that builders will excavate an extra couple of feet in order to make sublevel areas big enough to increase square footage.

Big footprints and shrinking price points

In a city where available space is increasingly scarce, it’s not surprising that single-family home construction has trended downwards in terms of volume since its most recent peak of 1,430 permitted homes in 2001. During the first 10 months of 2018, there were fewer than 400 single-family permitted homes.

Even so, single-family homes represented nearly 30 percent of permitted residential buildings in 2017, according to a Rent Guidelines Board report. That means such construction still accounts for a sizable amount of what is built on the city’s available land in any given year, even if it accounts for a smaller portion of the total square footage and total housing units built. (Single-family homes were less than 1 percent of the 55,000 total units of housing permitted in 2017, according to the same RGB report.)

Despite the shrinking number of new single-family homes, downzoning has helped keep them alive in some areas, including McMansion-happy Staten Island.

2458 National Drive in Mill Basin, Brooklyn

The borough’s Westerleigh neighborhood was for many years a place where two-family houses were built, but the City Council changed that a decade ago by modifying the zoning rules for 1,400 lots so that only one-family homes could be constructed. An analysis by TRD shows that at least 91 new single-family homes have been permitted in Westerleigh since 2008.

“Downzonings across the board are a problem,” said Lee, the Staten Island homebuilder. “They have eliminated the best zones to build townhouses and duplexes.”

Such restrictions can push homebuilders into the highest end of the mega-home spectrum, where softening prices can present opportunities for buyers. A 2016 Bloomberg report found that McMansion prices were falling nationwide. Hobbs said decisions made by owners who custom-built their own homes on lots in existing neighborhoods sometimes also build in the fates of those investments if they design something unattractive to most of the market.

“You can end up with more divergent architecture, because an owner can choose to do something that doesn’t necessarily make economic sense,” the homebuilder said.

2 Dover Street in Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn

That was the fate of the Mill Basin McMansion, whose $10 million sale was likely a disappointment for its former owner, Anisimova. The ex-wife of Russian oligarch and billionaire developer Vasily Anisimov and mother of Anna Anisimova — better known as the “Russian Paris Hilton” — first put her former home on the market in 2013 with an ambitious and ultimately oversized ask of $30 million.

Brooklyn-born John Rosatti, founder of the Plaza Auto Mall dealership chain and gourmet burger franchise BurgerFi, built the Mill Basin monstrosity that he sold to Anisimova for $3 million in the late 1990s. Builders of such massive homes are usually lot owners themselves and tend be from the neighborhoods where they are doing the construction, said Keller Williams broker Melissa Leifer. In Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay, Leifer said, it’s common for homegrown residents to strike it rich elsewhere and then return home to build the fanciest residence on the block.

“It’s kind of like country music stars when they make it big and they buy a 50-acre farm in Oklahoma,” she said.

Like other single-family brokers, Leifer, who specializes in the South Brooklyn submarket, has noticed the increased demand for larger homes. She added that most buyers are getting what they want not through ground-up builds, but by buying older homes and expanding them through renovations that stretch what zoning laws allow.

The community board of the Kew Gardens Hills neighborhood in Queens is in the process of asking the city to let it increase the size of homes by using a special residential zoning that only exists in two other places where large houses predominate: Far Rockaway and a slice of Midwood in Brooklyn.

“Size matters,” Leifer said. “And if the size isn’t there, you can add it.”